The live music experience is a major part of music fandom, and anyone who attends concerts regularly can attest that there’s an unspoken sense in the air of how to behave and interact with one another at most shows. In venues of any size, hosting any band, of any genre, there is simple etiquette that one makes a contract to uphold as soon as they enter the venue’s doors. Sometimes though, for whatever reason, folks in the audience just don’t get the message, ignoring body language, personal space, and common decency, which can make for an unpleasant experience for everyone around. Here, we lay out the do’s and don’ts of show-going, explicitly stating that unspoken language once and for all.

First, let’s go through some of the people you may encounter at shows. This does not go for all shows or all genres, but as a photographer and writer who covers live music often, I’ve become familiar with certain types of folks I often share space with. It’s important to identify these people so you know how to deal with them at your next show.

Here With Friends

This person is typically just along for the ride, more than likely traveling in a pack and sticking with them through the entirety of the show. These people are generally harmless – just be on the lookout if they start to hype each other up a bit too much throughout the band’s set. But even that is better than a big clump of people only there to shmooze, who talk throughout the show about things unrelated to music – especially if the set is quiet. Though they may not talk to anybody else in the crowd, random conversations can be distracting; if it seems like this is going to be the case, seek refuge away from the group.

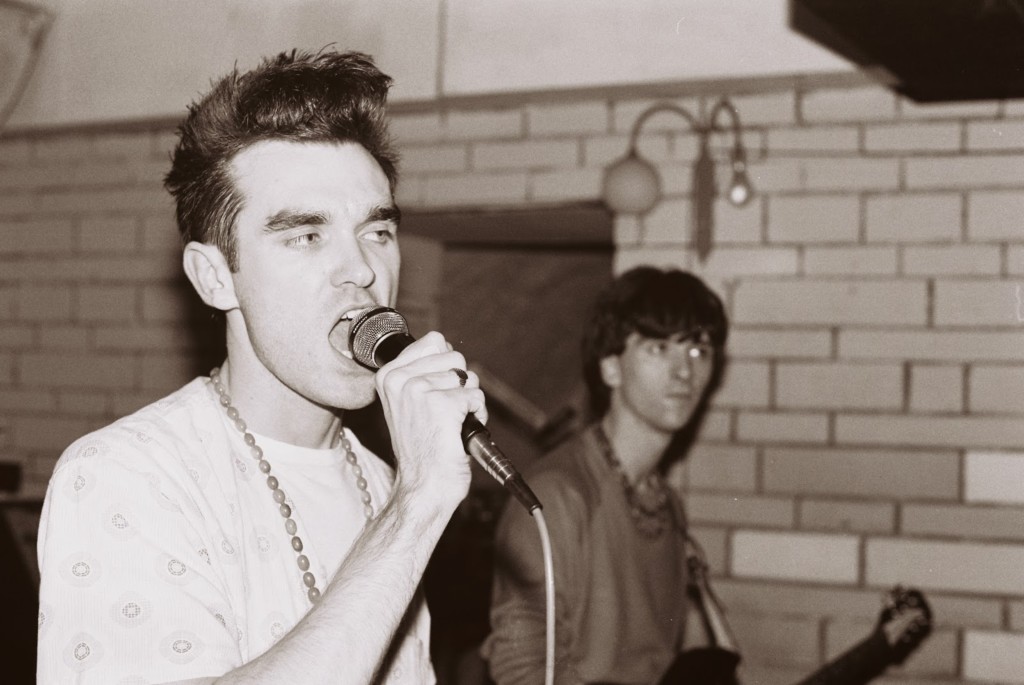

Die-Hard Fan

If the show is at a larger venue or is a really noted act, you might get those die-hard fans who will go early and wait in long lines to see their favorite band from a prime position. They will be at the front of the stage, screaming every lyric of every song, their unconditional love for whatever act they’re seeing undoubtedly noted by the freshly-purchased merchandise they’re wearing or some attempt to drop random facts about the act between songs. They may get wild, but it’s all for love of the music – generally you can count on this person to promote positive vibes in the folks around them, whether they’re alone or with a friend.

Wacky Flailing Arm Inflatable Tube Man

You will probably see this person in the middle of the venue, as they are often a part of the pit – maybe even the pit starter. Common at hardcore, punk, and even certain types of hip-hop shows, they flail their arms and legs all over the place to build a circle around them and are not to be reckoned or reasoned with. If they’re getting a pit started that you don’t want to be involved in, try and stay safe while giving them space to do their thing. It’s a little more awkward when someone’s just flailing for no apparent reason, but oftentimes these are the people who will be most offended when confronted, so subtle glaring or switching up your spot is all you can really do.

