It all began with a post on Tumblr.

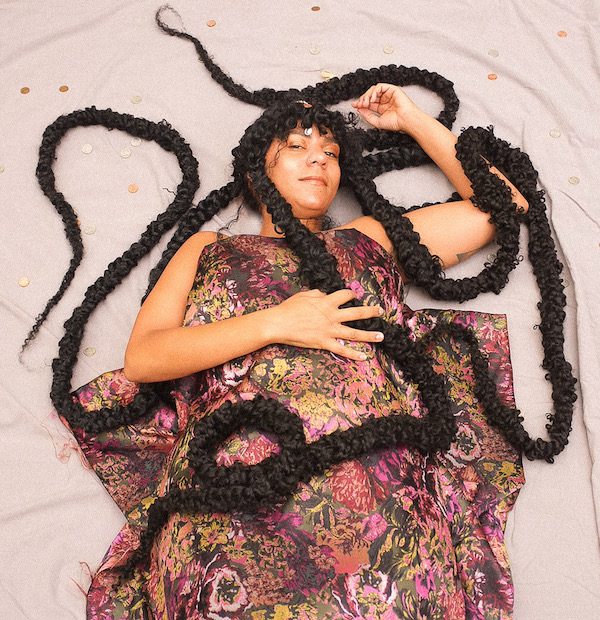

“Medusa was defending herself,” explains Medusa, a Buffalo-based trans-nonbinary, intersex music producer and visual artist and winner of the Audiofemme Agenda Grant, about how they got their name. “And then I read the things that people were saying in the notes about how Medusa was attacked by Poseidon and then demonized and turned into a monster and then banished from the place that she had called home for her entire life, and I was like, this is very familiar.”

Medusa came to the Greek myth by way of isolation. After being stalked on campus at their university, many of their friends felt they were making the whole thing up. They delved into the internet and started tinkering with Audacity, the early manifestations of their present musical practice.

With their grant, Medusa is producing a short film to accompany an upcoming concept album entitled Allegory of the G/Rave, a queer retelling of the story of Medusa. They latch on to those themes of isolation and self-protection in terms of the queer experience – by chronicling Medusa’s life, transformation and persecution, Medusa intends to contribute to the emotional needs of of their young divergent audience, and to galvanize their self-worth, providing them with the representation necessary for self-actualization.

When they started playing music, they had never even been to a show. “I didn’t know what an XLR cable was,” they say. “I played with the EQ on my computer while my music played. And then sometimes I talked when I was brave enough to talk over the music, and then that was my first show, and then it just sort of snowballed, and it turned into this community, this melding of my own self-discovery and the connection with my community.”

Medusa’s birth as a musician came with their realizations that they were both queer and intersex, things they found out very publicly because they were making music about them. “That brought me more community than I ever lost in the first place. Which is and has been the biggest – I don’t know if I should say blessing, but I’ve been very lucky.”

That they hone in on this myth while adopting the moniker Medusa adds layers to the narrative, particularly given that their musical practice is driven so organically by emotion. “Auditorily it’s not quite what people call synaesthesia, but when a song is stuck in your head and affects your mood,” they explain. “That’s how it happens for me but backwards, writing. So when I’m having an emotion, I’ll hear music, not necessarily in a hallucinatory way, but the urge to translate that into actual tangible, audible sound.”

They call them “transmissions” – when they’re “having a feeling or realizing that in the background of my mind, there’s been a song playing the whole time that I have to then go check to see if it’s real, and it exists and it’s stuck in my head, or if I’m writing subconsciously because of the feeling that I’m having. And then I’ll run over to the computer and I’ll get it down…I’ll figure out oh, what song does my subconscious want that to go in?”

In that way, they update the myth for the community they have built online, imparting a certain wisdom that while being different may be off-putting to some, it’s actually a source of power, a means of self-protection if harnessed well. And because they learned it the hard way, Medusa seeks to pay it forward with this narrative film of the concept album, split into eight music videos that will run a total of thirty minutes.

“The story of Medusa being something that she didn’t ask to be transformed into, something that she didn’t want to be necessarily, and then turning into that was very relatable for me. Because after that point, you start to harness it. In an effort to protect yourself, you are different,” they say. “Do I have to be alone forever? What does the process of re-opening yourself up look like, and is it even possible? So this has been a big process of self-discovery, but translating that in a way that is useful to other queer people is not just comforting, but also inspiring.”

Follow Medusa on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for ongoing updates.