For decades, musicians have been known to experiment with LSD to stimulate their creative process. Because of the drug’s effects on the serotonergic system, people tripping on it not only experience warped sounds and images that might inspire music and lyrics but also become more open to experimenting with different styles. The result of these effects was no less than a musical revolution in the ’60s and ’70s and innovations in music that have continued up to the present day.

Many of the songs you’ve listened to have probably been inspired by acid trips, whether you realize it or not. Here are some songs that probably wouldn’t have existed as we know them without the help of lysergic acid diethylamide.

“Acid Rain” by Chance the Rapper

Hip hop may not be the genre you typically associate with LSD, but Chance the Rapper told MTV in 2013 that the drug inspired his album Acid Rap. This is perhaps most obvious on the track “Acid Rain,” where he raps, “Kicked off my shoes, tripped acid in the rain.” The song, like several on the album, is a tribute to his late friend Rodney Kyles Jr.: “My big homie died young; just turned older than him / I seen it happen, I seen it happen, I see it always / He still be screaming, I see his demons in empty hallways / I trip to make the fall shorter.” Presumably, his use of the word “trip” indicates that his psychedelic experiences helped him through the loss of his friend.

“Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots” by The Flaming Lips

Though The Flaming Lips haven’t come out and said that this nonsensical story of a karate black belt’s battle with humanity-destroying robots was inspired by LSD, there are a few clues, the first being the weirdness of the whole story. The second clue is the album cover, which features the number 25 on a wall behind the robot, as James Stafford at Diffuser has observed. We also know that lead singer Wayne Coyne is a fan of LSD; he once said that the psychedelic “SuperFreak” video with Miley Cyrus was “originally intended to be for a song that has a reference to the drug LSD.”

“White Rabbit” by Jefferson Airplane

This list would not be complete without “White Rabbit,” possibly the trippiest song known to humankind. “It became the signature for the people who were doing the things it had reference to,” the band’s bassist Jack Casady told Louder Sound. The song is based on Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, which in turn is based on — you guessed it — acid. “One pill makes you larger, and one pill makes you small… logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead,” Grace Slick sang, evoking the visual distortions of psychedelic trips.

“I Am the Walrus” by The Beatles

The only song to rival “White Rabbit” as the world’s most obviously LSD-inspired song is “I Am the Walrus.” “I am he as you are he as you are me,” the opening line philosophizes before segueing into descriptions of “egg men,” “yellow matter custard dripping from a dog’s eye,” and a “pornographic priestess.” In case that doesn’t convince you that the song was written on acid, here’s a quote from John Lennon: “The first line was written on one acid trip one weekend, the second line on another acid trip the next weekend, and it was filled in after I met Yoko.” (I would’ve included “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” but Lennon has said this name actually came from the title of a drawing by his son. Still, it’s very possible that it was written on acid, too.)

“Lysergic Bliss” by of Montreal

With their wacky lyrics and colorful, over-the-top shows, of Montreal has a reputation for embracing the weird. This song leaves no mystery regarding its meaning, with a title referencing LSD’s full laboratory name, lysergic acid diethylamide. The song, however, appears to be not just about LSD but also about falling in love (perhaps falling in love on LSD?), with lyrics like “If we were a pair of jigsaw puzzle pieces / We would connect so perfectly.” But other lines like “Wearing an olive drab but feeling somehow inside opalescent” sound more like they’re about the drug itself.

“Acid Tongue” by Jenny Lewis

“Acid Tongue,” the eponymous song off Jenny Lewis’s first self-titled album, references Lewis’s first acid trip as a young teen in the line, “I’ve been down to Dixie And dropped acid on my tongue / Tripped upon the land ’til enough was enough.” She described the trip to Rolling Stone: “It culminated in a scene not unlike something from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas—the scene where Hunter S. Thompson has to lock the lawyer in the bathroom. I sort of assumed the Hunter S. Thompson character and my friend – she had taken far too much – decided to pull a butcher knife out of the kitchen drawer and chase me around the house. … At the end of that experience, my mom was out of town on a trip of her own and she returned to find me about 5 lbs lighter and I had—I was so desperate to get back to normal I decided to drink an entire gallon of orange juice. I saw that it was in the fridge and decided that this would sort of flush the LSD out of my system, but I didn’t realize that it did exactly the opposite.”

