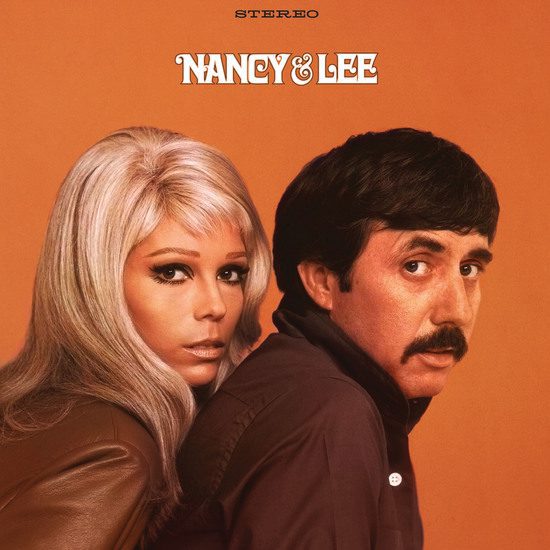

It was 1988, and Peggy Lee was finally going to take a stand. She was representing no one but herself, but she nonetheless was determined to face off against one of the largest media conglomerates in the country — Walt Disney Productions. In one corner, there was Lee, singer, songwriter, and actress. In the other, home of Mickey Mouse, numerous classic films, a cable network, and ever-expanding theme parks. David, meet Goliath.

At issue was the release of Disney’s 1955 animated feature, The Lady and the Tramp, on videocassette in 1987. Peggy Lee had co-written all of the film’s songs with Sonny Burke, in addition to voicing a number of the characters, including a Pekingese named after her, Peg, who sings the song “He’s a Tramp.” Peggy contended that she wasn’t being properly compensated for the VHS release. “I think it’s shameful that artists can’t share financially from the success of their work,” she told the New York Times at the time. “That’s the only way we can make our living.”

She would eventually win her case, which established new standards for how artists would be compensated for such releases in the future. It just might be the most important part of her legacy; something that will benefit performing artists for years to come. Yet a lawsuit is probably not the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Peggy Lee. You’re more like to think of the songs she’s most associated with, which, in addition to those Lady and the Tramp numbers, include “I’m a Woman,” “Is That All there Is?” and, of course, “Fever.” But again — how many people know that Lee not only wrote new lyrics for “Fever,” she was also responsible for its distinctive arrangement?

One could say that in spite of all her achievements — the hit records and films, the sold out tours, the awards and honors — the full breadth of Peggy Lee’s accomplishments has tended to be overlooked. Look to some new releases and events this year to offer a fresh perspective. The concert “Tribute to Peggy Lee and Frank Sinatra,” set for July 27 at the Hollywood Bowl, matches the timeless work of these two iconic artists with performers like Billie Eilish, Bettye LaVette, Seth MacFarlane, and Debbie Harry, among others, backed by the Count Basie Orchestra. LA’s GRAMMY Museum in Los Angeles is currently hosting the exhibit “100 Years of Peggy Lee,” running through September 5, featuring a wealth of personal items, including Lee’s paintings and drawings, scrapbook clippings, and her fabulous jewelry collection. Finally, there’s the reissue of Miss Peggy Lee: An Autobiography in an expanded edition that updates Lee’s story since the book’s first publication in 1987 (in the UK; US publication followed in 1989).

