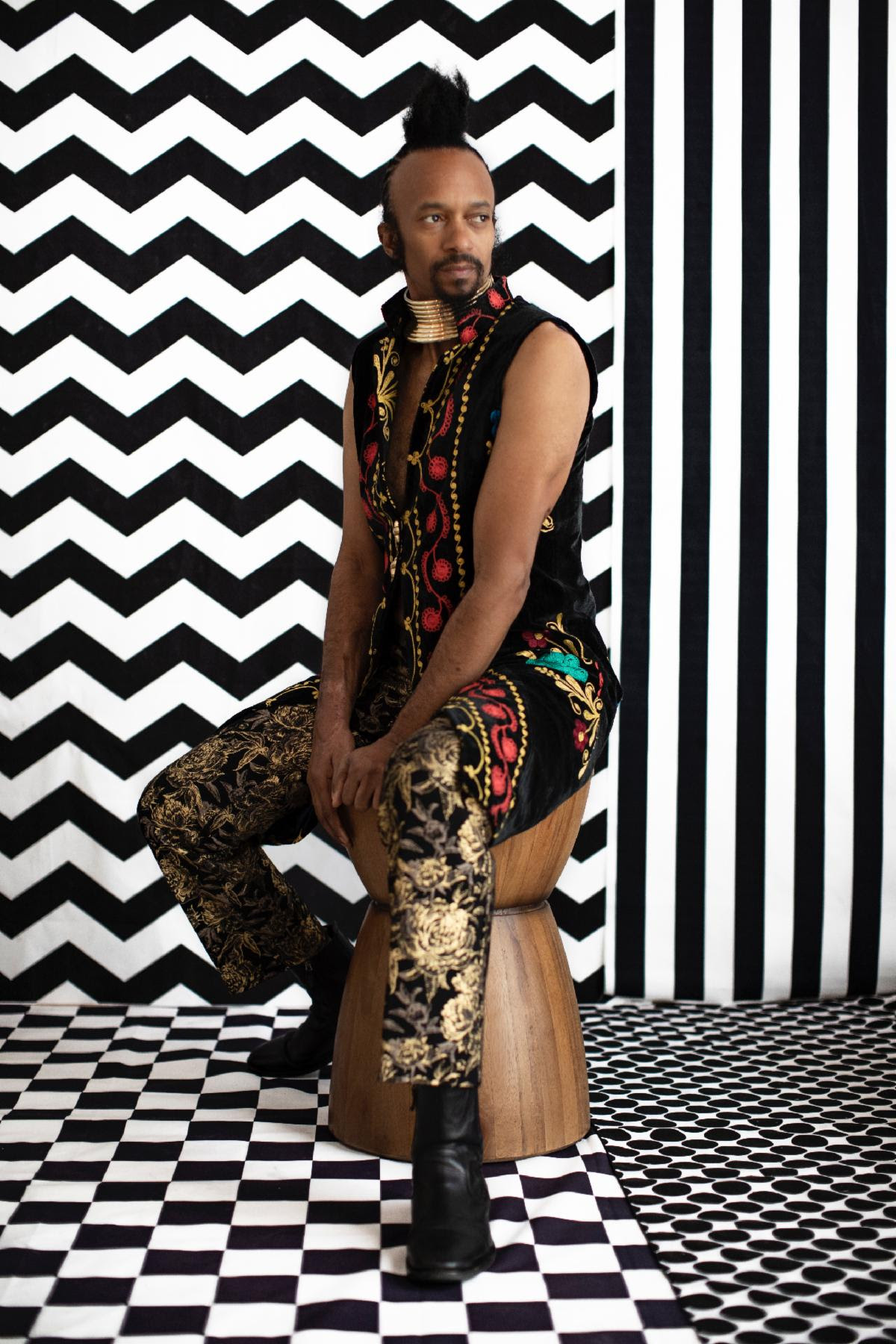

According to a 2014 study by the League of American Orchestras, less than 2% of musicians in American orchestras are African American, only 4.3% of conductors are black, and composers remain predominantly white as well. Hence, as a classically-trained cellist and person of color (POC), Ebony Miranda’s music career is in itself an act of resistance.

