Welcome to Audiofemme’s monthly record review column, Musique Boutique, written by music journo vet Gillian G. Gaar. Every fourth Monday, Musique Boutique offers a cross-section of noteworthy reissues and new releases guaranteed to perk up your ears.

Elizabeth King’s life was always centered around the church. “We had preachers in our family, my mom and my daddy was church people, and mom was a great singer,” she told the Memphis Commercial Appeal. “That’s just how I was brought up.” She began singing at the age of three, later recorded with the all-male Gospel Souls, and subsequently formed another singing group, the Stewart Family. But she wasn’t interested in seriously pursuing a singing career, because of her reluctance to tour while she was raising her family (she was eventually the mother of fifteen children).

Which is why it’s taken her so long — King is 77-years-old — to finally release her debut album, Living in the Last Days (Bible & Tire Recording Co.). King has a commanding voice, as is evident from the opening track, “Blessed Be the Name of the Lord,” performed acapella to further emphasize her power. Elsewhere, she’s backed by the vibrant Sacred Souls Sound Section, who make foot-tapping numbers like the title song really jump and swing. When King and the Sacred Souls lock into a groove together, as in “Reach Out and Touch” and “Testify,” the musical force they generate is irresistible. She’s just as compelling in slow burning numbers like “Walk With Me” and “You’ve Got to Move.” This is uplifting music that will soothe your soul.

When Marianne Faithfull was hospitalized with coronavirus last year, she wasn’t expected to survive. But she beat the odds and pulled through — and went right back to work on her 21st solo album, She Walks in Beauty (BMG), created in collaboration with Warren Ellis (best known for his work with Nick Cave the Bad Seeds), and featuring guest appearances by the likes of Cave and Brian Eno.

Its release fulfills Faithfull’s longtime dream of recording an album of poetry. It’s an area she’s explored before — her 1965 album Come My Way featured “Jabberwock,” a recitation of Lewis Carroll’s poem “Jabberwocky” — but never in such depth. Her resonant voice is tailormade for the classics, and when set against the languid, atmospheric musical backing, the effect is sublime. The title track is the renowned love poem by Lord Byron; “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” is John Keats’ tale of a woeful knight; “The Lady of Shalott” is Lord Alfred Tennyson’s epic ballad of a doomed young woman (Faithfull chooses the darker 1833 version of the poem). Faithfull breathes new life into these timeless works, turning them into something exquisite.

Merry Clayton has the kind of music resume that could fill the entirety of this column. You’ve heard her voice on records by Carole King, Ringo Starr, Tori Amos, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Linda Ronstadt, Coldplay, and Odetta, to name a very few, as well as her riveting guest appearance on the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter.” She’s released her own records too, and was profiled in the 2013 documentary 20 Feet From Stardom.

Now, twenty-seven years after the release of her last album, comes Beautiful Scars (Motown Gospel/Capitol CMG/Ode Records). Its appearance is even more remarkable considering the challenges Clayton has faced in the last decade; following a serious car accident in 2014, both her legs were amputated below the knee. Clayton’s resilience can be seen in her first question to the doctor: would her voice be affected? No, it would not. Beautiful Scars is the result.

Indeed, she wears those scars proudly, calling them “beautiful proof that I made it this far” in the album’s title song, so filled with emotion it moved her to tears. There’s a wonderful version of Sam Cooke’s “Touch the Hem of His Garment,” her voice soaring with ecstasy. She revisits Leon Russell’s “A Song for You,” which she first recorded in 1971, her voice now grown in stature to become fuller and richer. And as always, there are songs of the faith that helped her persevere, such as the joyful testifying of “He Made a Way” and “God Is Love.” Merry Clayton’s indominable spirit vibrates through every note of this record.

