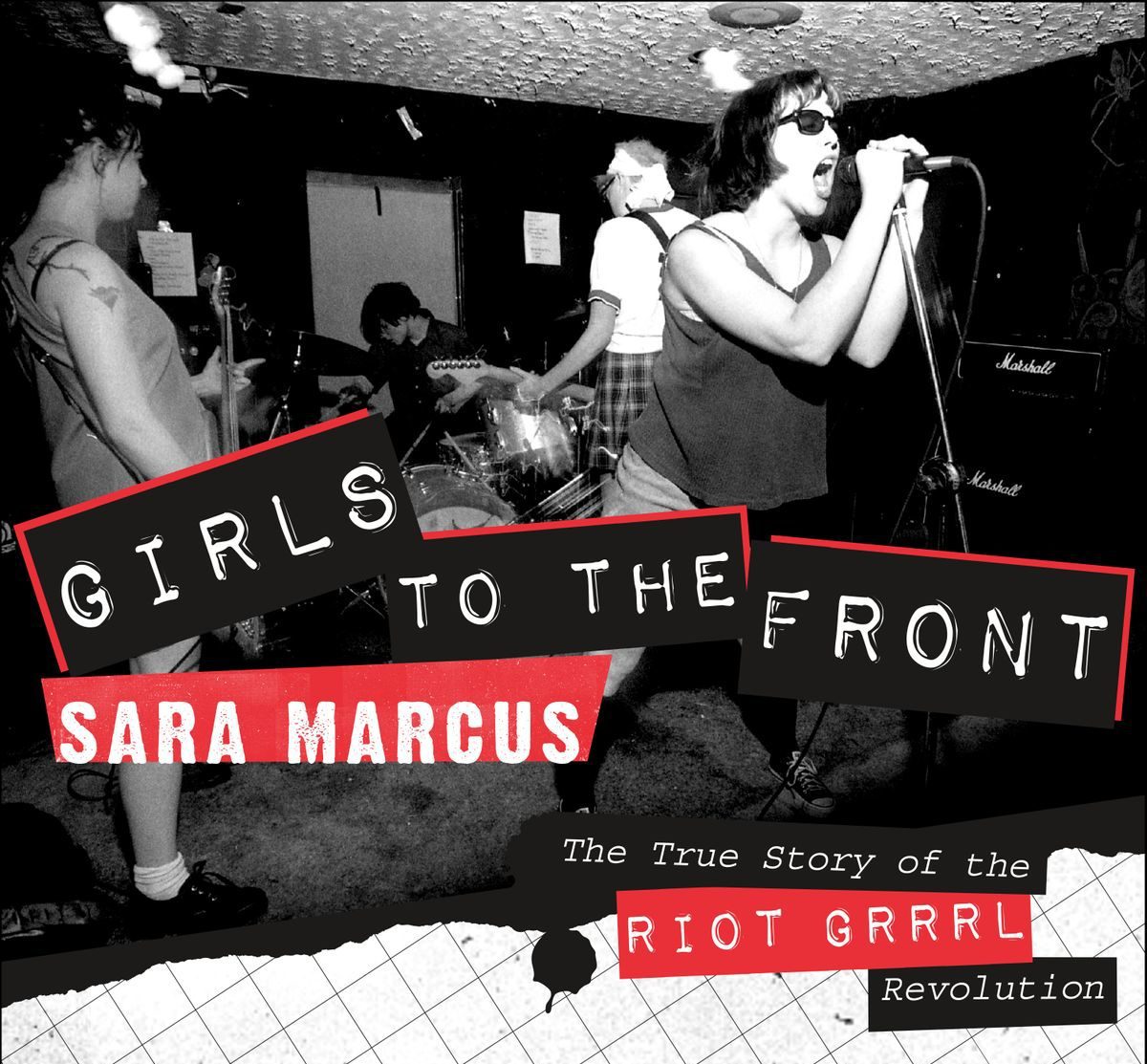

If I hadn’t read Sara Marcus’ Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, I wouldn’t be a rock writer. It was 2013. I had recently graduated art school and was dividing my time between three retail jobs: a liquor store, a grocery store, and a clothing store. One of my friends had recommended it to me, and even though I didn’t think of music as a big part of my identity anymore — something I’d felt pushed out of because I didn’t have the right taste or the correct opinions or the appropriate body of knowledge — I suddenly found myself reading about music a lot.