The classical tradition has resisted the influence of black music and perpetuated white supremacy for hundreds of years, and as one of Cornish College of the Art’s only students of color in the classical program, Miranda fought for more diversity in curricula, the student body and staff until their graduation in 2017. Years later, Miranda has also become a vocal organizer within Seattle’s official Black Lives Matter chapter, and their free improvisational solo project on electric cello, Undesirable Body, continues to explore and amplify the effects of racial oppression and the injustices faced by African Americans every day.

Ebony Miranda took some time away from supporting Seattle protesters on the front lines to speak with Playing Seattle about how music can be used as a tool in the fight against racism, their thoughts on the music industry’s blackout on Tuesday, and how allies in the music industry can step up to better support musicians of color in Seattle and beyond.

AF: Tell me about your background and how you go into music. Are you from Seattle?

EM: No, actually, I’m originally from Southern California. I moved up to Seattle seven years ago to attend Cornish. I started playing cello down there, went to a music/arts high school and decided to pursue music for school. I came to Cornish seven years ago, graduated with my degree in music, specifically classical music.

While I was studying classical music I had opportunities to do jazz band and that’s when I got more involved in free improv, in particular. Which is sort of what really set the stage for the music I do now. I never thought I’d be doing any type of improvised music but now it’s almost exclusively what I do and my solo project Undesirable Body is exclusively improv-based.

AF: And you decided to stay in Seattle. Did you feel you had enough of a community here? What prompted you to stay?

EM: Definitely, from a music point of view, yes. I was able to develop a lot of really great connections at my time at Cornish, especially in the improv scene, and really able to connect with a lot of different people, especially with those associated with Cafe Racer and greater than that, [the label] Table & Chairs. So I’ve been able to be part of some really cool things like play in the Seattle Improvised Music Festival and host a few sessions as well. The improv community here, to me, has always been a positive environment and has been a really nurturing space for me to develop and explore new ideas.

AF: What are some of your artistic inspirations?

EM: I will start with some music influences – I mean coming from a classical background, yes, there are a few composers that stick out. Being a cellist, Bach is a huge influence to me especially in terms of like how I think about improv, and I’m a really big fan of using double stops and I think about intervals pretty much constantly when creating my music. Having learned a good amount of the suites there’s a lot of double stop work in there and a lot of chord work. I think that has, one, made my left hand very strong because I really like to push all the limits, try to get all the weird stretched out chords as I can. Bach is definitely an influence, and I’m sure all cellists would say that, just that kind of style of thick chords and things like that. Also, when I was younger, Shostakovich was a great – his concept of melody. He was someone who lived in extremely dark times, under Stalin and horrible government, and was experiencing great pressure in his life and oppression. You can really hear that in his music, so from an emotional standpoint he always stuck out to me.

Sun Ra was a really great musical inspiration for me as well. My music may not be fully reflective of that – as a person and advocate for Black people in music. His love for our community. I’ve also sampled some of his work in some of my pieces as well. And really, a lot of what I’m putting into my music, the energy I’m putting behind it, is usually influenced – it isn’t even always necessarily events in my life, but just whatever I’m feeling in that moment. The overall feelings, my lived experience, if that makes sense.

AF: Once, when I saw you perform, you talked about the tortured relationship you’ve had with the cello. At the time, you talked about how a lot of your music has come out of a desire to untangle cello from the history of white supremacy in classical music. Could you talk a little bit more about that?

EM: So, at that time I had such a complicated relationship with my alma mater, to put it frankly. I had a complicated experience being one of the only black people in my department and knowing there was already a huge lack of representation there and just trying to find my place in the music world. I was really grappling with those feelings and trying to separate myself from the academia side of things and for myself realized what playing cello and music is about. From an early age I knew I was never going to be, you know, in the concert hall as a soloist, but I also knew I loved playing and for some reason people enjoyed hearing me play, so I think I was just trying to discover what was out there and possible for me as a musician.

Over the past few years I’ve gotten more experience, which alone has helped. I also switched to an electric cello and that did a lot for me to expand my sound. Also, [the electric cello] had the potential to be a lot louder, which was something new for me as well. That really opened some doors to explore my instrument, because I was literally playing on a new instrument. I [still do] some gigs where I play classical music or classical adjacent music or chamber music, things like that, but I don’t feel that burden anymore, that complicated relationship. I think I’ve been able to find what I enjoy most and really run with it. So when I do go back it’s like visiting an old friend – not to sound too corny. I am able to approach that style of music on my own terms now.

