Perusing through Julia Wolf’s Instagram, the combination of quirky photoshopped selfies, documentary style videos shot with her younger sister, and peeks into her songwriting process made her feel instantly familiar to me – like someone I may have grown up with, or met at the classical music festivals I attended as a kid. As it turns out, we haven’t crossed paths in this lifetime, but in conversation her vulnerability and openness was magnetic. A classically trained pianist, vocalist, and brilliant top liner – WOLF’s music embodies old soul dynamic energy with a modern flare and 808s. The stage name WOLF was actually inspired by her little sister’s childhood protective imaginary friend. “Every night she’d say, ‘Good night, Wolf’ to her imaginary pet. It kind of just stuck with us through the years,” she remembers. “She still says it now, just out of habit.” It was a natural choice for Julia’s stage name, which she says she “didn’t want to be super contemporary – I wanted something that was going to really stand out.”

Wolf began releasing songs last year, beginning with “Captions,” “Immortale,” and “Chlorine,” introducing her honey silk vocal tone and confessional, stream-of-consciousness lyrical style: “The nostalgia trips me up/I miss being small like the first time/Driving with no parents in the car/Need to stop quitting before I start/Got my flip flops cutting me up while I walk.” The cadence of her flow and succinct melodies expressed a duality of emotional depth and vulnerability with a pinch of defiance and empowerment. A love child from a cross-genre mixtape your first crush made for you in middle school, wrapped in aged holiday paper, slipped through the space between the window and the seat on the after school bus.

Since the age of seven, Julia Wolf found refuge playing classical music on a white baby grand piano that was gifted as surprise from her father to nurture and develop her musical talents. A rigid dichotomy between social introversion and a passion for performance eventually led to routine participation at her school’s talent shows. “As a teenager I was extremely shy, and I just couldn’t talk to people. It didn’t make any sense why I was always performing, but it was the one thing that I just loved to do,” she says. “Eventually my teacher said, if you want to perform in the senior showcase talent show, it has to be an original song. I was mortified. My first song kind of wrote itself. It was about my best friend at the time. I was a senior, and she was a junior. I was going to be leaving for college and it was about always finding time for each other no matter what. Although I couldn’t connect with most people face to face, it was surprisingly easy for me to express myself through songwriting, almost an unhealthy justification for being so quiet.” Though that song is unreleased, Wolf dissects these indelible personality traits on recent single “Pillow”: “I will never act like something I’m not/Don’t blame my shyness/I just don’t wanna talk/But I think a lot/People can interpret it however they want.”

Though her songs seem effortless and natural, it took a long time for Wolf to bring them to life. She studied at the SUNY Purchase Conservatory of Music, focusing on music composition and taking a gap year to study classical under Darren Solomon, who encouraged Julia to consider a future as a concert pianist. She eventually returned to her left-field indie pop songs, independently producing demos out of necessity, but they fell just short of what she longed to achieve with them. “Throughout college and then the years following that, I was constantly hitting up different producers because my knowledge only took me to a certain level,” she says. “It still wasn’t matching what was in my head. Trying to find people to work with was so unsuccessful. It became really heartbreaking because I would send demos to be mixed and I would get mixes back that were literally unrecognizable. I even cried, and I’m not a crier.”

This disappointment led to her father suggesting a return to his hometown in Italy and starting a family run pizza business. Both of Wolf’s parents are native Italians – you can hear Wolf’s heritage in bilingual single “Immortale” – and felt that a fresh start as an American artist in Italy would provide a new beginning for Julia and be a good move for the family overall. At first, Wolf didn’t see it that way. “I just was so devastated. I thought my music career wasn’t going to work out for me based solely on the fact that I just couldn’t find people to help bring to life the vision,” she says.

A serendipitous internet connection with Jackson Foote (of NYC-based electro-pop duo Loote) changed everything. Foote stumbled upon a soundbite from a live performance posted on WOLF’s Instagram story and casually asked if he could take a stab at flushing out production for the track. “I had been searching for collaborative artists for years before meeting Jackson and it was one dead end after the next. I never realized finding someone on the same wavelength as me, who understood the sound I wanted, would be so completely impossible,” Wolf says. “But when Jackson and I started working together there were two things I immediately knew: one was how rare our musical alignment was, and two that I wanted to continue working with him for as long as our creativity would let us.” This organic partnership would eventually birth the first batch of tracks that matched her true sonic vision. Her cross-genre, R&B-tinged pop has since gone viral on Spotify.

Wolf’s distinctive music style might come as a surprise to some; she says she’s often pigeonholed as the singer-songwriter type at a glance. “When people look at me… they’re always surprised when I say, like, yeah, I listen to rap or, you know, this is what my music sounds like,” she says. “I feel like I have definitely been boxed in, at least for like the beginning half of my career. And that’s why I never put music out, because it wasn’t exactly what I was envisioning to represent myself.”