Maybe it’s because I was hanging out with female DJs. Or I wanted to ably push back when men told me everything that was wrong with what I listened to in break rooms. After four years of honing how my eyes took in information, it’s possible I was trying to improve my ears, too. But when I read Marcus’ 2010 release on long bus rides between cash registers, something in me changed.

Girls to the Front blends passion with criticism, betraying Marcus’ clear love for and intimate experience with riot grrrl while carefully laying out its many skeletons. Male critics love to trot out the feminist punk phenomenon as evidence they remember women play music, too: “I’m not sexist; I’ve heard of Bikini Kill!” But Marcus declares the movement as an important part of music history worthy of critical scrutiny — and hardly a beginning or end point for women in rock. Reading her book turned on a light in me I didn’t realize existed, and made me want to build on her work.

I don’t think I was the only one to react that way, either. In many respects, Girls to the Front anticipated the next 10 years of music books. 2010 to 2019 was a banner time for publishing women writing about rock. And I’m not just saying this as someone who was so inspired by a book about ladies’ sweat-stained expressions of rebellion that I made a slow professional shift; I have the receipts. Not only did this decade give us more women’s stories, but we also witnessed small but meaningful strides in the kinds of stories prioritized (memoirs from the likes of Kim Gordon, Liz Phair, Carrie Brownstein, et al became so ubiquitous they didn’t even fit into this list). What follows is a roving, incomplete list of books — one from each year — that marked small but powerful shifts in the rock ’n’ roll landscape.

2010: Patti Smith’s Just Kids

The 2010 debut from ’70s punk-poet icon set a new standard for memoirs well beyond the rock pantheon. In lyrical prose, Patti Smith describes her relationship with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe — its evolution from friendship to romance to creative wellspring. Even more than a eulogy for one of her most formative friendships, though, it’s a love letter to her influences: Jean Genet, Arthur Rimbaud, William Burroughs, and so on. She gives longform life to Rainer Maira Rilke’s romantic ideas of art as a calling. And because of this title’s wild success — it was a bestseller that garnered numerous awards including the 2010 National Book Award for nonfiction — Just Kids opened the memoir floodgates for everyone from Kim Gordon to Ani DiFranco.

2011: Out of the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music

Ellen Willis is probably best remembered as a feminist cultural critic who touched on everything from decriminalizing drugs to antisemitism on the Left. Somewhat lesser known is that she began her career as a music writer. In 1968, Ellen Willis became the first pop music critic at The New Yorker — the first ever music critic to write for a national audience. Despite influencing writers such as Griel Marcus and Ann Powers, Willis died in 2006 never seeing her music criticism get its due. In this tome, her daughter, Nona Willis Arnowitz, brings together writing that, while very of its time, was a hugely important landmark for music coverage.

2012: Alice Bag’s Violence Girl

Before she was releasing Christmas tracks about punching nazis or clacking away on typewriters alongside Allison Wolfe and Kathleen Hanna, Alice Bag was screaming with The Bags. She first cemented her punk legacy with a cameo in Penelope Spheeris’ Decline of Western Civilization, but Bag has long proven her stay power. In her book, she describes growing up Latinx in L.A.; unlearning the violence she grew up surrounded by; going hip-to-hip and lip-to-lip with both men and women; and how these experiences shaped her life’s work as an activist, educator, and musician. Early L.A. punk was queer and brown, and it had so many women — and Alice Bag will not let you forget.

2013: Evelyn McDonnell’s Queens of Noise: The Real Story of the Runaways

I do a women’s rock history podcast, and my first season is on the Runaways; there may be some heavy bias in this choice. But I’m letting it stand because Evelyn McDonnell has long written about the varied and important ways women have contributed to popular culture, and to me, this is her magnum opus. Queens of Noise provides cultural context while separating fact from fiction for one of rock history’s most storied, undervalued bands. In 2015, the Runaways’ bassist Jackie Fox revealed she was raped by the band’s manager and producer, Kim Fowley. While McDonnell’s book hints at this, she resists outing Fox or even letting Fowley’s predatory, abusive behavior define the band’s legacy. The book is not about what was done to these women; it’s about what these women did for themselves.

