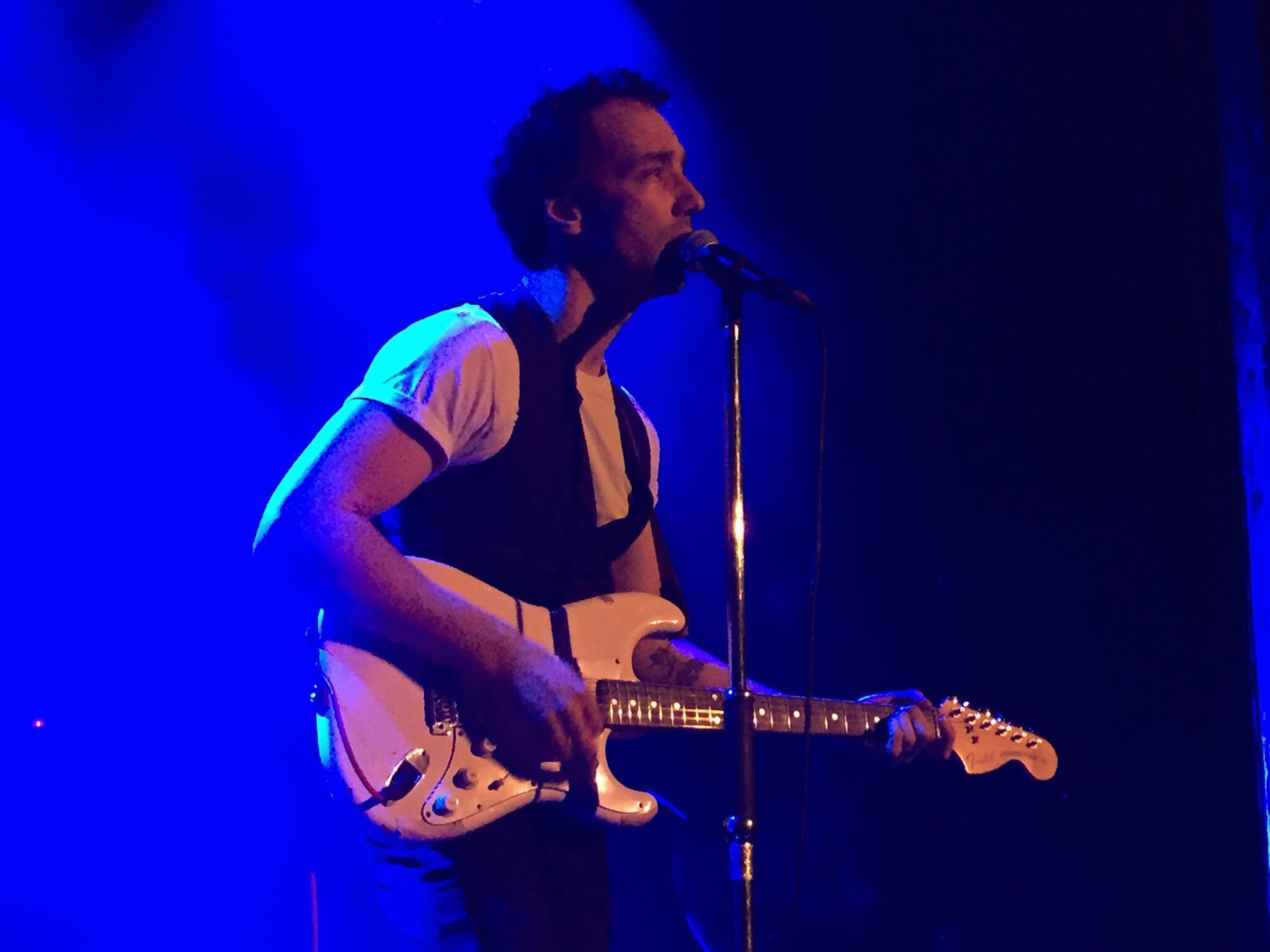

“Guitar is the great lighthouse of my life,” says Daniel Donato. The musician speaks with gusto about his work ─ and for good reason. On his debut album, A Young Man’s Country, he invites the listener into what it must be like for his live shows, and he dazzles not only with his thoughtful songwriting but his guitar work. Many of the songs, including “Always Been a Lover” and “Broke Down,” hinge on his ability to tell compelling stories with only his guitar. Strings crash along the melody lines with shocking electricity, and his choices are so rash and unexpected, you never know where he’ll lead next. Guitar solos range from seconds to several minutes, highlighting the album’s entrancing ambiance.