IPA Dude

Outside of shows, you’ll see this person at bars, at coffee shops, at Whole Foods, or walking across the street with their fixed-gear bike. They hold on to their beer like it’s their lifeline and probably won’t stray far from the bar of the venue so they’re able to order again quickly. If they’re not already friends with the bartender, they will be by night’s end, and will hopefully remain chill even if they have one or two too many. They might be very vocal with their opinions on beer, coffee, or even the music, but they can be cool to hang around with if you just want to enjoy your time by the bar, removed from the crowd.

Arms on Lockdown

Similar to IPA Dude, this person is very chill. Usually coming by themselves, they keep their arms and legs to themselves and inside of the ride at all times. They’re just there to enjoy the music, and not be bothered. Just like a bee, if you leave them alone, they’ll be harmless, but it’s likely they take things very seriously – seriously enough that if they’re standing next to Wacky Flailing Arm Inflatable Tube Man or a group of loud talkers there might be a showdown.

Surf’s Up!

We all know those who crowd surf. It is a sport and a gift to those who are comfortable enough to be lifted up by complete strangers and passed along sweaty palms to prove their love and joy of the band. Sometimes they barrel to the front to jump off the stage and into the crowd; other times, they’ll get bystanders to hoist them up and surf toward the stage. They may not appear so before the opening song, but those first few riffs transform them into a thrill-seeker. Once they’re up, it’s hard for them to control where they go or what they’re doing with their own limbs, so if you’re anywhere in their path, stay alert! Doc Martens to the forehead do not feel good.

The Photographer

As a photographer myself, I’ll say this: even though some of us are working, we are just fanatical as anyone else. We typically love the bands we shoot, we love the thrill of a live act, and we love to document that. We have to be near the stage to get good shots, and with that comes some risks. We dodge crowd surfers, flailing arm people, pit-pushers, and more, often with expensive equipment that we’d prefer not to break. A good photographer shouldn’t distract you from the main act – most will get in and get out once they’ve got what they need. If you’re near an amateur with an iPhone who sees a need to record video of every song in its entirety, that’s another story – politely remind them that they’re blocking your view when they do that and ask them to keep documenting the event to a minimum, and hope that they’ll oblige.

Push Pops

At some shows, there may the tamer cousin to the mosh pit – the push pit. The push pit mostly contains people jumping up and down and having a good time. It is a uniform mass and is easy to get in and out of. Those who decide to be a part of this mass are usually not aggressive, but have a gigantic love and appreciation for the band, and let that excitement show with high-energy movements. Joining in can be really fun, and it’s great cardio too!

Needless to say, a crowd encompasses many types of people, and works almost like its own organism, reacting to the same stimuli. No matter what type describes your own show-going persona, there is some behavioral protocol that should be followed when attending a show. We all want to enjoy the experience, get our money’s worth, and leave happy. But one or two unpleasant folks can sour the mood for everyone, instead bringing negativity and sometimes even danger to the audience around them. Here are some best practices to be conscious of when you’re at a show.

Most importantly: R-E-S-P-E-C-T isn’t just a song by Aretha Franklin (RIP), it’s something that everyone in general life should exhibit, both spoken and silent. In the close quarters of a sold-out venue, this goes double, and the easiest way to tell if a given behavior is acceptable is to look around you. Observe the crowd – if no one’s dancing or moving around at all, it’s probably not an appropriate time to start up a pit and start pushing people around. Though it seems like common sense, unfortunately, some people are lacking of that.

Respect also comes in the form of respecting physical boundaries. Although sometimes show-goers are packed like sardines into a venue, it does not mean that someone should be touched without permission and personal space should always be 100% respected, as best you can. Even a tap on the shoulder can make someone feel uncomfortable, and shoving people aside to get a spot in front of the band is pretty rude. If someone’s in the pit it’s probably safe to say they’re open to the types of touching that come along with that, but – especially for people in the pit periphery who aren’t active participants, keep your hands to yourself.

The pit can be an amazing experience to be a part of, but it’s also a complicated one. Unfortunately, the pit is heavily dependent on social cues, therefore communication can be misinterpreted. For the most part, even folks who appear aggressive want everyone to have a good time too, and there’s a good deal of helping people up when they fall or doing some protective pushing around smaller moshers.