2014: Viv Albertine’s Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys.

While Viv Albertine’s memoir tells the story of being an influential musician at the center of 1970s British punk, it’s also an account of everything that comes after that: marriage, motherhood, cancer, divorce — even relearning how to play the guitar. Among other things, Albertine reveals shrinking her musical past to emotionally accommodate her husband and fighting with her publisher to forego a ghostwriter. Thank the stars she won that fight, because her voice is strong, insightful, and intimate. One of the simple elegances of Albertine’s autobiography is how she marks time in a way familiar to so many women and femme music lovers: what she was wearing in that moment, what she was listening to, and who she was dating.

2015: Jessica Hopper’s The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic

When I initially saw this in a bookstore, I actually scoffed. At the time, I was regularly reading so much excellent music criticism from women that my brain couldn’t yet wrap itself around the bold and unfortunate fact of the title. Highlights include Jessica Hopper’s essay on emo (“Where the Girls Aren’t”); Hole fact-checking Wikipedia during an oral history of Live Through This; and an interview with journalist Jim DeRogatis where Hopper unpacks her initial instinct to separate R. Kelly’s art from his abuses and admits that was a mistake.

2016: Laura Jane Grace’s Tranny

Against Me!’s Laura Jane Grace uses diaries entries dating back to the third grade to open up about transitioning, which makes it a landmark trans memoir. But beyond what the book means for transgender visibility, Grace also talks about what led her to punk and anarchism; being part of one of the most celebrated punk bands of the aughts; and reconciling her DIY punk past with finding commercial success — and what it meant when early audiences rejected Against Me! for “selling out.”

2017: Jenn Pelly’s The Raincoats – The Raincoats (33 1/3)

Stories of ’70s heroines really came of age this decade, but so did the critics raised on them. If contributing Pitchfork editor Jenn Pelly’s articles are like singles, here was her first LP. Drawing on glimpses into the Raincoats’ personal archives and using interviews from bands such as Sleater-Kinney and Gang of Four, Pelly provides a tender, collage-like account of the Raincoats’ self-titled debut and how its influence lives on. But perhaps as important as the book was its New York launch party, which bridged multiple generations of music. In attendance was a veritable who’s-who of women in rock, and it led to Bikini Kill’s reunion tour.

2018: Michelle Tea’s Against Memoir

Against Memoir is exactly what the title suggests: it’s not a memoir, but it’s not NOT a memoir, either. Which also to say, it’s not a music book, but it’s not NOT a music book. Some writers observe things like how music is made or who it’s made with; Tea chronicles what happens after it’s heard, sandwiching it between myriad other cultural observations and self reflections. The result is a piecemeal queer history of music that resists historicization. Highlights include her “Transmissions from Camp Trans” — Camp Trans being the trans-inclusive music festival that sprung up across the road from trans-exclusionary Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival — and her history of HAGS, a ’90s San Francisco dyke gang orbited by Tribe 8 who kept bands like L7, Lunachicks, and 7 Year Bitch on heavy rotation.

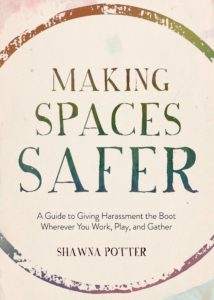

2019: Shawna Potter’s Making Spaces Safer: A Guide to Giving Harassment the Boot

Drawing on over 20 years of experience fronting the hardcore band War on Women, Shawna Potter has been an active voice for improving physical and psychological safety for marginalized people in music spaces. She’s led trainings at large clubs and tiny DIY venues alike, and now she has a book of actionable advice for minimizing and responding to harassment. Potter takes the conversation beyond acknowledging the aggression targeted at so many people in music, especially women and gender-nonconforming people, and declares, “Here’s some things we can do about it.” This, like so many other titles on the list, gives us a glimpse into what the next decade (hopefully) holds: a more inclusive future for women in rock – musicians, fans, and writers alike.