Scandinavian black metal began as direct descendant of English heavy metal acts like Venom and Bathory, the morbid younger sister of death metal and the spacey, supernatural cousin of hardcore punk. It’s a young subgenre—Mayhem’s 1987 Deathcrush EP sparked the scene in Norway in the late eighties and early nineties, and by the end of that decade, black metal had largely self-destructed. The movement adopted heavy metal lyrical styles towards darker, more occult themes, emphasizing a theatrical live show style in which musicians would perform wearing corpse paint—a more realistic take on Kiss-style stage makeup—and sometimes cut themselves on stage, carrying animal heads on sticks or flinging meat and blood into the audience. Many bands identified as Satanist, either symbolically or in practice, for shock value or in response to the mildly Lutheran Scandinavian norm. This led to a series of church burnings throughout the nineties, many of them nominally in protest of Christian churches built on top of ancient Pagan burial grounds. What began as a game of one-upmanship amongst the heavy hitters of the scene spiraled symbolic Satanism into real acts, and several of the genre’s most talented musicians’ careers were cut short by suicide, murder, prison, or alienation from the ever-increasingly extreme ideology of the movement.

Scandinavian black metal began as direct descendant of English heavy metal acts like Venom and Bathory, the morbid younger sister of death metal and the spacey, supernatural cousin of hardcore punk. It’s a young subgenre—Mayhem’s 1987 Deathcrush EP sparked the scene in Norway in the late eighties and early nineties, and by the end of that decade, black metal had largely self-destructed. The movement adopted heavy metal lyrical styles towards darker, more occult themes, emphasizing a theatrical live show style in which musicians would perform wearing corpse paint—a more realistic take on Kiss-style stage makeup—and sometimes cut themselves on stage, carrying animal heads on sticks or flinging meat and blood into the audience. Many bands identified as Satanist, either symbolically or in practice, for shock value or in response to the mildly Lutheran Scandinavian norm. This led to a series of church burnings throughout the nineties, many of them nominally in protest of Christian churches built on top of ancient Pagan burial grounds. What began as a game of one-upmanship amongst the heavy hitters of the scene spiraled symbolic Satanism into real acts, and several of the genre’s most talented musicians’ careers were cut short by suicide, murder, prison, or alienation from the ever-increasingly extreme ideology of the movement.

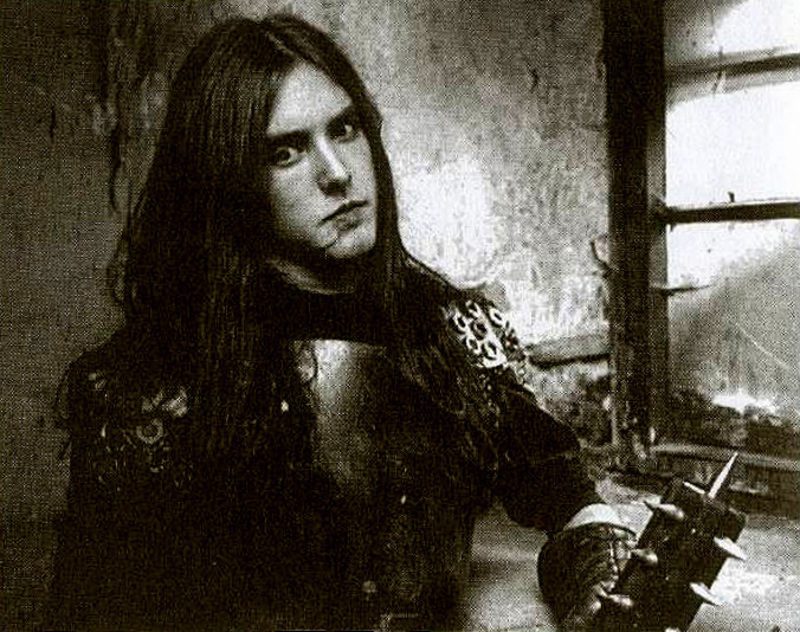

No black metal bands were more prolific than Burzum, a band that put out two albums a year in 1991, 1992, and 1993, and then incrementally slowed its releases(to one every other year or so) after sole member Varg Vikernes was convicted of murdering Mayhem’s frontman, Øystein Aarseth, and incarcerated. Burzum’s Aske album, a three-track mini-LP that clocks in at a scant twenty minutes and came out in 1993, was the last Burzum release before Vikernes’ arrest. Though Aske, in typical nineties metal style, uses thick distortion and rough-edged recording techniques, it also incorporates aggressive bass lines and eighties-influenced power chords that suppress the kind of crackling, rhythmless chaos common in black metal. This actually makes the album accessible, even catchy, compared with contemporaneous releases and Burzum’s later work, which turned ambient and fully electronic while he was in jail and, not having access to an electric guitar, switched to recording on a synthesizer.

Despite strong riffs and an instrumental balance that, although too polished for purists, lent complexity and depth to the record, Aske was underwhelming. This was partially due to its length—the three songs felt like build-up; were it a standard-length album, things would have had plenty of time to get interesting—and partially due to the fact that Burzum valued shock value over musical integrity on this LP. Early in his career, Vikernes expressed his world views in a general sort of way (“Only Transylvanian pussy will do!” reads a Burzum interview conducted by an unknown metal zine, sometime in 1993. “Hail Saddam Hussein! Hail Hitler! Make war, not love!”) However, when the epidemic of church burnings in Norway, beginning around 1992, came to be attributed to Satanist black metal musicians, Varg Vikernes seemed to begin to consider himself more activist than musician. Around the time the Aske album was released, Vikernes was busy giving newspapers anonymous interviews and fending off an arrest for his alleged burning of the Fantoft Stave Church, a prominent, nearly-nine-hundred-year-old cathedral in Bergen, Norway. Vikernes was ultimately found not guilty of that crime, though he was convicted in two other church burning cases, and the album cover for Aske pictured the Fantoft Stave church in flames. Burzum extolled the church burnings in songs and distributed Aske merch, with the same image that appears on the album cover, like t shirts, poster and—you guessed it—lighters.

It’s possible to talk about Burzum’s first two albums without getting into their attending politics. In later releases, Burzum proved more true to political themes than to genre, and has recently released only totally electronic albums. Vikernes divorced himself from black metal long ago, though he helped create it. “Yet again I have left behind the metal genre and have chosen a different path—but for no other reason than me following my Pagan spirit willingly to wherever it takes me,” Vikernes wrote this year in his blog, which I don’t recommend reading unless you want to be deeply offended from about six different angles. Aske follows the musical trajectory laid out by Burzum’s releases, but the shift is clear: this LP is the first of many, many albums the band put out in which the music falls secondary to the message.