On Saturday, October 26, I attended a San Pedro ceremony. With a group of fellow journeyers, I drank the extract of a psychedelic cactus sourced from Peru, danced around a circle to live music, shook rattles, played drums, lay down to focus on my own insights and visions, and had drug-induced heart-to-hearts with other participants.

The following Saturday, November 2, I went to the HARD Day of the Dead festival in downtown LA. I microdosed some iboga and met others on their own substances of choice, whether that was weed, alcohol, MDMA, or something else. We danced together, sang along to the music, went on our own inner journeys as we swayed to the electronic beats, and talked to one another by the food stands. It struck me how similar this experience was to the one I’d had a week prior.

EDM festivals are modern-day shamanic ceremonies: People use music, dance, and often substances to connect with one another and achieve a higher state of consciousness. With the occasion of the Day of the Dead, which is already full of spiritual rituals meant to connect with ancestors, this association was extra prominent at the HARD Day of the Dead festival.

The afternoon and evening included many diverse manifestations of the EDM genre. Early in the day, Vietnamese-American DJ Softest Hard bound the festival-goers together by inspiring them to sing along to remixes of well-known tunes from Travis Scott’s “SICKO MODE” featuring Drake to t.A.T.u.’s “All the Things She Said.” Then, new-beat producer 1788-L delivered a delightful combination of trappy rhythms and unexpected interludes of classical piano and other instrumentals.

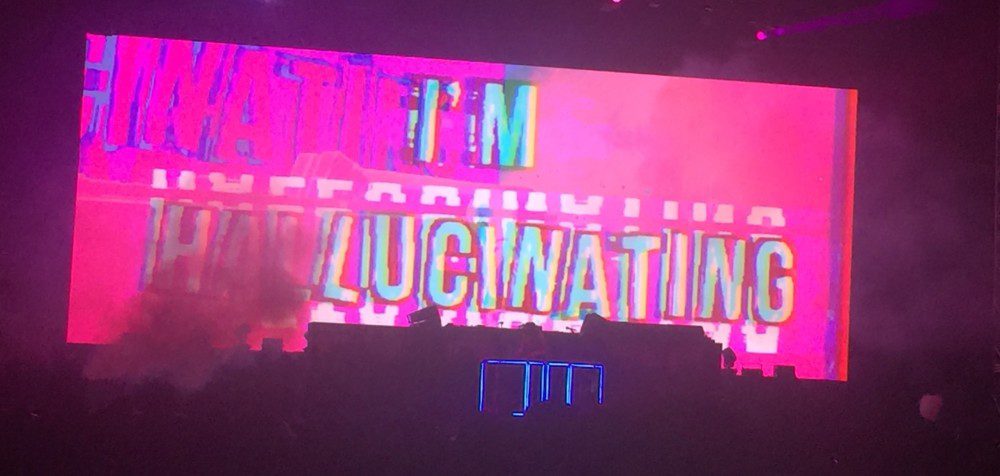

Later on, electropop artist Elohim took the stage for the trippiest set of the evening, with technicolor images of pills and the definition of “hallucination” on the screen behind her. It was during her act that the connection between EDM and psychonautic exploration was made clearest. In “Braindead,” she sings about drugs and spirituality: “All I know is I know what I don’t know / And what I don’t know could fill up a whole bible.” She also played an unexpected and musically fascinating cover of Harvey Danger’s “Flagpole Sitta,” her breathy voice gently drawing out lyrics punchingly shouted in the original.

Another highlight of the evening was Blacklizt, Zhu’s deep house/techno alter ego, who blasted haunting sounds alongside a creepy collection of mannequins in front of a screen showcasing eerie images like scissors. His set reached its climax when he played “Faded (Baby I’m Wasted),” prompting the audience to belt out the lyrics, “Baby I’m wasted / All I wanna do is drive home to you / Baby I’m faded / All I wanna do is take you downtown.”

The headliner was Dog Blood, a collaboration between Skrillex and Boys Noize, ending the night on a high note with fast-paced electro-house beats and R&B influenced songs like “Midnight Hour.”

Despite the performances’ mystical undertones, it would be a stretch to say the festival honored the holiday’s spiritual traditions. Its representation of the Day of the Dead was fairly surface-level and came off a bit culturally appropriative given the poor representation of Latinx artists in the lineup. The event’s nods to the holiday and Mexican culture were essentially the symbols white America is most familiar with: a giant skull, a mariachi band, a stage flanked by skeletons.

What it did represent well was the spiritual culture of EDM: one full of trance-inducing songs, drug-facilitated connections, and crowds that move like one giant being. Whether or not it accurately celebrated the Day of the Dead, it was — like all music festivals — a celebration of life.