Welcome to Audiofemme’s monthly record review column, Musique Boutique, written by music journo vet Gillian G. Gaar. Every fourth Monday, Musique Boutique offers a cross-section of noteworthy reissues and new releases guaranteed to perk up your ears.

The songs of ABBA are like comfort food — and that’s meant as a compliment. On the one hand, you can say it’s safe and predictable. But on the other hand, it leaves you so happy and satisfied. That’s probably partially why ABBA’s return with a new album, Voyage (Capitol) — their first in 40 years — was greeted with such rapture; after the past two years of uncertainty and stress, anything delivering a dose of feel-good familiarity is most welcome.

ABBA never officially announced they were breaking up after the release of The Visitors in 1981, but as the years passed they gave no indication had any desire to release new music. What changed that was their involvement in a high-tech live show, opening next year, where they’ll be recreated as “Abbatars.” They so enjoyed recording new songs for the show it was easy to make the decision — why not release a whole album?

Voyage (Capitol) picks up where The Visitors left off, at least in sound. But it’s an older and wiser Agnetha Fältskog and Anna-Frid Lynstad singing the songs; a bit bruised by life perhaps, but with ABBA’s trademark optimism nonetheless intact. It’s something nicely summarized by the line “I’m not the one you knew/I’m now and then combined” (“Don’t Shut Me Down”). Or consider “Keep an Eye on Dan.” If this was ’70s ABBA, the title might make you think of a boyfriend with a wandering eye. But on Voyage, it turns out to be Fältskog’s instruction to her ex-husband as she drops their son off for the weekend.

In short, don’t expect the giddy spirits of “Bang-A-Boomerang” or “Take a Chance on Me.” This is a more reflective ABBA. The lush “I Still Have Faith in You” can be viewed as a song of two people overcoming adversity, or an assessment of ABBA’s own legacy. “Bumblebee” is a quietly restrained song about climate change. The Gaelic-flavored “When You Dance With Me” takes a relationship that failed to take off as a means of contemplating the passage of time.

The music (all songs written by the “Bs” in ABBA, Benny Anderson and Björn Ulvaeus) are as toe-tappingly catchy as ever. And if some think the sentiments get mushy at times (e.g. the Christmas song “Little Things”), the album closes with the yearning “Ode to Freedom,” a prayer of hope for the future. As ever, ABBA, thank you for the music.

