“A lot of the goal with my art is to eradicate this idea of homogeneity, of Black people all experiencing and feeling the same thing,” says Shara Lunon, NYC-based multidisciplinary artist and one of the winners of the 2022-23 Audiofemme Agenda Grant. “I’m starting to think all the pieces really focus around the feelings that I felt in particular, and it’s not necessarily how all Black people felt, but just specifically how I felt in my environment.”

Lunon is a Black, Jewish and queer improviser, poet, vocalist and composer. She grew up splitting her time between Florida and New York, where she moved full time to pursue and complete a graduate degree in Performance and Composition at the New School this past year. In her artist statement, she refers to herself as “the product of a culture deferred – a simultaneous mixture of erasure and mutation,” her ethnic identity split between two historically oppressed communities, though as she clarified in an interview with me, “There are different cultural references that I have, but… it’s kind of the same in the sense that if you’re Black, you’re Black.”

She is hard at work on “Bitter Fruits,” a multiform song cycle created in response to what cultivated the “Freedom Summer” of 2020, and the triggering of intergenerational trauma that surfaces when viewing a lynching. She says it is the largest piece she has written to date, examining the idea of what Black people “are” or “should be,” something not only forced upon her but something she has strived to be as a multi-racial individual. She explains that “what ‘I should be’ and how I felt has always lived in conflict.”

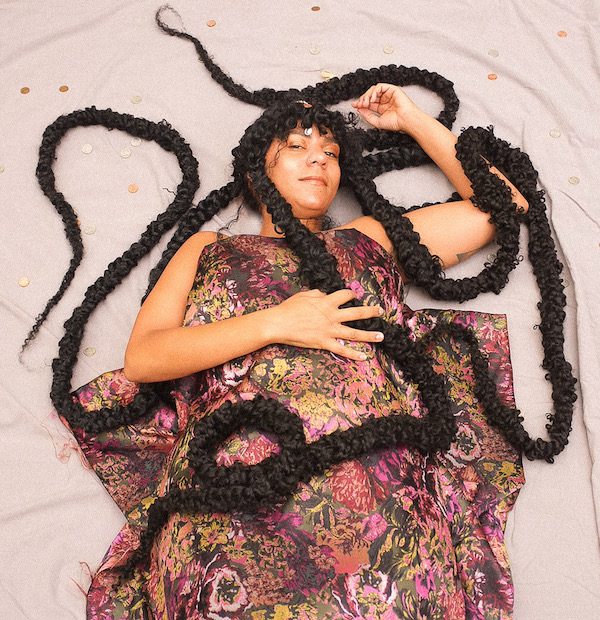

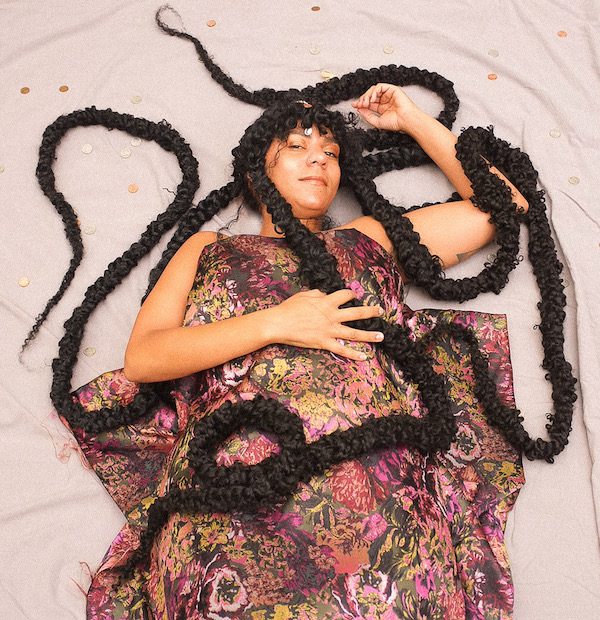

The piece features a wig of ten-foot braids that encase wiring, programming of photocells that change sound patterns between pieces, and choreography. While hair is an integral and oftentimes emotionally fraught aspect of the Black female identity, she digs deeper here, explaining that hair – and braids in particular – “has been used as coded language, for maps for people to escape from slavery, or to hide food within it. So I feel like the braids became this secondary way of communicating, not just through my voice, not through the sounds that are coming out of it, but also a representation of Black culture and history, and to transmit other messages of solidarity and pride in my cultural history.”

In other words, it’s a vehicle in which to speak her truth without having to explicitly explain, an emotional labor the Black community has been tasked with since time immemorial but particularly in the racial reckoning that occurred in the wake of the George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery murders of 2020. For many white allies, particularly those too young to have lived through the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, this was a moment of realization of the trauma people of color have lived with for generations, leading to a sudden burst of energy and activism that many BIPOC knew couldn’t be sustained. But while white allies could relax back into their identities once the burst of energy fizzled out, Black people remain Black, and must continue to deal with these multi-generational traumas and issues whether they want to or not. Watching white friends and colleagues wake up on Instagram or in the streets for a few months and then retreat back into the ordinary was an isolating experience.

Lunon explains that the piece has “less to do with the protests, and more to do with the feeling of understanding what an ally could actually mean and those feelings of isolation or sadness. They’re very deep and generational, and combined with this very ‘in the moment’ mission of the allies that for me was like, I will already see the end date before people want to realize.” She says the work is “very reactionary, in the moment and organic to the space that I’m infusing the technology outside of the machine itself. I’ve been building my own little tiny embroidered oscillators. I like the way it responds to motion.”

Her practices “parallel my focus on the Black individual, as a way to negate the narrative of the homogeneity of my people – we are all having a human experience.” No one’s art should be limited in theme to their identity, and neither is Lunon’s. While we wait with anticipation for her to unveil her “Bitter Fruits,” she premieres “Sankofa” this weekend at the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens’ Biophony, a walkabout listening experience conceived by the Grammy-nominated collective Metropolis Ensemble. This will feature more than twenty groupings of musicians stationed throughout the gardens to perform fifteen new works of music inspired by birds.

Shara Lunon contains multitudes, more than can ever be encompassed in identity descriptors like Black, Jewish or queer. Even when the work deals explicitly in these themes, the medium is always the message.

Follow Shara Lunon on Instagram and Facebook for ongoing updates.