NYC experimental outfit P.E. get super weird on their sophomore record The Leather Lemon – and I mean that in the best way. Out March 25 on Wharf Cat Records, the album opens with “Blue Nude,” wherein singer Veronica Torres purrs, “You want to make me beg,” establishing a power dynamic right off the bat.

Musedom – or inspiration – is central to The Leather Lemon, which is brimming with mystery, romance and sex appeal. “Blue Nude” references Matisse, while “Lying with the Wolf” is based on a Kiki Smith work. But Torres (who writes the lyrics) isn’t just casually name-dropping fine artists. As she stated in a recent interview: “I’ve always been concerned with this concept of muse… women weren’t allowed to be creators, so they would just be put on a pedestal and inspire art, which I think is bullshit.”

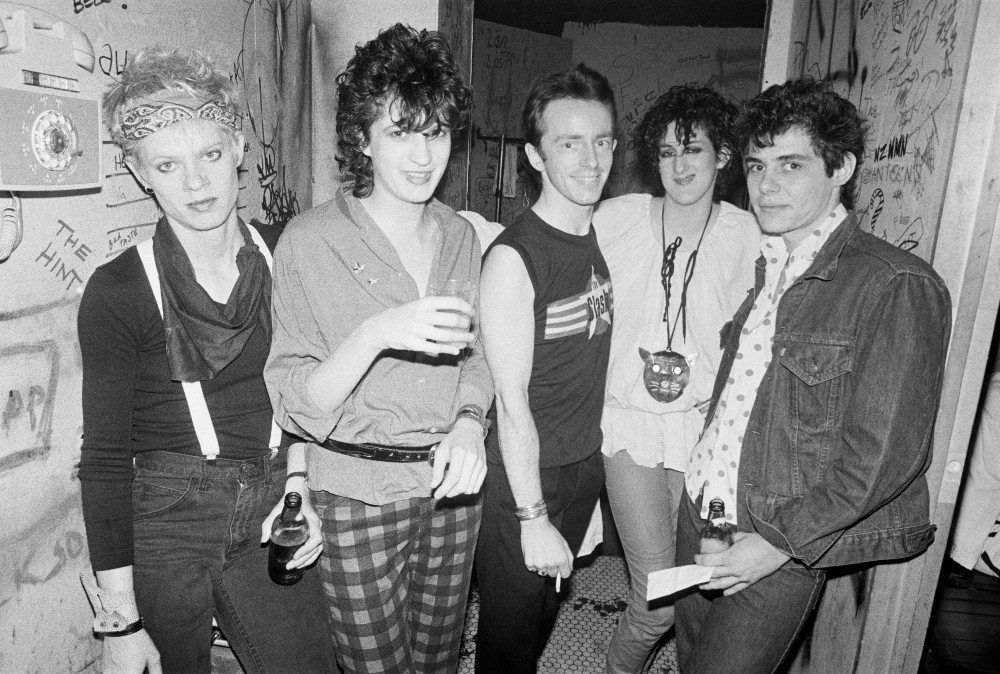

That Torres is grappling with such ideas in her lyricism becomes all the more intriguing when you consider that she is the sole woman in her band, which is a Brooklyn underground supergroup of sorts, composed of members of PILL and Eaters. Jonathan Schenke, Bob Jones, Jonny Campolo and Benjamin Jaffe (who plays the guileful saxophone slinking its way through the whole record) write the music, but as the lyricist, Torres is the megaphone imparting the band’s message. In that sense, Torres flips the script – she is not the muse; rather, she is looking outward at the muse.

When I ask her about this, she makes sure to emphasize that she is “lucky [to be] working with really talented and supportive dudes.” That said, she notes that “the whole muse concept in a historical sense [is] not very far away. You can go to the museum now and get a Guerrilla Girls tote bag – which, I totally want that tote bag – but you know, it’s funny that you’re getting this deliverable item referencing something that was only 30 years ago, which was a piece about how women weren’t in museums.”

While she is critical of this particularly feminized nuance of the muse as a concept, let us remember that its contemporary definition is “a person or personified force who is the source of inspiration for a creative artist.” While it’s a historically female word for the reasons Torres articulates, it really could be anything, and on The Leather Lemon, it is.

It helps that several members of the band are visual artists. In fact, the album title comes from multi-instrumentalist member Campolo’s visual art practice. “The Leather Lemon is actually a phrase that Jonny Campolo coined,” Torres explains. “He was making these drawings out of lemon and orange rinds. However they fell, he would sketch them, and they often looked like people.”

The juxtaposition of these unlikely materials and textures speaks to a new era for the band. Wharf Cat describes the record as “a wild ride through chewy bubblegum pop, sweeping synthetic orchestrations, and mutant club beats.” Strangely enough, what the record evoked for me was the 1988 thriller Frantic, set in the smoky back rooms of Paris nightclubs against a soundtrack laced with Grace Jones and Oscar-winning composer Ennio Morricone. My mind wanders through the enigmatic, sensual amalgamation of jazz, synthy nightclub sounds, and ’90s Bjork, the last of which Torres emphasizes as a specific influence, although she quantifies it: “Can anybody be ’90s Bjork? No. But it influenced [the record].” At one point during the recording, Campolo even described the sound as “’90s Bjorkish,” to which Torres said, “That’s what I was going for!”

I found this to be the most evident on the latter half of the record, namely tracks like “The Reason for My Love” and “Magic Hands.” The supportive nature of the band knows no gender in the sense that everyone brings their weird, unique ideas and works together to layer them. “Someone will start with something, and then it’s just building, over and over and over, and there’s a lot of editing as well,” Torres states.

“It’s nice to have people be so encouraging, enabling me to explore a different side of what I’m capable of musically,” she continues. “They’re also just so supportive of my weird lyrics.”

In that way the muse is fluid. Just as much as visual art and the idea of the muse itself are central to the album’s genesis, Torres says she drew equal inspiration from a more traditional source as well: “I’m in love, so there’s definitely love songs too.” So while she’s looking outward at the muse, she looks inward as well, and opens herself up to the possibility of being someone else’s muse.

On “New Kind of Zen,” she sings, “Make me part of your spiritual practice.” When taken in consideration with where we started – “You want to make me beg” – it sums up the idea that we contain multitudes. We can walk and chew gum at the same time. The muse is not a default position of creative resignation for women anymore; on The Leather Lemon, it’s just what you make it.

Follow P.E. on Instagram for ongoing updates.