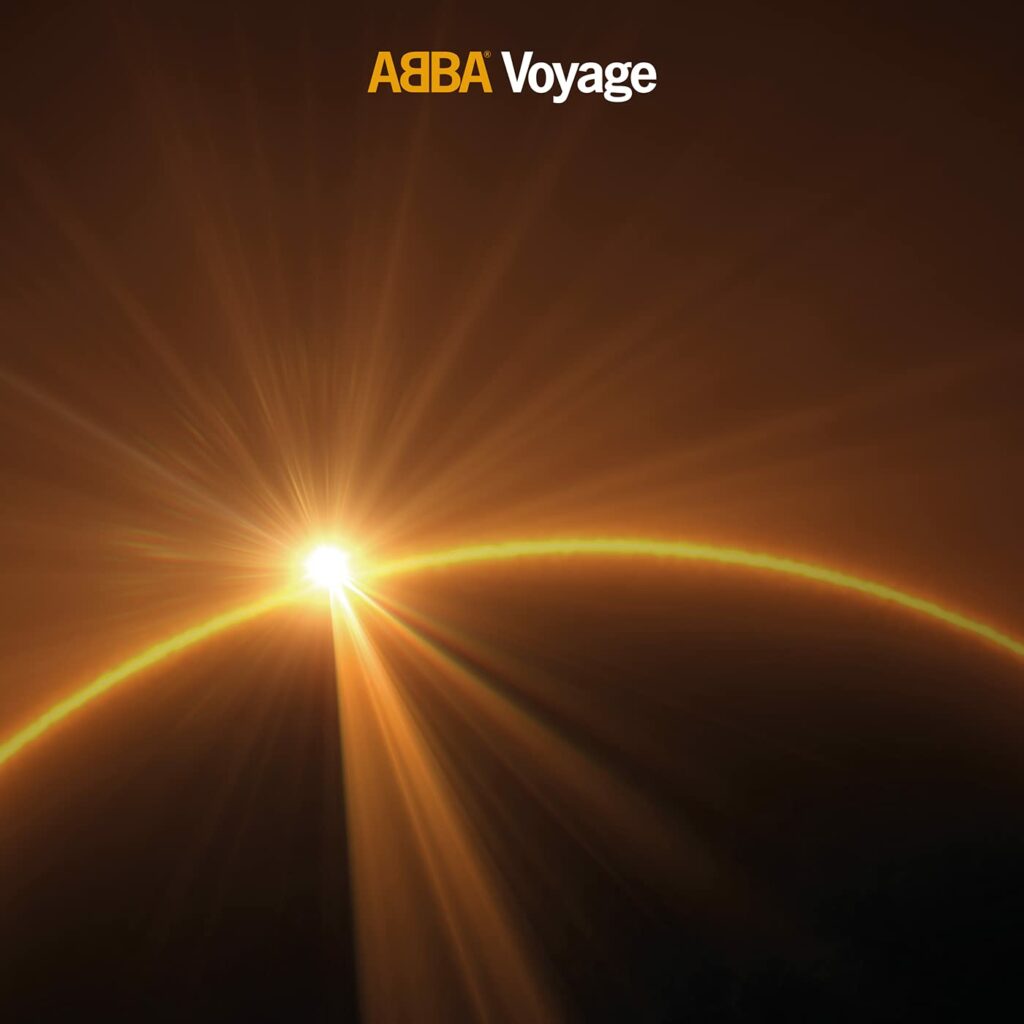

Joni Mitchell Archives Vol. 2: The Reprise Years (1968-1971) (Rhino) takes a deep dive into Mitchell’s breakthrough period as a recording artist. The first volume in the Archives series covered the years 1963-1967, before Mitchell made her first record. The new set offers a look at the work that went into creating her first four albums: Song to a Seagull, Clouds, Ladies of the Canyon, and Blue.

Though a number of tracks are outtakes from studio sessions, most of the songs are drawn from other sources: home demos, radio sessions, and live performances. She’s heard putting together the track listing for Clouds at the New York City apartment of her friend Jane Lurie; “Instead of being such a personal album, this isn’t nearly as personal an album as the last one,” she observes, as she reminds herself to add “Both Sides Now” to the album.

While there are alternate versions of songs that were later released — such as a lovely version of “Ladies of the Canyon” with cellos — it’s especially interesting to hear the songs that might have been. Like poignant ballad “Jesus,” another demo recorded at Lurie’s apartment, Mitchell accompanying herself on piano. Or “Midnight Cowboy,” a melancholy portrait of the would-be hustler Joe Buck, written but not ultimately used for the film of the same name.

Among the live recordings is a March 19, 1968 performance at the Le Hibou Coffee House in Ottawa, Ontario recorded by an unlikely tape operator — Jimi Hendrix. A big fan of Mitchell, Hendrix had arrived at the club after his own gig in the city, bearing a reel-to-reel tape deck and asking if he could record her. She agreed. As a result, 53 years later we can delight in hearing Mitchell promoting her soon-to-be-released debut album, and the poetry of “Michael from Mountains,” “The Pirate of Penance,” and “Sisotowbell Lane.” Archives Vol. 2 is a fascinating look at a songwriter in the midst of her artistic development.

