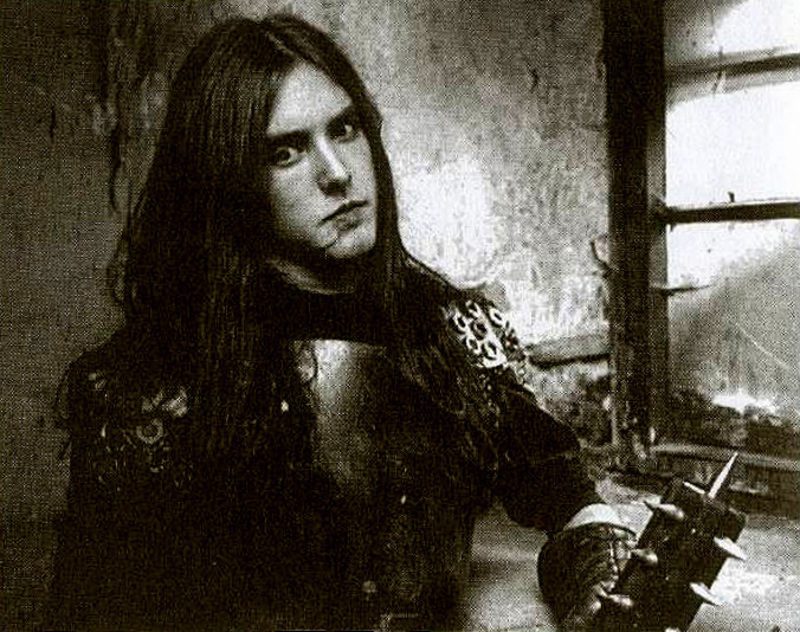

Shortly after Irish black metal outfit Altar of Plagues announced their breakup last summer, the group’s frontman James Kelly unveiled the first glimmers of a forthcoming album to come from his electronic side project WIFE. I–along with pretty much all the metal fans I know–wasn’t ready to be consoled. Altar of Plagues’ disbanding came on the heels of their third and best studio release Teethed Glory and Injury, an album that I loved for its ability to deconstruct and rework the music’s sludgy layers, its clipped, nightmarish, often waltz-time beats, and the near-visual landscape created by the album’s texture and subtle details. WIFE, on the other hand, was a kind of spacey electro-pop endeavor–no more metal. Was Kelly just being a contrarian? Was he trying to show off his eclectic musical range? Was he simply quitting while he was ahead?

Maybe, but a listen to WIFE’s new album What’s Between, which came out June 9th on Tri Angle, goes a long way toward elucidating the jump between Kelly’s work with Plagues and where he is now. From the first track, “Like Chrome,” What’s Between demonstrates a lot of restraint. It’s an establishing shot that takes its time in developing, expunging any other thoughts and sounds that may be rolling around a listener’s head, effectively clearing a space for the music to come.

That music is strange–slightly dystopian, slightly doom-y–and though I would not call the collection optimistic, Kelly finds a way to develop a sense of wonder, awe, and curiosity as a result of the spaciousness he creates. Even the scary songs, like “Tongue,” get their spookiness from suspense. If an Altar of Plagues album were a horror film, What’s Between would be a psychological thriller. “Tongue” uses every sound at its disposal, shaking and rattling twitchily, like a monster waking up from hibernation and flexing all ten of its talons. That said, the music’s aggression remains implicit, and at no point dominates the album.

The nine songs on this album run about average length, varying from two and a half up to just over seven minutes, but often feel as if they’re on the long side. Many of the tracks, especially “Tongue” and “Heart Is A Far Light,” contain several moods. A poppy and playful couple of minutes give way to larger dreamscapes or house-like heartbeat rhythms. It’s not as if Kelly was ever a conventional black metal musician, but those looking for something to put up the horns to will find it, sort of at least, in “Salvage,” whose distinct and aggressive beat hearkens back to the pounding three-four rhythms of Teethed Glory songs like “God Alone.”

Now that I’ve listened to the album, this observation sounds like it should have been obvious from the beginning, but Kelly’s fixations and devices aren’t all that different as an electronic musician than they were when he was making metal. The album–like the first two Plagues albums, White Tomb and Mammal–runs a little introverted, more interested in developing its themes than in engaging the listener. To be fair, it took three albums to make Teethed Glory. It seems like Kelly could have chosen any aesthetic–metal, electronic, pop, or any other–and go about making music in a similar way: he builds a minimal foundation and expands to fill the space between the walls he’s erected. In the case of Altar of Plagues, Kelly followed the black metal thread until he was satisfied he’d reached the end of the line, and then he moved on. If What’s Between isn’t a perfectly realized electronic pop album, that probably means that WIFE’s not done yet.

Listen to the eerie “Tongue,” off What’s Between, below via SoundCloud. What’s Between is out now on LP, CD and digital release via Tri Angle. Get it here!