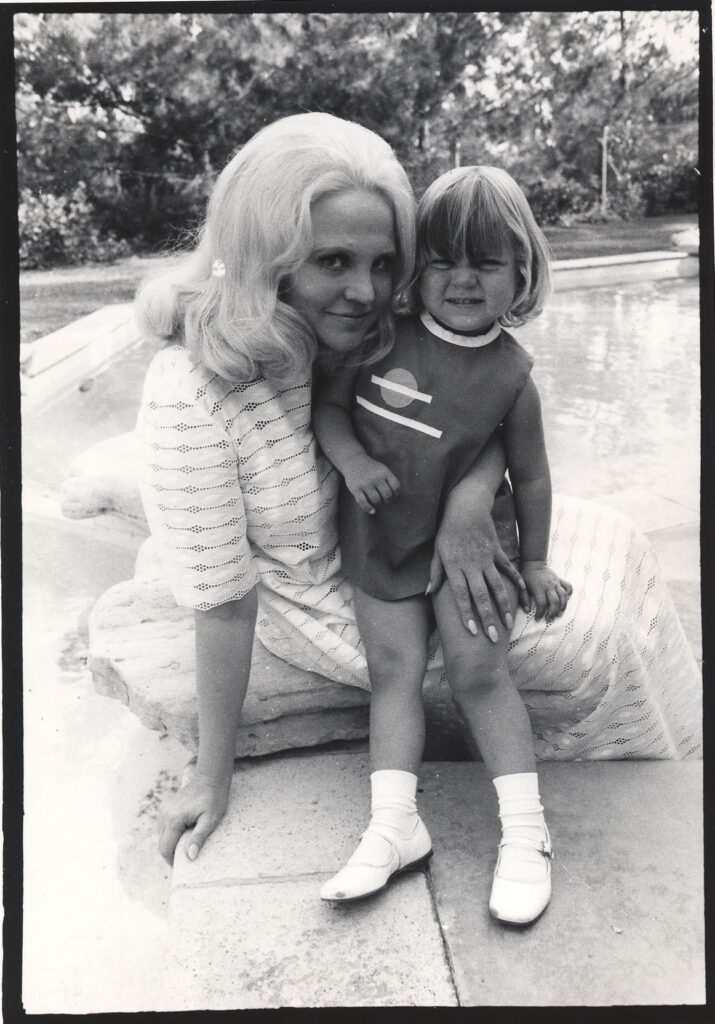

Overseeing all this is Holly Foster Wells, Lee’s granddaughter and president of Peggy Lee Associates. “I always kind of laugh at that title of ‘president,’ because really the title is ‘granddaughter,’” she says. It’s a job she began preparing for as a child, when she began traveling with her grandmother, laying out her makeup before shows and keeping her company backstage or in the recording studio. Now she works to keep Peggy Lee’s music alive for subsequent generations, overseeing record releases, licensing deals, publishing, and keeping up with new developments in communications, like streaming and social media.

“My grandmother told me when I was six years old that I was going to be doing this job,” she says. “I didn’t understand it; I didn’t even know what she was talking about. And as I got older she started giving me little nuggets of information along the way; my whole childhood growing up, she was teaching me what she wanted. And what I did understand was that her music was so important. And the fact that she was entrusting it to me felt amazing; I mean, that she would trust me that much. She had a lot of business people around her, but she wanted to know that someone who knew her and understood her and cared about her would keep it going in the way that she created it. So I think that’s why she picked me, because I was her flesh and blood, and a lot like her. She trained me.”

Lee loved keeping her family close, though her own upbringing had been difficult. Born Norma Delores Egstrom on May 26, 1920, she grew up in rural North Dakota; the former train depot where her father worked in Wimbledon is now a museum with a permanent Peggy Lee exhibit. Her mother died when she was four, and her stepmother proved to be monstrously abusive. The music on the radio and the glamourous worlds seen in the movies provided a mental escape before she could engineer a physical one.

She started out singing with a local dance band, and performed extensively on radio; it was during her time on the air at WDAY that she was rechristened “Peggy Lee.” There were subsequently trips to California, where she worked variously as a waitress and a carnival barker while gaining a foothold in area clubs and eventually performing more widely. While performing at the Buttery Room at the Ambassador Hotel West in Chicago, she was spotted by Benny Goodman, who hired her as the “girl singer” for the Benny Goodman Orchestra in 1941.

Her first recording with the Orchestra, “Elmer’s Tune,” was released soon after, a lively number with the kind of lyrics (“What makes a lady of eighty go out on the loose?”) that matched Lee’s own playful sent of humor. After a rough start with the critics (one photo of her was captioned “Sweet sixteen and will never be missed”), the hits began to arrive the following year. Following her marriage to Benny Goodman Orchestra guitarist Dave Barbour in 1943, she tried to quit show business — “tried,” because offers of work continued to come in. With the encouragement of her husband (who thought she may regret not taking advantage of the opportunities before her) she signed with Capitol Records, as well as developing a new talent: songwriting.

