It’s the hammer of justice

It’s the bell of freedom

It’s the song about love between my brothers and my sisters

All over this land.

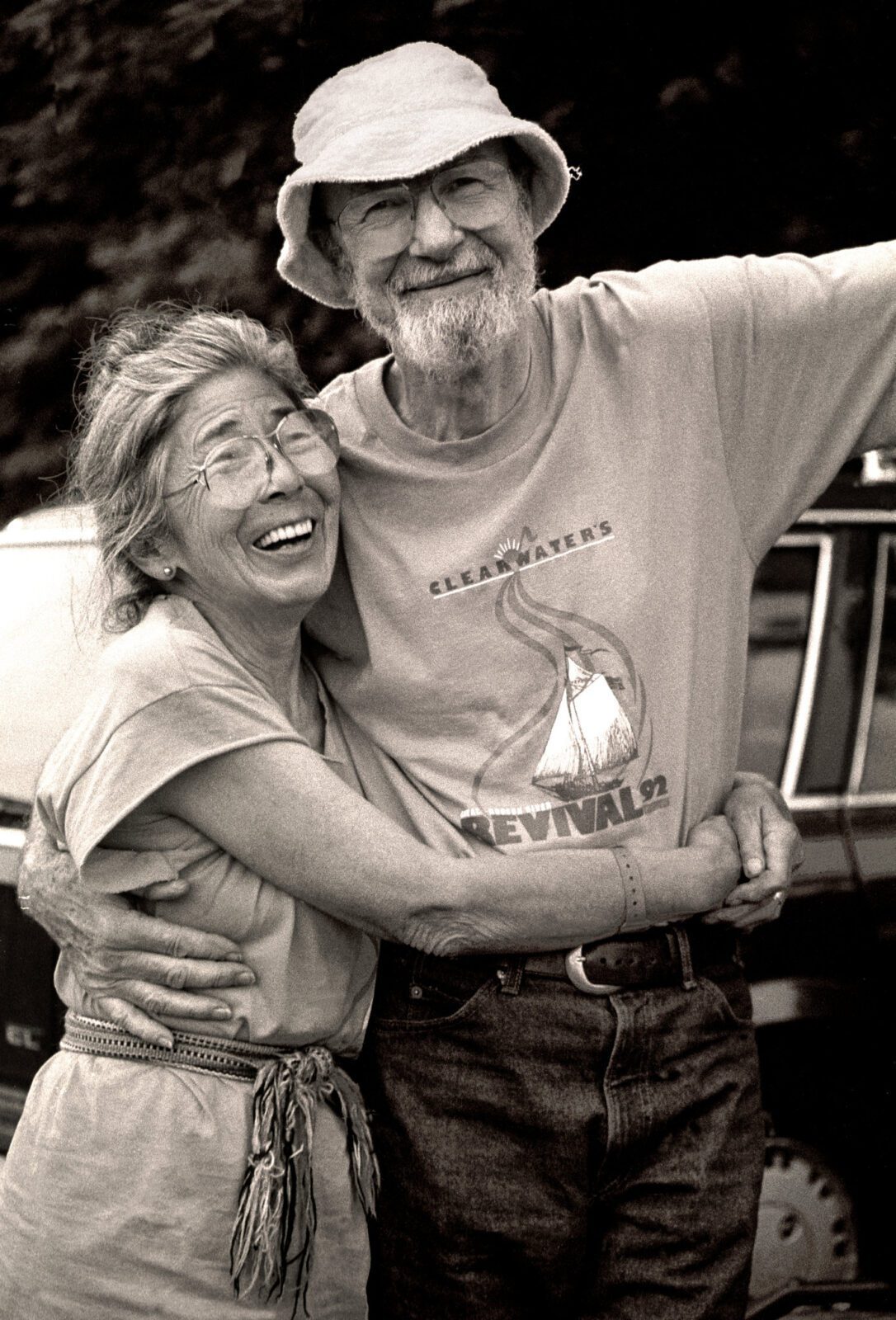

I used to go to the Hudson Clearwater festival every year as a child with my mom, dad, brother and grandparents. I’m not sure if this is a real memory or not, but one year- I must have been less than ten- I briefly met Pete Seeger. I knew nothing about him, just that he was an old man who sang folk songs that my parents and grandparents listened to when they were growing up. They told me that he was important and that I would know all about him later. Whether or not this is a real or invented memory, it is one that I’ve held onto for some reason, probably because of Pete Seeger’s influence on my own development as an ethnomusicologist and a folk music enthusiast. Pete Seeger (1919-2014) was one of the most prolific and important folk musicians of the 20th century, but his legacy extends beyond the music that he created. He was groundbreaking not only because of his music, but also because of his work as an ethnomusicologist, educator, activist and patriot. This installment of Flashback Friday remembers the music and the work of Pete Seeger.