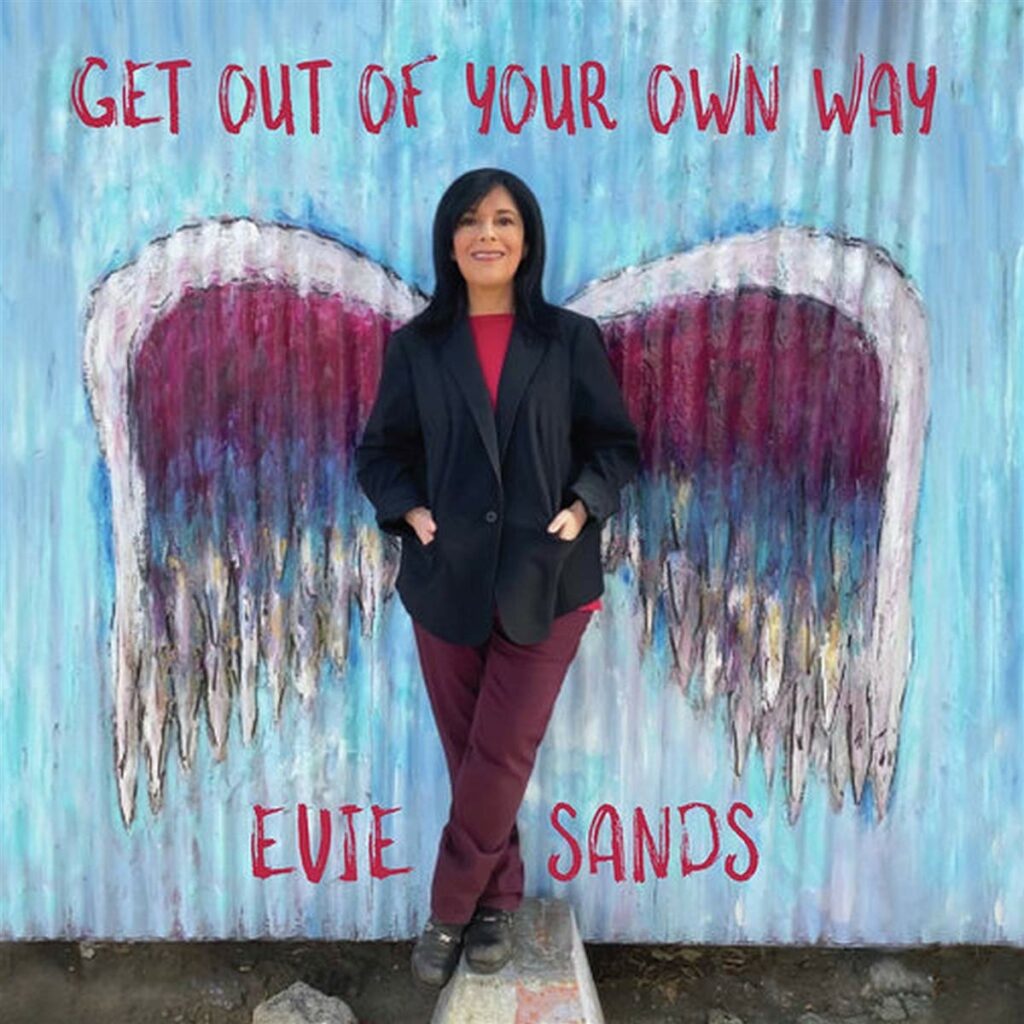

Evie Sands launched her music career in the 1960s. But after watching other artists go on to have hits with songs she’d previously recorded (including “Take Me For a Little While,” “I Can’t Let Go,” “Angel of the Morning”), she began moving into songwriting herself. She eventually stopped performing in 1979 to pursue songwriting and producing full time, though still releasing the occasional record.

Get Out of Your Own Way, on Sands’ own R-Spot Records label, is her first solo album since 1999. It’s fairly bursting with warmth and positive vibrations; the musical mood is an engaging rock/pop mix, with elements of country and soul, and rich harmonies throughout.

Highlights include the soulful “My Darkest Days,” a powerful number about overcoming despair, and the opening track, “The Truth is in Disguise,” a solid rocker addressing the confusion and uncertainty of diving into a new relationship. The title track provides a gentle reminder that you might be getting in the way of your own success. “Don’t Hold Back” is a go-out-there-and-get-’em ode of affirmation. “Leap of Faith” encourages you to make one.