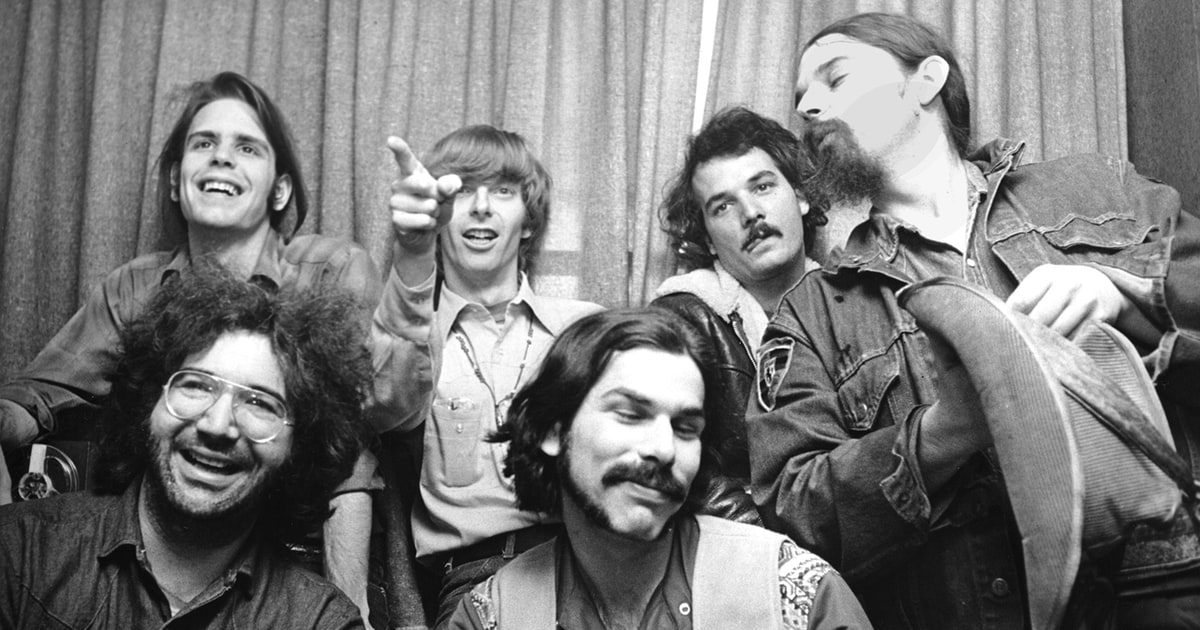

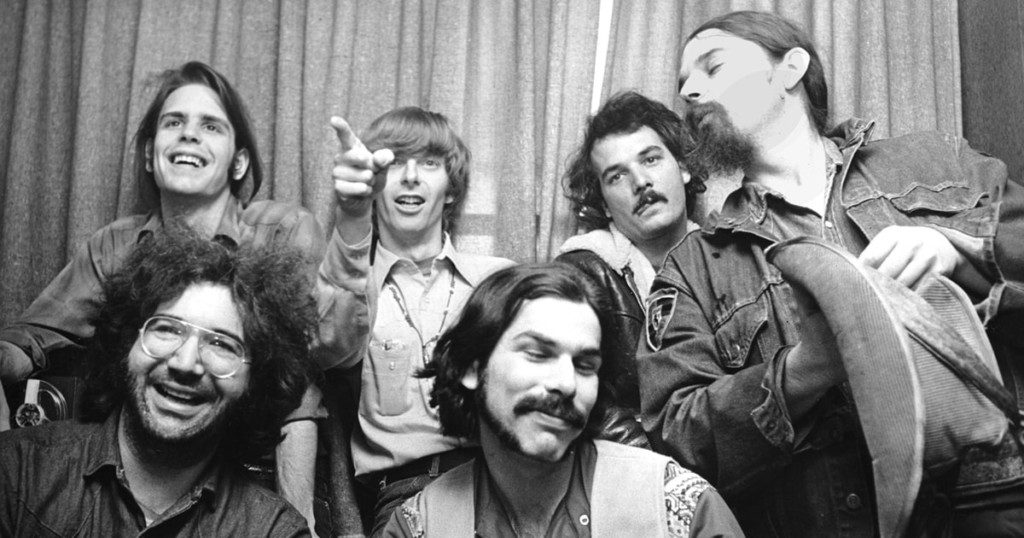

“Black Peter” by The Grateful Dead

Robert Hunter, a songwriter who frequently worked with The Grateful Dead, consumed apple juice containing about a gram of crystal LSD worth around $50,000 in 1969, after which he experienced firsthand the deaths of JFK, Lincoln, and other assassinated public figures. This scary and expensive trip paid off, though, because it inspired him to write “Black Peter,” which recounts this experience of dying in lyrics like “All of my friends come to see me last night / I was laying in my bed and dying / Annie Beauneu from Saint Angel / Say ‘the weather down here so fine.'”