“With this record, I have a love letter proving that I am finding my own style,” he tells Audiofemme. Donato has gone on record citing such guitar legends as Brent Mason, Chet Atkins, and Jimi Hendrix as direct playing touchpoints, but across eleven songs, it appears he has finally unlocked his very own high-energy aesthetic. “I don’t think style is something arrived at, something found,” he says. “It is in a constant ebb and flow of change. That is, if you’re working on it diligently with truthful intention.”

A Nashville native, Donato’s musical interests were sparked early on by Guitar Hero, but he quickly left the video game behind and spent his teenage years leaving his imprint all over town. He gigged a number of years as lead guitarist for the Don Kelly Band, busked along lower Broadway, played every honky-tonk he could (including Robert’s Western World), and even wrote a revolutionary book called The New Master of the Telecaster when he was 18. Now 25, the accomplished musician has more than proven himself.

In a 2015 interview with TC Electronic, he expressed deep desires to tour and be his own artist, eyeing a slew of records. Well, life had other things in store, and time got away from him. But he doesn’t mind that it’s taken five years for a proper debut. “Time is a fascinating plastic energy that changes and morphs all of the time, especially during these times,” he muses, “but I’ve been dedicating my life to music for eleven years, every day, so five years is just the start of it for me.”

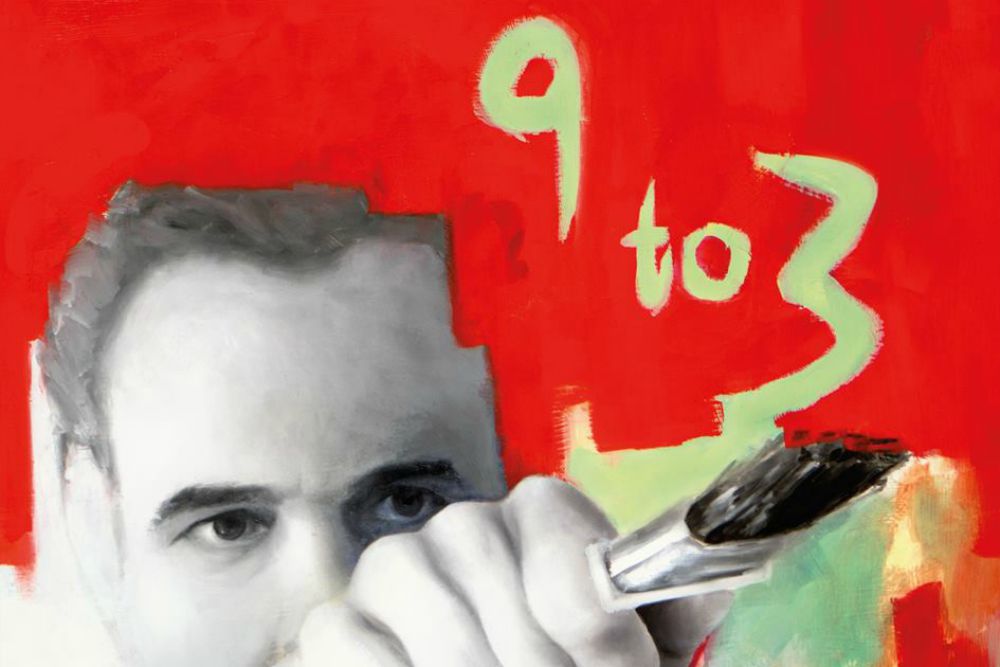

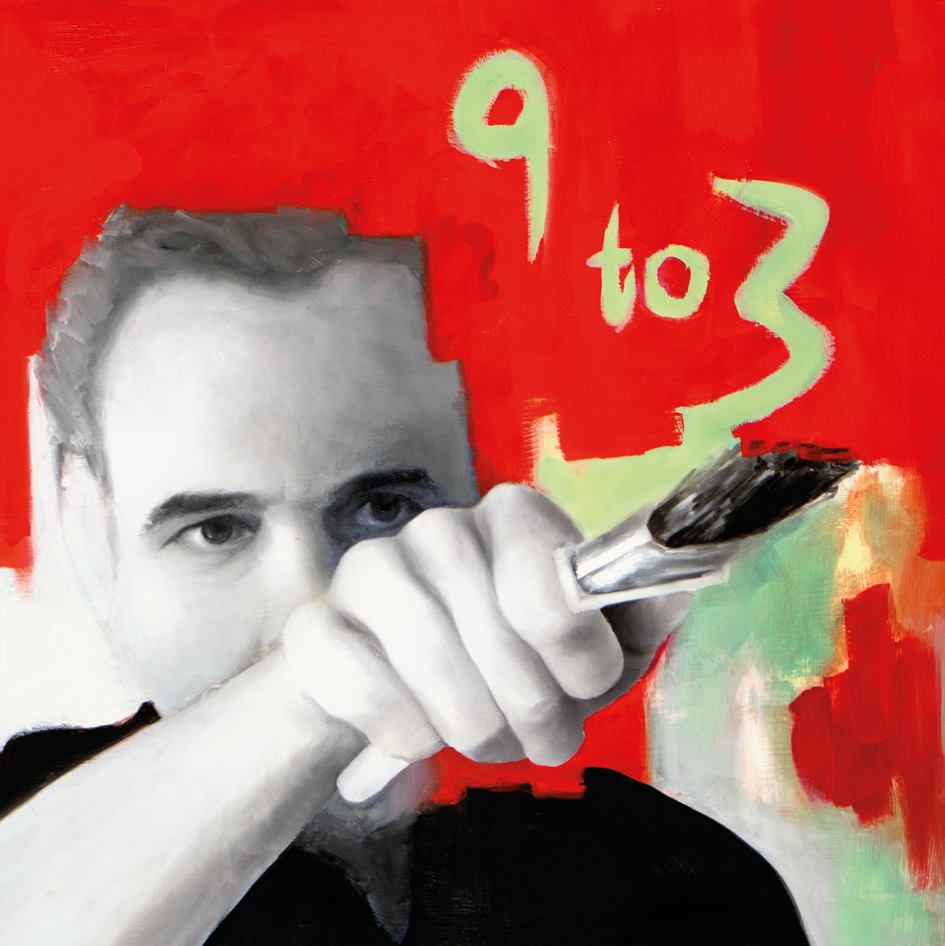

Donato dropped two EPs in 2019: Modern Machine and Starlight, two pieces to a much larger puzzle. Most of those songs fit onto the new record, but in a different sequence, the listener is called into an exuberant, lively, and free-spirited world fashioned with curiosity and freedom. It exists to showcase his gifts, of course, but also functions as existential exhibit.