It was an atypical move for the era. “Back then, there were not singer-songwriters,” Wells explains. “There were songwriters and there were singers. So it was really unusual that she was doing this. That has been one of my missions, talking about her songwriting and how she was one of the first contemporary female — or not even female, just one of the first singer-songwriters. And she then had the foresight to start her own publishing company, which is the company that I run to this day. She had a head for business on top of being an artist, which is kind of unusual.”

Peggy’s first collaborator was Barbour. “I Don’t Know Enough About You” is a teasing tune about trying to figure out one’s partner (in the promo film, Peggy looks like she’s interviewing a job applicant). “It’s a Good Day” makes something as mundane as paying your bills sound like lots of fun. “Golden Earrings” was the hit song for the film of the same name, and she went on to provide songs for such films as Johnny Guitar (the only Western to star Joan Crawford), Anatomy of a Murder, and the Russians are Coming! The Russians are Coming! Over the years, she collaborated on songs with such notable names as Duke Ellington, Quincy Jones, Cy Coleman, and Harold Arlen.

“She wrote around 270 songs,” says Wells. “And I keep finding more, so that number just keeps going up. It’s kind of crazy, because I just keep going through boxes of things and I’ll find lyrics. And then I go through tapes that she made and I find demos that she’s recorded. It’s really astounding, but I have learned not to be surprised.” Given that only 1989’s The Peggy Lee Songbook: There’ll Be Another Spring focused on Lee’s songs (and a mere thirteen of them at that), a collection devoted to her songwriting seems long overdue.

In addition to her songs, Peggy also wrote poetry, and the updated autobiography features all the poems that appeared in her book Softly — With Feeling: A Collection of Verse by Peggy Lee, which she had privately published in 1953 (the title refers to her understated style of singing). The poems of nature and relationships reveal Lee’s more contemplative side; it would’ve been wonderful if she’d done a recording of, say “For People Who Are Not Sentimental,” an extraordinary look at how childhood disappointments lead people to build emotional walls around themselves.

Wells’ favorite is an untitled piece that begins, “I give my will to life and let it live me/All my mistakes to love/Love will forgive me…” “It says so much about her,” she says. “This shows her spiritual side and really what she believed; she was always telling me to let things go, turn things over to a higher power, or the universe. She was always talking about the light. When you think something negative, she would say, ‘Don’t give power to that; send white light to that thought.’ She was very much about positive thinking. She had a lot of hardship in her life. A lot of hardship. And back in the day, you didn’t go to therapy and go to rehab or workshops and work through your trauma. So her outlet was poetry, songwriting, music, singing, and spirituality.”

Lee didn’t write “Fever,” but her final touches shaped it into a classic. Written by Eddie Cooley and Otis Blackwell (under the pseudonym John Davenport), the song was originally recorded by Little Willie John in 1956. Whereas that version is an uptempo blues with a decided swing, Lee chose to make her own version, released in 1958, a study in minimalism, insisting on having only bass, light percussion, and finger snaps backing her, the better to highlight her “softly with feeling” delivery. She also wrote new lyrics for the song.

Yet not only did she receive no credit for being a lyricist, the song’s Grammy Award nomination for Best Arrangement credited the session’s orchestrator, Jack Marshall, and not Lee (“Fever” was also nominated for Best Female Vocal Performance and Record of the Year). Capitol Records executives told her not to make a fuss about it; did she want to be seen as a troublemaker? So Lee kept quiet — then.

But she didn’t hesitate to push back just over a decade later, when the songwriting team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller brought her “Is That All There Is?” The song is a meditation on the meaning of existence, with the narrator left unmoved by a series of life events: the tragedy of a house fire, the antics at the circus, the sorrow of heartbreak, even the inevitability of death itself. “If that’s all there is, let’s keep on dancing,” the song concludes with a weary sigh, “Let’s break out the booze and have a ball….”

“I will kill you if you give this song to anyone but me,” Lee told the songwriters. “This is my song. This is the story of my life.” Leiber and Stoller were agreeable, but Lee’s memoir recalls “resistance everywhere” about her recording the song, which was seen as too much of a downer. Even after its recording, the label didn’t want to release it. Lee finally forced Capitol’s hand when she promised to make an arranged television appearance if the label agreed to release the song. Lee had the last laugh; “Is That All There Is?” became her first Top 20 twenty hit since “Fever.” And she also won her own Grammy for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance.