Most American folk songs cannot be traced back to a single origin. Traditionally, music was passed down to friends and family members by word of mouth, changing slightly along the way. By the time folk songs reached their final destination, they might not even sound like the originals, yet every hand that touched them played a part in their creation. Folk music was a collective effort that took place over distance and time.

Pete Seeger understood the necessity of maintaining this songwriting tradition. As an undergraduate I studied one of Pete Seeger’s most pivotal songs, “We Shall Overcome.” “We Shall Overcome” was typically sung at protests and rallies during the civil rights era and is commonly referred to as the anthem of this movement.

“We Shall Overcome” was not only an important protest song, but it is an exemplary folk song because of its collective origins. “We Shall Overcome” evolved in the 1900s from two spirituals containing similar themes and lyrics, “I’ll Overcome Some Day” by Charles A. Tindley, and “I’ll Be Alright Some Day.” In early union meetings in South Carolina, one verse from “I’ll Be Alright Some Day” was turned into a song. In 1946, during an American Tobacco Company strike in Charleston, South Carolina, Lucille Simmons sang “We Shall Overcome.” It contained the same verse that was taken from “I’ll Be Alright Some Day,” except the “I” had changed to “we.” She also sung it in long meter style. A striker later introduced this version of the song to Zilphia Horton. She then passed it along to Pete Seeger, who implemented a steady rhythm and presented it to Guy Carawan. Guy Carawan sped up the tempo. He organized a Singing in the Movement workshop where he taught the song to seventy people. It was eventually swept up by the movement. Pete Seeger obtained songwriters credit for “We Shall Overcome,” yet he highlighted the song’s history as a spiritual and acknowledged all of the hands that played a part in its evolution.