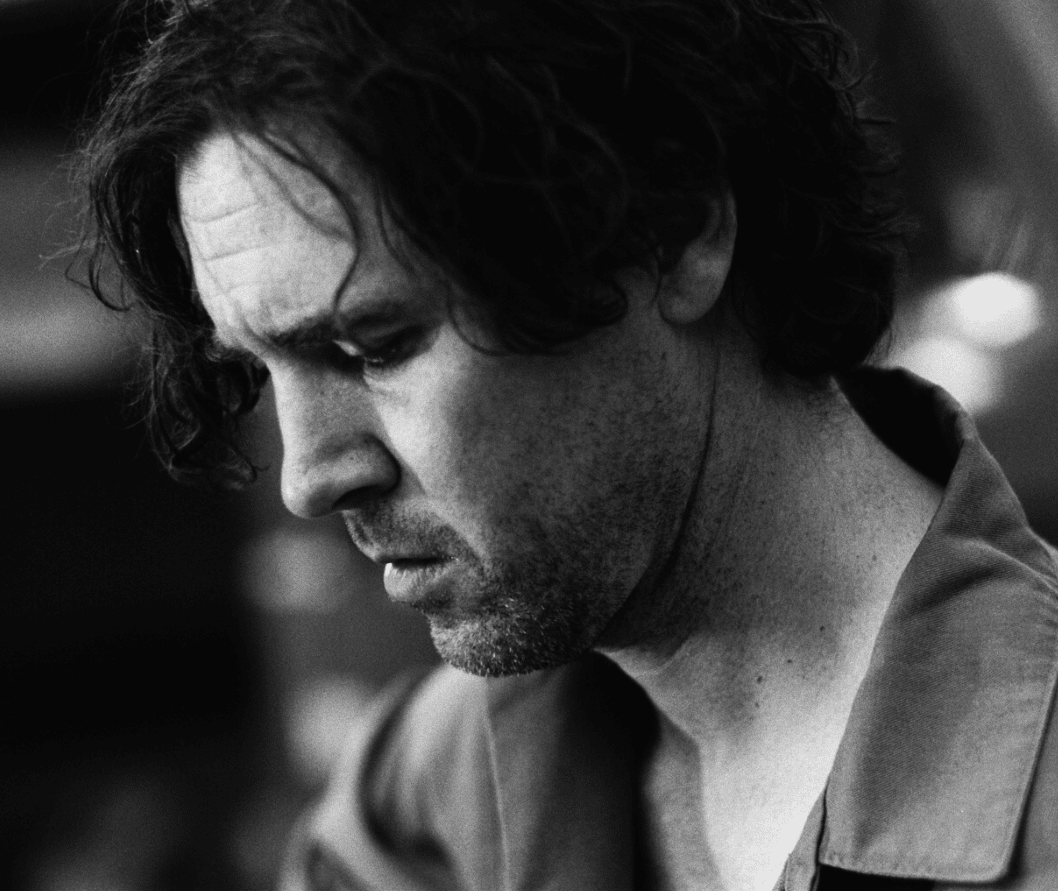

“[This album is] about accepting the fact that you won’t be young forever. Mortality is the first fact of any matter,” he explains. “So, while I am young, I am going to play that way. I’ll have decades of being able to tone it down and apply less is more. So many people in Nashville are about this, but what has always inspired me are the people who play like their life depends on it. That’s what Jerry Garcia did every night. The first waving of the Cosmic Country flag into the world had to be as pungent and unique as possible. It is the way I am, as Merle Haggard had said, simply.”

A Young Man’s Country still bears marks of an artist still finding his groove. “I work out loud. I am not a perfectionist. I work, put it out, and listen to the people, and other life signs, on where to go next,” Donato says. “That honesty is what we owe listeners today. The masterpiece desire is not my bullseye, right now. I just want to bring value to people by figuring out my potential in real time, out loud, as often as possible.”

That philosophy comes full circle on “Diamond in the Rough,” a co-write with Paul Cauthen that takes a pair of jumper cables to the eardrums. “If I must confess, I’ve been running on no rest/Crazy just a touch, as of late, I have a hunch/That I’m blind/So I shine in the darkest night, my love/A diamond in the rough” he sings, before launching into one of the set’s most electric guitar solos. “The Cosmic Country style jam on the outro came from hours on the stage playing it live,” he says. “[Paul and I] did over 150 shows in one year; that song came from a slew of tunes written from that time in my career.”

Album closer “Ain’t Living Long Like This,” a Waylon Jennings cover, tips its hat to the original but picks up the speed with a horizon-bound gallop. Drums throb in the background and the bass line acts as a jackhammer to keep it barreling along. Many of Donato’s guitar solos ring similarly, always stimulating and ferocious, but each one stands on its own even as the record pools into a cohesive whole. He writes “from song to song,” he says, so it’s only natural the record would feel threaded together. “If I finish one, I let that song tell me where to start for the next one. That verticality is crucial to me. I want every song to feel like a Cosmic Country song. Just like how a J.R. Tolkien novel, or a Bukowski poem, clearly reads and feels like it came from that writer’s own gravitational pull.”