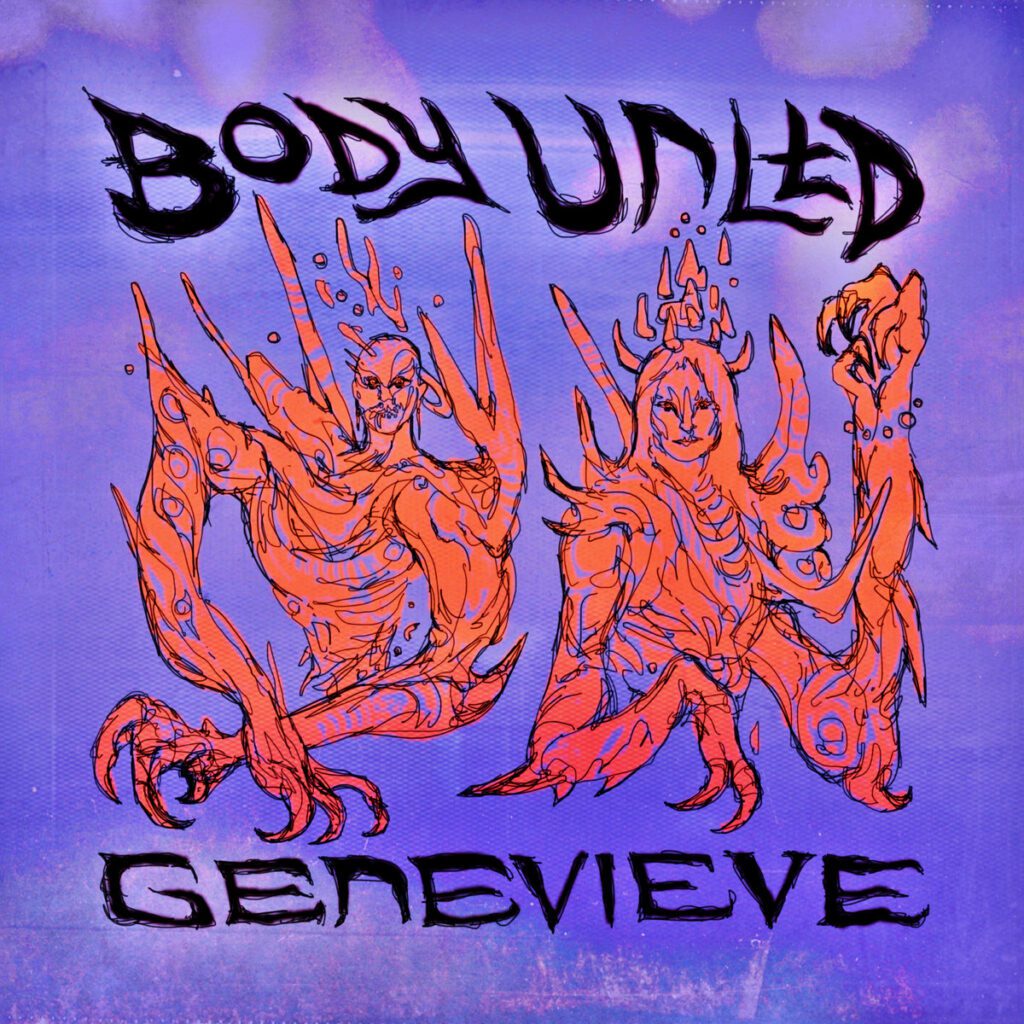

Genevieve (self-released) is the debut offering from self-described queer electro-noir twosome, Body Unltd (Irene Barber and Vox Mod). The six-track release has the clean, crisp sound of electronic devices pulsating like a metronome. But the warmth of the human voice tempers the chill, singing of desire, of the need to make a connection.

The songs evolved with Mod first creating the instrumentals, then sending them to Barber who added further music and lyrics. The words of “Coasts” touch on the isolation we’ve all felt during in recent times: “How was the long weekend?/Was it with friends, or you alone?/Is it okay I’m doing very well?” It’s not surprising that desire results from all that pent up emotion. “Where You Want to Go” is a seductive invitation to push past all your boundaries (“I give you all that I am/I got soft hands….”), but are you being taken for a trip or for a ride?

The vocals are beguiling, luring you in on “Pathways” and “Arrival.” There’s a sly humor at work too, on “Helluva Light,” an encounter with Lucifer’s daughter, who doesn’t seem that menacing; she’s just looking to have a good time. And ageless “Genevieve,” a shining star inviting you to join in the celebration and dancing until dawn.