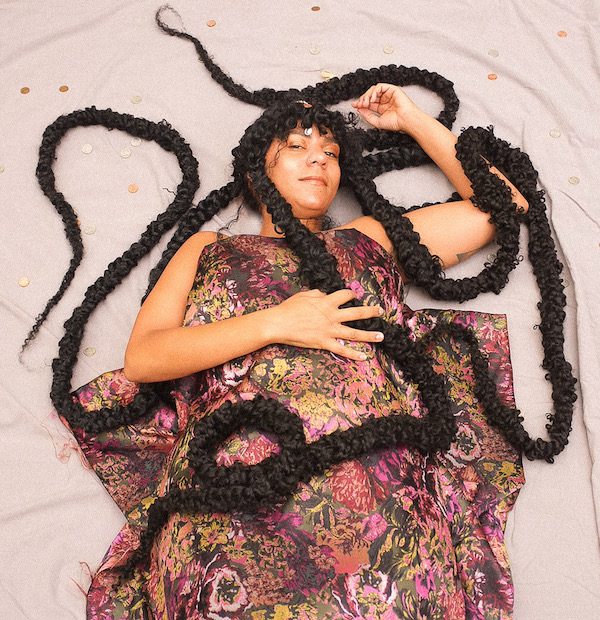

When’s the last time you considered your relationship to the land you live on? For those of us living in cities, it can feel particularly challenging to cultivate a connection with the natural world, given that in our context it’s been largely paved over. But to Brookyn-based artist and musician Jennae Santos, who creates under the moniker W.S.A.B.I., our urban setting is all the more reason to consider this question.

To Santos, there’s something radical and subversive about communing with the natural world on a more intimate level. W.S.A.B.I. itself stands for Warped Sanggot And Boss Interior, which she describes more specifically in an artist statement: “The Sanggot is a Visayan Philippine hand sickle— a farming tool and martial arts weapon that guides W.S.A.B.I.’s artistic, political, and emotional practice in the harvest of love, community, and subsistence, and the fight for the oppressed body. Our blade is warped from the ongoing work at hand: decolonization, abolition, and warrior pedagogy, fight songs against white supremacist patriarchal capitalism, love songs stoked in multi-sensory radical commitment. Boss Interior means inner strength through the work, and acknowledgment of both the oppressor and the spirit of resistance within colonized identity.”

Santos’ musical style is highly technical and at times jarring, a genre she’s come to define as “art prog.” And by that, she means to synthesize the angular, sometimes unpredictable acuity of art rock with the ambitious composition and repetition of progressive rock. Her most recent release is the Three Houses (Live) EP. Attributed to the WSABI Duo of Love featuring Alex Goldberg, live from quarantine, the three songs were written and recorded over what she describes on her website as “transient overhauls” at three different houses over the course of the initial COVID lockdown. Minimal and lacking the jolting angularity of her work with a full band, they reflect her newfound experimentation with field recordings that led to the walking mixtape, though they do have their heavier moments.

Like many musicians, her practice became more of a solo endeavor when COVID separated her from her bandmates, and her creations became more experimental. A winner of Audiofemme‘s 2020 Agenda Artist Grant, she took the opportunity to expand her artistic acumen to something new and different: a “walking mixtape” exploring the concept of harvest, made in collaboration with Red Hook Farms, where she is a CSA member and volunteer.

She took field recordings to include sounds from the farm, plant meditations and personal accounts from the youth farmers she supervises – many of whom are neighborhood teens with little existing connection to the natural world – and converted the sound samples into beats inspired by the energy of the farm, creating a site-specific musical walking tour that visitors could access by scanning a QR code at the Saturday farmer’s market.

“I have like 200 recordings on my voice memos,” Santos shares when I ask how she takes these field recordings. They require nothing more than an iPhone, allowing Santos to record sounds whenever inspiration strikes: for example, for a recent commissioned piece on climate change, she went out to Far Rockaway and Dead Horse Bay to document the sound of tiny bits of glass washing in on the tide.

Santos began volunteering on the farm as part of her CSA membership, the first time she had ever harvested her own food, and found the practice grounding. She took to studying the larger socio-economic issue of food insecurity over the pandemic and became all the more inspired.

