Driving through the Catskills this past Spring, I had Sedona single “Missing in Paradise” on repeat. Sedona’s causal, hauntingly smooth vocal delivery feels instantly familiar and comforting, easily as infectious as Fleetwood Mac’s “Everywhere.” It’s an anthem to follow your gut in the relentless and unruly game of love, asking “What makes up a lover?” answering through layers of glistening synths. The bridge exists as an inner monologue of an independent woman, tired of games, on the brink of giving up, she drives back to New York City, leaving the burden of love behind while longing to feel that familiar awakening of emotional instincts. Fresh nuance exists with every stream of the song’s infectious, uplifting hooks, sweeping chord progressions, lush harmonies, and thumping bass lines. Narrative arcs and concise musical arrangement creates sonic space for healing, retrospection, and forgiveness of our own past patterns of the heart.

Sedona’s latest single “From A Mile Away” tells a tale as old as time: the breaking of trust. The pain of betrayal exists as universal truth, and healing and forgiveness must come from sitting in the emotion, and seeing it through to the other side. The song offers comfort, and a reclaiming of power, when one faces “the cold hard truth.” The intro transports the listener back in time with ’80s synth leads, and a pulsating Laurie Anderson inspired vocal pads that reoccurs throughout the track.

Both singles follow Sedona’s 2020 LP Rearview Angel; together, these releases create powerful nostalgia that feels like time traveling back to the dreamiest soundscapes of the late ’70s and early ’80s, but Sedona arrives with authenticity and a firm grip on the hybrid of modern and retro influences.

The project began as cover band of Sedona’s mother’s original music. Reclaiming an underrated and amazing catalog, Sedona began performing the songs and bringing them to life in downtown venues of New York City. It wasn’t long before she caught the attention of Terrible Records, and inked a deal to distribute original music. Now fully releasing original music, the project has evolved into an eclectic Brooklyn-based five-piece, with Merilyn Chang on keys, Claire Gilb on guitar, Margaux Bouchegnies on bass, and Tia Cestaro on drums. Sedona plays the Weird Sister Records Launch Party at Our Wicked Lady on July 14th, with Melanie Faye and Sug Daniels.

Sedona plans to one day record an album of her mother’s body of work that kicked it all off, but for now she’s breaking out by making her mark on the LA/NY indie music scene. I caught up with Sedona over the phone, during a recent vacation to Mexico, to discuss her origin story and creative process.

AF: Can you discuss a bit about your childhood and the moniker Sedona?