“I don’t know if I’m looking for a lot of contrast within this record from song to song, as much as I notice that this record as a whole sits in contrast to other records in the marketplace. If you listen to Tyler Childers, Grateful Dead, John Prine — their records sound like them for every second. Buck Owens — so many of his songs were similar that he’d play five hits by simply going from chorus to chorus, all in the same key,” Donato points out. “It’s a country music-ism, the similarity in the exoskeleton of a song.”

A Young Man’s Country (produced by Robben Ford) is composed of mostly whipping, heavily-rhythmic moments. But “Meet Me in Dallas” is one of only a few more somber performances, alongside a version of John Prine’s “Angel in Montgomery” and “Sweet Tasting Tennessee.” “I know how to be alone sometimes,” he sings on “Dallas.” Another Paul Cauthen co-write, the song literally hit him after driving 23 and a half hours from Wisconsin to Dallas while on the road.

“The second we arrived at The Belmont in Dallas, I took my guitar to Room 41 (the name of [Paul’s] most recent full length release), and I wrote it in 10 minutes,” he says. “I was in a relationship that was coming to an end at the time. That room has magic to it. So does heartbreak. So does insomnia combined with a melody in your head.”

Daniel Donato more than plants his flag in the industry. A Young Man’s Country cements him as a force to be reckoned with; its bold, sizzling guitar work sets him on a path to be one of the greats he so admires. All he needs is a bit more time. And he has plenty of that these days. In addition to his music, he interviews other musicians, songwriters, visual artists, and business people on a podcast called Lost Highway.

In reflecting on lessons learned, Donato offers this particularly sage bit of wisdom. “I’d say this philosophy can summarize a good strategy for success in life. Repeat this mantra 1,000 days in a row: Patience. Persistence. Positivity. In that order. Life starts to make a bit more sense with these parameters.”

Follow Daniel Donato on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram for ongoing updates.