If you do not want to participate in jumping around, possible pushing, fist-pumping or any of that action, it is recommended that you find a small space where you will not be affected by said pit. Standing along the wall or in corners is a great option as these provide pockets of space where the pit will more than likely not open up, yet you’re able to see the action both on stage and off. If someone keeps pushing you or trying to throw you into the pit from the sides, feel free to tell them to back off, but don’t act hostile about it since you don’t want to start beef with someone who can put you in harm’s way. If you’re not dying to see the act up and close, going to the back of the venue can put you in the arms of safety. It allows you to be close to the exits and possibly the bar, so you don’t have to interact with the pit people at all.

If you’re going into the pit, don’t do anything more aggressive than you’d want done to you. If you don’t want to get punched, don’t punch people. It’s as simple as that. It’s sad that this has to be said, but countless times, people have been more aggressive than they need to be. If you’re in a pit and other people are knocking into each other and pushing around, cool. But if people are starting to grab one another by their shirts, push people down to the ground or grab anyone to the point where that person is out of control, don’t hesitate to notify someone. A lot of shows at bigger venues have competent security. Some bands have even been known to call out bad behavior they see in the audience. But whether it’s happening to you or someone nearby, don’t just do nothing. The more aware that people are about a potentially violent or offensive person, the safer that environment can be.

Be observant of the venue around you, too. Be aware that the space needed for a pit can push other people into uncomfortable nooks and crannies. Assess your space before you decide to flail your arms everywhere or bring the pit further into the back or sides of the venue. Sometimes it’s appropriate and other times it’s not.

The pit can be a unique and fun experience if people can observe behavior and assess before they act. It takes at most five seconds to turn around and look at the people to your left and right and anticipate their next move. You’d do the same if you’re about to turn a corner on a street, so bring those same principles to a show.

Be a Conscious Observer.

Safety should always be your main concern, even if that doesn’t seem “cool.” Observe and assess your surroundings; with violent events at concerts on the rise, it’s important to know where to go in case of emergency. Also, don’t be afraid to say hello to whoever is nearby you, and make sure they are aware of your presence. Whether offering a simple wave or friendly eye contact, noting your neighbors may help you in the long run if something were to happen, and even if nothing does, you might make a new friend.

It’s also important to note other people’s behaviors. Pit or no pit, some people may act in an unruly or uncomfortable way that can not only effect yourself, but other people in the crowd. Don’t be afraid to speak up if someone is making you or another person uncomfortable. Talk to the bartender, security, someone next to you, the box office attendant, even the band. Try to prevent a person from doing something potentially threatening and dangerous without direct conflict.

Don’t Be An Asshole.

Pit ettiquette boils down to that one simple phrase. If you wouldn’t want it done to yourself, don’t do it. It’s very easy to be nice, but’s also easy to cross that line when you’re in the midst of your favorite song.

Courtesy extends to the bands providing the music; unless they have asked for requests, don’t heckle them with suggestions for their set list. Bands put time and thought into crafting their set list and try to get a good range of music played to make their audience happy. Sorry if that one obscure song from their very first album wasn’t played – ask yourself if you really wanted to hear it, or if you’re just posturing for those around you so that they know what a longtime fan you’ve been (FYI: no one cares, and true fans come to hear what the band is interested in playing). At the end of the day, though the band is hopefully grateful to have an audience to play for, it’s also an opportunity to play what they’re excited to play, and recycling the same old tunes can get boring on a long tour. Just because you paid money to see them perform does not give you the right to dictate how and what they should play.

Here’s an important one, if you are tall. Please. Let. Short. People. FORWARD. If you’re plagued with the short gene like I am (I’m 5’1”) then it can become difficult to see the band through a sliver of space between two people who are much taller than you, and no one wants to stare at someone’s shoulders and neck all night.

Bottom line: show-goers want to get the most out of the shows that they go to, and the bands that play want to see their audience have fun. If “fun” entails pushing people around in a mosh pit all night for some, and standing by the bar with arms crossed for others, remember: there’s room for all types of fandom, but all are governed by a golden rule. It’s easy to be nice, so why not do it? You’re there for the music, sure – but also for the experience of being in the midst of a living, breathing crowd, so taking it all in and putting out positivity in turn is the best way to make sure everyone has a blast.