Peggy Lee was proud of her work and no longer hesitated to speak up if she felt she wasn’t getting her due. She’d been happy to help promote The Lady and the Tramp when it was reissued in the 1980s. “She imagined that she would be getting a nice big royalty check, because here was this new way that people could see old films,” Wells explains. “And when they didn’t give her the royalty check, and she saw how much money they made, she was furious — not just for herself, but for other artists, because she just felt that artists should be paid for their contribution. And by that time in her life, let me tell you, she was a strong woman, and there was no part of her that was going to be quiet. So she was not at all afraid to sue.

“It was a very intimidating situation and it took years and it was intense and grueling,” she continues. “But I never saw her be meek or worried. She was just, ‘This is wrong, and I need to fix it.’ The one thing I did see is it took a huge toll on her health. She was not in the best of health at that time, and it was a lot of meetings, and depositions, and it went on for years and years. And then it went to trial. And for her to get up every day, looking like a star and getting to downtown LA was a huge effort. And I went with her to court several times. It was hard on her. But she was so proud when she won and again, not just for her, but for all artists. It was a precedent setting case. And so she was really proud of that, that she had fought for the rights of other artists and really redefined home video rights. And when you see certain language in contracts now, it stems back to that case, about technology now created or created in the future.”

After spending her childhood accompanying her grandmother as she worked, Wells took some time off when she was in her late teens. “I told her that I didn’t want to work for her anymore; I just wanted to be her granddaughter. I felt like I needed to do my own thing. She said she understood, but that she just needed to know that I would look after her affairs when she was gone. And I said, ‘Absolutely, I promise you.’ It really mattered to her.” Wells pursued a career in television, until signing on at Peggy Lee Associates in the late 1990s. By then, Lee had stopped performing, and she’d released her last new album in 1993. But there were always projects to oversee, like new compilation and box set releases or organizing her voluminous archives.

Peggy Lee died in 2002, at the age of 81. “When she died, I will never forget walking through her house and thinking, ‘What am I going to do with all this?’” says Wells. “It was overwhelming. I’m still sorting through all her things.” Among the many boxes, she found a number of timelines her grandmother had put together of her life and career, one in particular singled out with a note, “Most Important Timeline — Save!” “I was amazed,” Wells recalls. “Like, who is she saying this to? And it was all in caps, typed. And then she had handwritten something on the top of it, like ‘Save!’ And it was in plastic. I swear to you, when I go through these boxes sometimes, I feel like she’s left me a treasure map. It’s like breadcrumbs that she’s left in the forest that I’m following. Like she knew that I would probably be the one that would be looking through all of this, and that she wouldn’t be here to tell me certain things. And she left me all of these notes and signs and recordings and it blows my mind every time. And, you know, even though I’m running a business, this is my grandmother. So it’s very personal to me. And I sometimes have to stop and just breathe and think. I cry. I’m grateful. It’s like, wow. And I wish I could ask her things now that I just didn’t have the foresight to do back then.”

Along with the records and the licensing deals, other Lee-related projects are currently on what Wells calls “my Peggy Lee bucket list:” a coffee table book, a documentary, and a feature film, set to star Michelle Williams and directed by Todd Haynes. Peggy Lee has proved to be the kind of legacy artist whose work is constantly being rediscovered, as when the use of her 1949 song “Similau (See-Me-Lo)” in a commercial for Samsung’s Galaxy Note 8 phone led to its unexpected appearance in Billboard’s Jazz Digital Song Sales chart. And now Wells is the one telling her own sons that they’ll be carrying on that legacy.

“I’ve explained to both of them, ‘So, when I’m gone, you will be the keepers of the flame.’ I’m starting to look to at, what happens when I’m not here? Because it’s going to live on beyond me, and the next generation doesn’t have that direct connection to her. So I now feel this responsibility to keep it going. I’m getting the stories out so that they don’t go with me.”

Follow Peggy Lee on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook for ongoing updates.