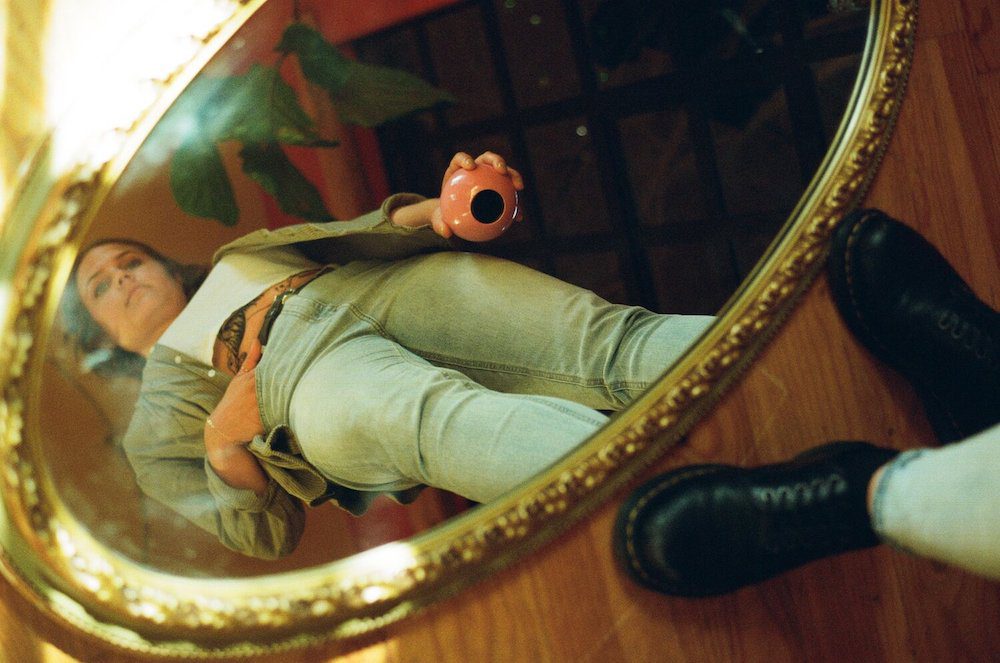

By teaching herself Photoshop, Wolf’s surrealist artwork (heavily inspired by the album art of Tyler the Creator) completes her sonic world. Her imagery carves out a unique visual space for the project, and separates Wolf from the typical self-promoting artists taking selfies at coffee shops in Silver Lake. She creates whimsical collages, layering skeleton fingers over a fleshed out hand holding a vintage mirror, shooting laser beams or dribbling crystalized tear drops from her deep set eyes.

The lyrics always come first for Wolf as the main focal point followed by the melody. She gets most of her inspiration from Soundcloud, where she spends time discovering up-and-coming rappers. She’s also heavily influenced by the lyricism and genius of Frank Ocean: “It’s just really the attention to detail that I love so much about him and the way he could say so much with so little. I think that’s one of the hardest things to do, is to just simplify how you’re feeling,” she says. She says SZA is another big influence for the same reason, adding, “I’ve always gravitated towards rap. I don’t know if it’s the beat that’s behind it or the change up in flow and being able to keep a song so interesting without melody. Blows my mind.” You can hear those influences strongly on her latest single, “Play Dead,” which dissects the “evil” behavior she’s guilty of acting out in a doomed relationship. But she’s also inspired by pop punk bands like The Front Bottoms. “I was always the first in the mosh pit, and really let loose,” she says. “Their live shows are just so much fun, and it’s also inspiring to see people storm the stage and just feel like they can completely be themselves.”

Wolf has been riding out the pandemic in NYC, and while the isolation is not unusual for a writer who values her solitude, she says, the biggest difference between her normal hermetic routine and quarantine is that the latter “feels way more forced – and that has definitely challenged the creative process.” Of course, the location itself has a silver lining. “Being in NYC in general has taught me that artists can find inspiration in all types of circumstances; there’s a fundamental need to create when you feel you have something to say,” Wolf points out. “The state of the world right now is a heavy mixture of chaos, unjustness, sadness… but watching people create change is 100% motivating and highlights the beauty that comes from speaking your truth.”

For now, her plan is to drop a few more singles before turning her gaze to a full-length release. “I’m getting a lot closer to releasing an album but want to make sure the timing is right,” she says. “It’s a body of work I’m proud of and while I’m tempted to just release it, like most things in life, rushing always backfires.”

Follow WOLF on Facebook for ongoing updates.