[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_2″]

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_2″_last]

[/one_half_last]

Sometimes the most provocative art is that which is pieced together from various, unusual mediums and outcasted found objects, speaking as it does to obsolescence, alienation, and a crush of cultural detritus. This can apply to music as well as visual art very easily in the right hands, where signals are mixed and symbols are meshed to examine the tenuous relationships we have to the things and people that inhabit our lives.

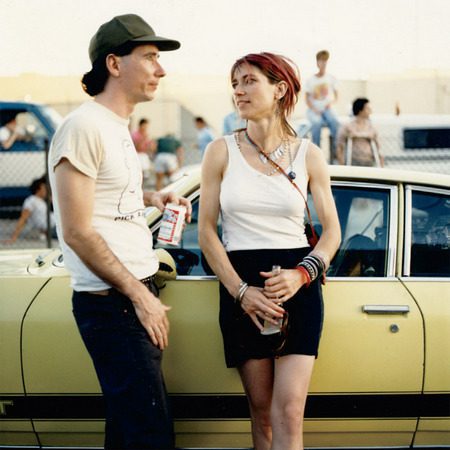

Nothing proved that better than the Mike Kelley retrospective at MoMA PS1, the largest single-artist exhibition the museum has ever curated. Collecting video works, installations, sculpture, drawings, paintings, and assemblages spanning Kelley’s entire career as a visual artist, the show opened in October and closed yesterday with a thought-provoking set from Kim Gordon and Jutta Koether.

The performance took place inside a dome centered within the courtyard, surrounded by the former school’s various galleries. An image of two tanks, one blue and one red, both swirling with bubbles, was projected behind the stage; the imagery was borrowed from Kelley’s more recent Kandor series in which he used varying representations of the Krypton city from Superman comics to explore feelings of disconnectedness. Though the hermetically sealed contents of the tanks highlighted separation, it also suggested a synergy, a transfer of materials. This conclusion might have been drawn in part to the connection that Gordon and Koether formed during the performance, as well as Gordon’s connections to Kelley himself.

Before Gordon founded Sonic Youth with Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo, she studied visual art and worked in SoHo galleries, curating shows of Kelley’s work. Kelley had been in a no-wave band called Destroy All Monsters, making the kind of music that would later inform Gordon’s. In 1985, Sonic Youth composed a live score for Kelley’s performance Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile. The bashful orange doll from 1992 Sonic Youth album Dirty is one of Kelley’s hand-knit creations, included in his photography series Ahhhhh, Youth!. When Kelley committed suicide in 2012, Gordon eulogized him in a moving piece for Artforum, providing a tender look at the decades of collaboration, mutual admiration and friendship between the two.

For the bulk of the performance, Koether and Gordon chose to reinterpret selections and ideas Kelley presented in his 1996 album Poetics. Between washes of Gordon’s guitar noise, looped sounds from a small boombox (a nod perhaps, to the visual cues that appear in several of Kelley’s works) and Koether’s nebulous synths, the two women read excerpts of a conversation that Kelley and Gordon had in Interview shortly after “Kool Thing” had been released as a single; the interview discusses at length Gordon’s transformation from librarian/art nerd into rock star/sex symbol as well as identifying racial appropriation in the the video that sounded particularly prescient in light of last year’s most criticized music videos. Gordon initially read Kelley’s questions with Koether responding as 90’s-era Gordon; halfway through the set they flipped identities again. After each of these intervals, the pair would recite a passage from Kelley’s ’93 fax-essay PSY-CHIC in unison describing a woman’s profile, crescendoing with the phrase “The sideward glance that says FUCK YOU.” At one point, Koether tossed handfuls of xeroxed copies into the audience.

In this way, Gordon used Kelley’s methods of raking the flotsam from the surrounding world, imbuing it with meaning, and repurposing it through a completely different medium. She blended text with noise much the same way that Kelley often used words in his visual works to create a contextual anchor. The cassette tapes Gordon played from her tinny boombox stood in for the stuffed animals or yearbook photos that Kelley used in various installations. The approach was mirrored brilliantly, and both uncovered awkward truths about art-making, identity, and sexuality. For Kelley, that meant exploring the perverse and the grotesque and the repressed; for Gordon that meant reconciling her responses to questions answered over twenty years ago with the woman and artist she’s become. How fitting that she was able to do so while paying tribute to a dear friend whose work grows more prolific and seductive with each passing year, whose work we have barely begun to cherish for the melange of half-truths and false memories and rejected consumerism and offbeat language that it is.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]