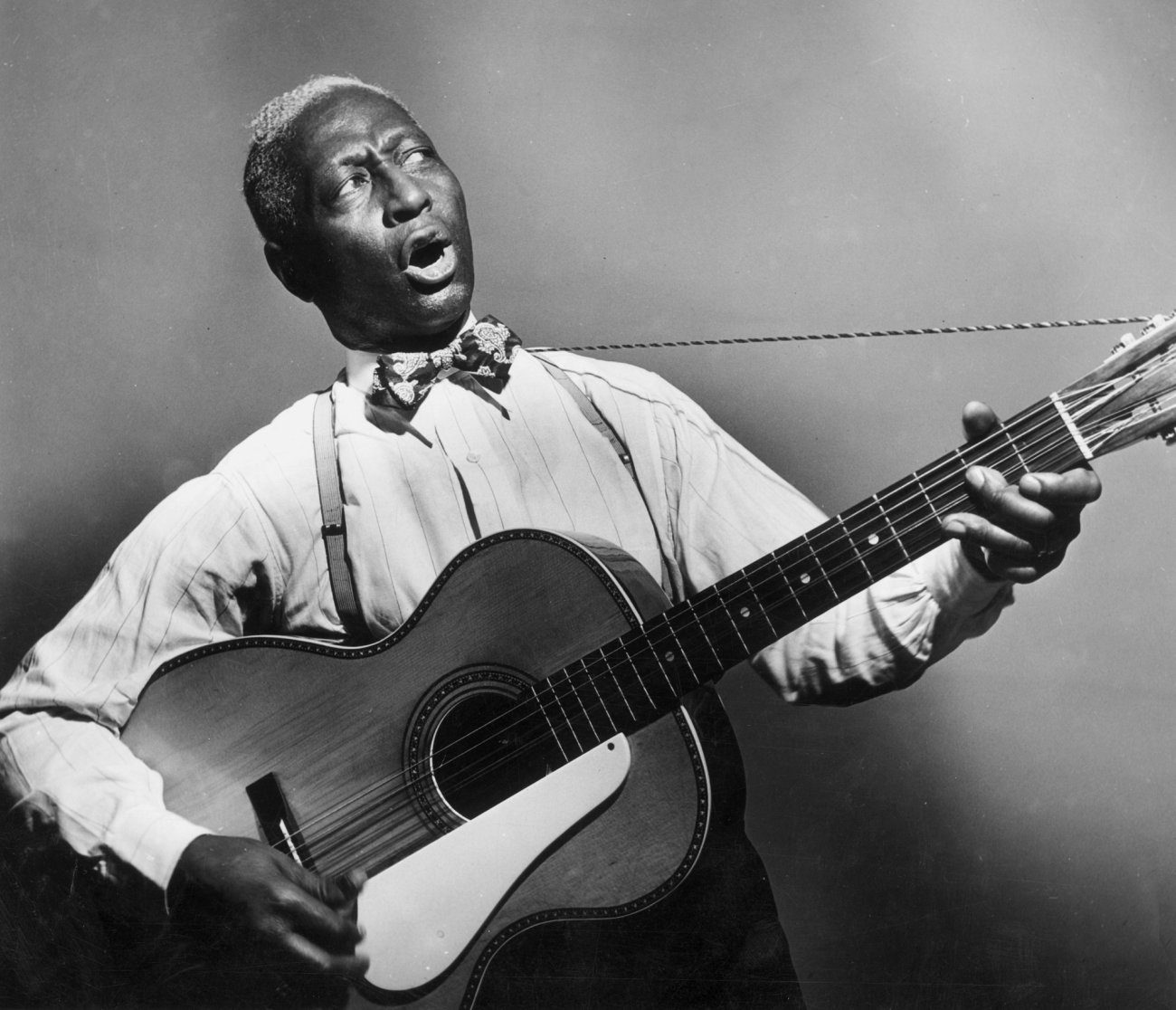

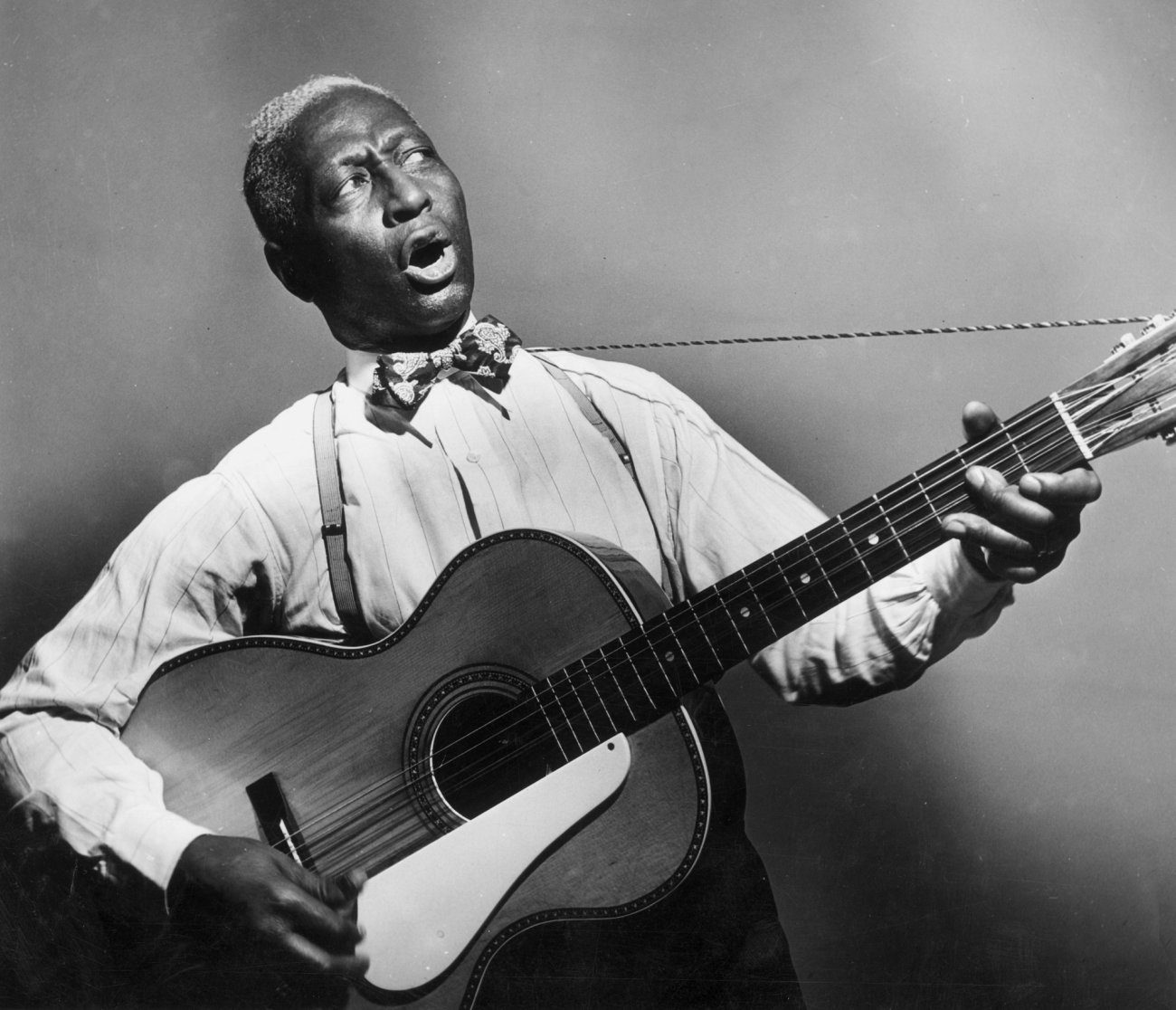

As an ethnomusicologist, it is impossible to ignore Pete Seeger’s influence on American folk music. As his father, Charles Seeger was a highly regarded ethnomusicologist, Pete Seeger developed an early interest in the discipline. In the late 1930s, Seeger worked alongside Alan Lomax, assisting him by sifting through his field recordings. He later appeared a number of times on Alan Lomax and Nicholas Ray’s broadcast show, Back Where I Come From. Folk musicians such as Josh White, Burl Ives and Lead Belly also appeared on this show alongside Seeger. Seeger also did a vast amount of fieldwork in his own right. Seeger traveled around America (and later around the world) to discover local folk traditions. Most notably, Seeger popularized the five-string banjo, an instrument that was previously constricted to the Appalachian region of America and is now known as a staple of folk and Americana music.