AF: Can you talk about being one of the only POC at Cornish College of the Arts?

EM: It’s not just the music department – I think in general a lot of POC students at Cornish struggle to find representation not only within Cornish as an institution but also in the curriculum being studied. I think there was a general dissatisfaction with the lack of diversity in the material we were given. I actually formed a People of Color Union at Cornish, a POC Union to help group us together and discuss what the discrepancies were within our departments and within Cornish as a whole. To put it simply, it was just trying to challenge either certain policies that the school had instated, or encourage diversity in curriculum and staff as well. One of our biggest achievements was being able to get a therapist of color on campus, which was a huge thing for us. A lot of universities and colleges, any sort of institution—they could always use a little… input.

AF: You’ve talked about using music to transform and heal. How do you think music can be used as a tool to fight what’s going on in the world right now in terms of racism and unrest?

EM: I feel like this can go so many ways. There’s the literal application of putting your personal political beliefs within music. Either through words, or making it a concept, really stamping on, like, ‘this is my statement.’ Literally using the music to fight back or to encourage change. But I think there are other avenues as well, and part of that is representation. Even if the people on stage may not be giving a political performance, it’s also very encouraging to see people that look like you or who are in your community expressing themselves as well. Someone like me, I make strictly instrumental music for the most part but I still get told that the energy I have behind my music, the values I have as a person are very prevalent. I feel just as much whether you have a verbal effect, you also have an emotional effect as well.

Even if it’s for the purpose of just bringing people together. For example, I hosted a fundraiser a couple years ago when all of the protests were happening at the detention centers. I hosted a fundraiser for Northwest Immigrants Rights Project for when the movement of families belong together was happening. But yeah, I hosted, I performed along with two of my friends and it was great. We definitely had some good messages in between. We had a wonderful host that reminded everyone why they were there. But at the end of the day we didn’t necessarily have anything to do with immigrant rights or detention centers but it was just having music there in that space, that energy present really made an impact for folks.

AF: When did you start considering yourself an activist and getting more involved?

EM: I mainly started getting involved in things when I was around 19 or 20 – really the Black Lives Matter movement as a whole got me more politically involved in things. I remember I hosted a silent protest once, just me and one other person. That was the first time I did a political action, if you will. And I also participated in a lot of the protests that were happening in 2015. That must have been the officer who killed Mike Brown – that was a big, especially here in Seattle. There was a really big explosive impact and was kind of the start of BLM activity in Seattle. That was when the original chapter was started. So I started getting more involved that way and participated in some protests. There I mainly focused on ways I could act within Cornish since that was the context of most of my life – that’s when I created the POC Union and we put together a yearly show for people of color there and that was really great, and I was in a lot of meetings with administration really trying to push for change there. At my last year at Cornish in 2017, I was an organizer for the Women’s March on Seattle, the first one. For me personally it was a big mess, but it made me learn a lot about grassroots organizing, what I like and didn’t like about it, and got me back into getting more involved in the political scene, since I was finishing school at the time.

At the end of 2017, myself and two other individuals founded Black Lives Matter Seattle – King County as the original chapter had been long gone and dissolved by then. Myself and two others founded that at the end of 2017, and we created our board, got incorporated and got all the official business out of the way. We do go by BLM-Seattle too, for short, but in our mission we incorporate all of King County.

AF: I saw you posted on Facebook about protests – I’ve heard that the BLM activists weren’t involved in a lot of the Seattle protests over the weekend, is that true?

EM: It’s about half and half. It’s been hard to decipher information, but essentially there was one protest – well, let’s back up. There was a protest happening on Friday that was organized by local anarchist and leftist groups. There was a demonstration on Saturday at noon that was being put on by a white ally [who] brought in some people from the King County NAACP [to speak]. And then there was another one that happened later that day that was hosted by a black organization called Not This Time, and they’re most known for putting on the campaign to get I-940 passed, that’s what they’re connected with. And then there’s another demonstration happening on June 14th, that claims to be the original BLM “chapter,” but it is an individual who was involved in those movements back then. He essentially hosts the majority of any protest that we’ve seen with Black Lives Matter. You know how they have the Black Lives Matter Friday and things like that? He is hosted those events. He’s an individual, not a chapter. There’s a lot of confusion.