“It’s such a global issue, food insecurity, and the rights of farmers, from migrant farmers to just people of color having food sovereignty and land sovereignty, so combining that with my artistic passions has been something I’ve been trying to work on for the past year,” she explains. “It’s coming from this wanting to see how we can inform each other, and land is such an experiential element that a lot of humans in cities seem to forget, especially if you’re not having to grow food for yourself.”

Issues of food insecurity and the inaccessibility of fresh produce to underprivileged neighborhoods have always plagued major cities, and New York City is no exception. Even when you have the privilege of affording fresh foods, the hustle of living and surviving in a major city can often leave you reaching for whatever foods are the fastest and most accessible, regardless of how unhealthy or processed they might be.

“I’m trying to bridge those practices of taking time to connect to food and to your health and well-being, through land, and I think that art is an access point for that, if not food itself,” she says. “What I was saying before in terms of land being very experiential, sound is also very experiential. Both of those elements really inform the human condition and remind us that we’re not just machines in an economy, we’re animals — we’re humans of the earth.”

As a self-described “decolonizing Filipinx,” Santos found great inspiration in the agricultural heritage of the Philippines, particularly a rice winnowing song recording from the Kalinga mountain province, and folk dancing based on different baranguays’ (the native Filipino word for village, or district) agricultural specialties and goods. She notes that there has always been a sacred relationship between art and nature in pre-colonial cultures, something she hopes to revive in her own contemporary community of Red Hook, Brooklyn. She conceptualized the project from her own moral exhaustion with the capitalist commodification of both the music and food industries, hoping that she might begin to heal both by synthesizing them with an immersive experience.

By thinking so critically about these issues, Santos has led others to reevaluate their relationship to the land they live on, namely the youth farmers she works with. She references Braiding Sweetgrass by scientist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer, how “finding your own indigeneity is about getting to know the land you inhabit.” Her exercises ask the youth farmers to consider their relationships to art and land, and encourage them to explore their ancestral agricultural heritage by asking elder family members about the family’s historical relationship with land. This aims to undo some of the damage wrought by capitalism and colonialism, particularly the way the latter can limit the depths of ancestral knowledge for people of color. Ultimately, though, it’s meant to unify, a reiteration of Santos’s earlier point, that “we are humans of the earth,” which she does in part by recording these exercises with the youth farmers and incorporating them into the mixtape.

“It’s supposed to evoke a sense of grounding and wonder, as it relates to land, especially in an urban environment, [where] we tend to lose that sense. We have to venture out to go hiking, out of the city, when it really is all around us, so it’s meant to be a reminder of the importance of city ecology also,” she explains, describing the interesting juxtaposition in her field recordings of construction sounds coming from the Amazon distribution warehouses across the street from the farm with its own lush, peaceful sounds. She takes this vast array of sounds and imports into her drum kit and uses them to create the beats that accompany the other sonic elements of the mixtape.

“There’s a pulse to the city, especially when there’s construction nearby. There’s a rhythm to the different seasons, and life cycles of plants,” she continues, explaining how this rhythm is aesthetically similar to the guitar loop-laden durational pieces she typically works on. The repetition in these pieces, she says, makes you “feel time differently.”

“I think I’m trying to bring that type of patience, that kind of patience [that] also happens when you’re on the farm, just the way that people interact with each other and the space that’s there. It just feels like time, the New York hustle, slows down a bunch, and is more present with this newer rhythm, which is vastly different than just navigating the city.”

While the pandemic has forced all of us to slow down in one way or another, the mindfulness and intentionality Santos brings to her Red Hook Farms project is very welcome as society slowly circles back to whatever version of the status quo will remain in the wake of our present turmoil. Many of us don’t want to go back to the way things were before, rushing through our days as we juggled a seemingly endless cycle of jobs, tasks and errands.

Santos does want to return to normal in the sense that she misses playing with other musicians. On October 28, she’ll participate in a performance dubbed “The Great Rat Summoning” at the Sultan Room, with EVOLFO, Castle Rat, Reverand Mother, and DJ Miss Hap Selam. She’s also heading into the studio with a full band to record the first full length record for the W.S.A.B.I. project, but her connection to the natural world remains; she participated in a harvest ritual at O+ Positive Festival in Kingston, NY earlier this month. I’d imagine that once you hear the rhythm of the natural world around you, it’s difficult to unhear it.

Follow W.S.A.B.I. on Instagram for ongoing updates.