Pete Seeger was equally seminal as an educator of folk music. In 1954, he published How to Play the Five String Banjo, an introductory book on the banjo. Seeger went on to write a number of books, from instructional books to books on the civil rights movement and even children’s stories. Pete Seeger also led numerous talks and seminars on folk music and protested movements throughout his career. Furthermore, in 1965 Seeger hosted Rainbow Quest, an educational folk music show that featured artists such as Mississippi John Hurt, Doc Watson, Johnny Cash, June Carter, Judy Collins and Buffy Sainte-Marie.

Pete Seeger was a champion of the first amendment during a time in United States history when freedom of speech was at risk. Seeger rose to prominence amid the McCarthy era red scare. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was formed in 1938 to investigate individuals who were suspected of communist leanings. By 1950, a number of public figures were forced out of work after being blacklisted by the HUAC. Pete Seeger, a known member of the communist party since the late 1930s, had a number of run ins with the United States Government. Seeger was blacklisted in 1952 along with the rest of The Weavers.

On August 18, 1955, Seeger was brought to trial and testified before HUAC. Seeger refused to plead the fifth amendment and state his political leanings in order to protect his first amendment rights. This resulted in an indictment for the contempt of congress. He was later tried by a jury for contempt of congress and sentenced to 10 years in jail, although this charge was later overturned. Seeger was subsequently blacklisted a number of times throughout the ’50s and ’60s.

Inspired by Woody Guthrie, Seeger’s banjo was branded with the phrase “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender.” From the onset of Seeger’s career, he demonstrated music’s ability to promote social change. Although often silenced or censored by the government, Seeger continued to champion human and environmental rights locally, nationally and globally. Throughout his career Pete Seeger wrote topical songs for a number of social movements and political events (the Spanish Civil War, World War II, union’s rights, the Cuban Revolution, Chilean nueva cancion, women’s rights and civil rights, to name a few).

It’s no secret that the Hudson River used to be a lot dirtier than it is today. By the 1960s, the Hudson River was pronounced “dead,” and even unsafe for swimming or fishing. In 1966, Pete Seeger and his wife Toshi Seeger founded the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, inc.. Seeger raised funds to build the Sloop Clearwater by passing his banjo through the crowd after performances, asking folks to contribute anything that they could. In 1969, thanks to Seeger’s tireless efforts, the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater had its first inaugural sail in 1969. The Clearwater is a sailboat dedicated to conducting environmental education on the Hudson River. In celebration of its annual sail up the Hudson River, The Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, inc. produced the Great Hudson River Revival, or the Clearwater Festival at Croton Point Park. The festival, which is a celebration of folk music and environmentalism raises funds for the non-profit organization.

Richard Rorty’s famous quote “You can feel shame over your country’s behavior only to the extent to which you feel it is your country”, is especially relevant when discussing Pete Seeger. Throughout his life, Pete Seeger maintained his love for America. Pete Seeger celebrated the countryside. He knew that there were musical gems to be discovered in the foothills of the Appalachian mountains, the swamps of the Mississippi Delta and the tobacco fields of North Carolina. He dedicated much of his life to sharing those traditions with the rest of the country. Seeger maintained this patriotic fervor throughout his life, even when the government of the country that he loved was doing everything that they could to silence him.

While many folk musicians became disillusioned with protest music for various reasons, Pete Seeger maintained the importance of protest music, both long before and long after it was in vogue. Pete Seeger illustrated the timelessness of protest songs. For instance, “We Shall Overcome,” a song that was originally written for civil rights, has been re-appropriated for a number of different social movements (even as recently as Occupy Wall Street). The other day, my grandmother told me about the first time she saw Pete Seeger. She was younger than I am, and she went to a square dance in New York City, where Pete Seeger was the featured performer. While both my grandmother and I remember our first encounters with the seminal folk musician, I have no doubt that countless others have similar multi-generational stories of their own encounters. Pete Seeger’s songs will continue to be relevant long after his death, as will his accomplishments as an ethnomusicologist, an educator and an activist.

****************

“Sometimes we’ve had tears in our eyes when we joined together to sing it, but we still decided to sing it!”

-Dr. Martin Luther King Jr