AF: It is really confusing. It all gets muddled on social media too. Can you tell me how the George Floyd protests have affected you, and have you been involved in any of them through BLM or individually? Can you clarify your BLM chapter’s stance on protesting during the pandemic?

EM: It was a pretty tough decision – a lot of events were popping up this past weekend, and as we’ve seen continuing throughout the week, so as an organization our board is not currently hosting any in-person protests for a couple reasons, the main reason being we’re still in the pandemic, COVID-19 is still extremely vicious and prominent within black and brown communities, and as an organization we figured it would not be best to encourage our community to go out and protest. We are a thousand percent behind those who do feel the need to demonstrate and we’re not going to tell people not to protest because we fully understand why people do, but if they’re feeling on the fence about it, we want people to know we are understanding of the fact that we are still in a pandemic. We do care about our community first. In lieu of that, we have mainly been working behind the scenes to provide support for those who are deciding to protest. So, we have created our bail fund which got fully funded, and which I am extremely excited about. We created a protester safety guide that is on our website. It has COVID safety information as well as a lot of different resources for folks that are going to be out there. And then, with the bail fund we are also working on helping bail out protesters who are getting arrested. That’s all happening right now.

It’s such a weird juxtaposition of feelings — there’s so much crisis happening, I’m emotionally exhausted and there’s so much grief happening, but at the same time it has been extremely encouraging to see how much community support we’ve been getting. Our [local] chapter has not gotten this type of attention ever really and we’ve been around almost two years and have been doing a lot of really great work. It’s been really incredible seeing people come out to support us and support the work we do [and] we’re still with our community and still want to support people in any way we can.

AF: What can the music community do to support BLM and more broadly, POC musicians?

EM: I have a lot of different thoughts pop up. I think a really great example is the Seattle Symphony hosting a march, which I was really shocked at! I thought it was really cool. It goes back to my personal experience – there’s still a lot of racism and sexism within music community, especially in the classical music community, and there’s always so many talks about how we create diversity within classical music, whether it be on stage or in the concert hall. How do we do outreach, how do we make this music accessible to people? Performances are going to be on hold for a long time so this is the perfect time to really strategize on how we can make classical music in particular more accessible to marginalized communities, whether it be in education, or performance, or just accessibility to hearing that kind of music. A lot of symphonies and organizations and music unions and educators should be thinking about those things. It’s really reflective of the amount of time that I’ve been criticized because I couldn’t afford lessons, because my mom was working two jobs so I could go to my arts high school. Lack of resources [is something] a lot of young Black and POC kids experience when trying to pursue a field that’s incredibly expensive. I think this is the perfect time to think about that.

In terms of the greater music scene, especially when we’re all starting to really feel the effects of COVID-19 in terms of our work, supporting Black and POC musicians, making sure their music is getting played and they’re getting the support they deserve. Again, it just comes back to that – even in mainstream festivals, there’s still a big lack of diversity. So again, how do you make sure you’re curating your venues to really be diverse – not to just tokenize, but truly be diverse. What audiences are you really advertising towards? Who’s your audience and why? What crowds do you want in your establishment? There’s still gatekeeping in that sense. I can very much tell if the space has me in mind or not, whether I’m playing at a venue or attending one.

AF: Speaking of taking advantage of the pause, what do you think about #theshowmustbepaused social media campaign?

EM: It turned into a giant mess. I didn’t even actually know that it was started by the music community. I think people very quickly realized how damaging it could be to fill up a very relevant hashtag with a bunch of blank images. I think people understood the harm that has caused, but to the original purpose of it, what it was meant to be, it wasn’t anyone’s fault that it got misconstrued. That’s just how social media works at times. From what I remember from reading, it was a way for the music community not to promote anything and really pause everything to honor POC.

My personal feelings on actions like that, while I think the visual and yes the more performative aspect of those types of actions can have a lot of impact on people, for someone like myself who’s been doing this work and been involved in this type of environment for a long time, concrete action and consistent concrete action is always the most impactful. I always tell people, any action you do, you can do one really big action but it may not be as worthwhile as even like a smaller but very consistent action. As we always say it’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon. In two weeks, Black people are still unfortunately at high risk of getting killed by police in this country. These record companies want to take a stand – that’s great, but again, you really need to apply that in all elements of your company. Who you’re signing, payment of your artists, the money they’re able to make from you and feel supported and feel represented as well.

Stay tuned to Ebony Miranda’s website for ongoing updates and new music.