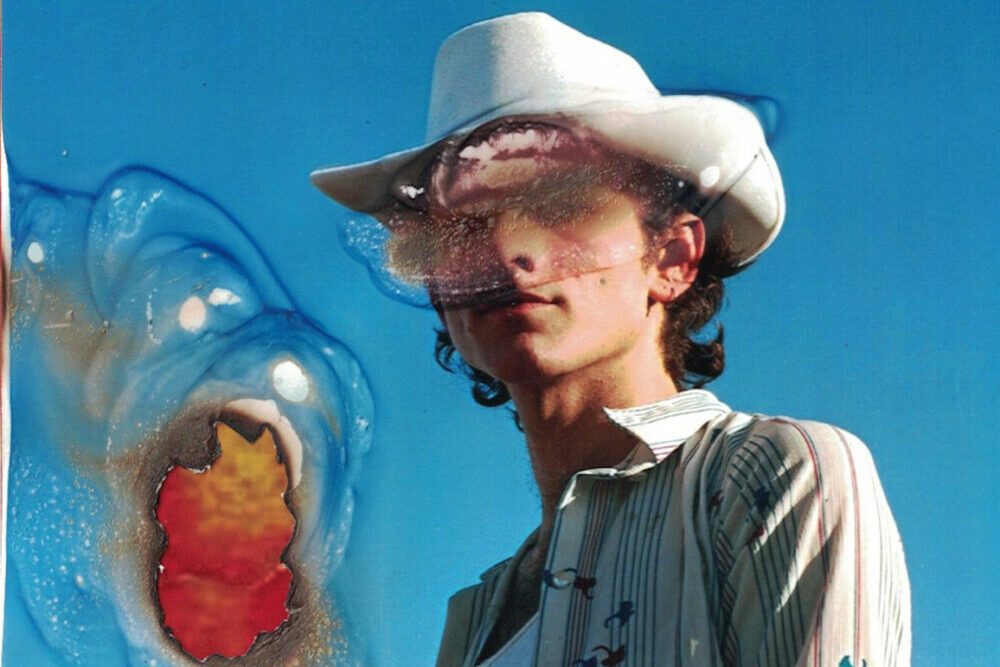

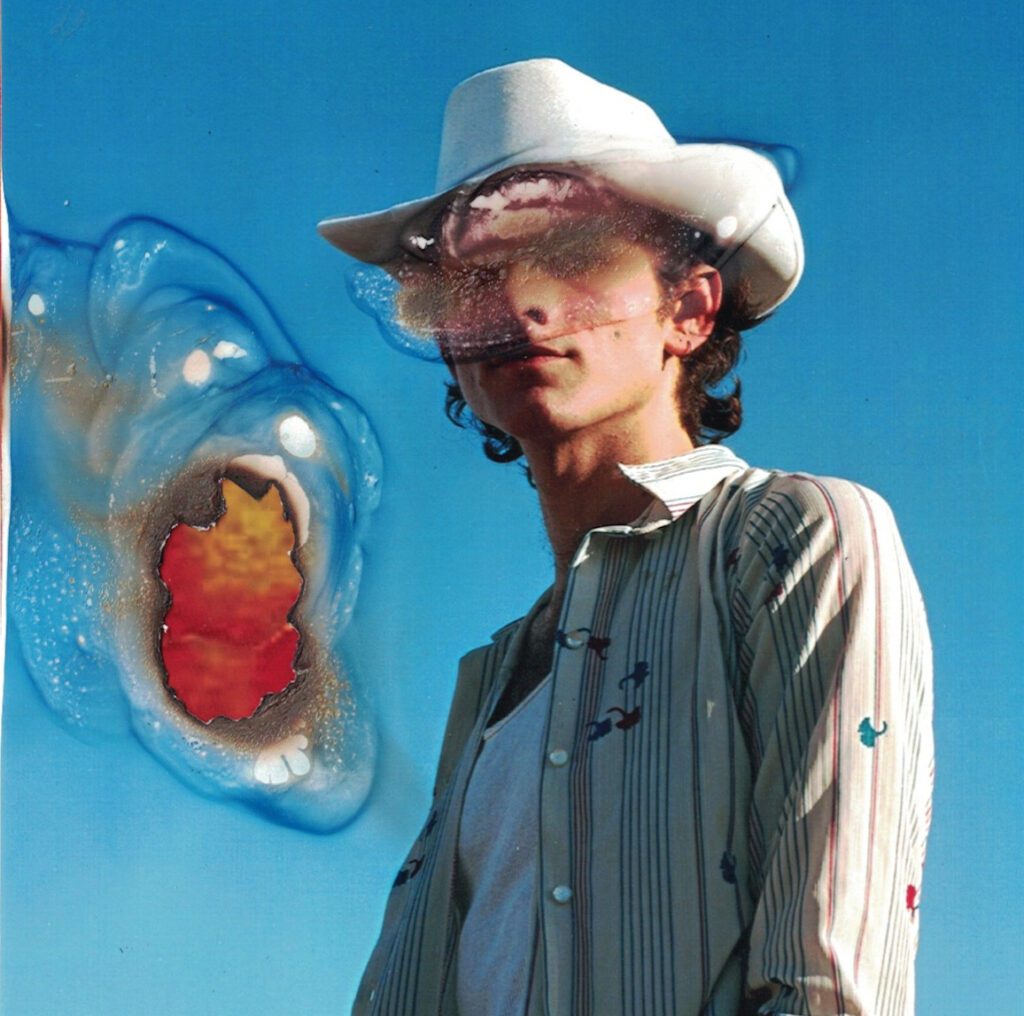

I’m from a town in the valley called Chatsworth in Los Angeles. It’s a mountain town, with a lot of horses and hiking. It’s very quaint, and has western energy. Growing up, I remember my dad would always go to this local bar called The Cowboy Palace. It’s like a saloon – a weird, hidden gem of LA. I actually wouldn’t say gem; more like a weird, hidden, forgotten underbelly of the valley.

My parents divorced when I was three or four. I was actually at their wedding. My mom and I wore matching pink dresses. Yes, I am a bastard, and although the wedding was fun from what I remember, the meaning of Sedona actually comes from their break. The first memory I have as a child is in Sedona – it was really the only memory I have of my parents being together. I remember watching a horse slip on rocks in a creek. It was the first time I ever felt a strong emotion: fear. Music helps me address emotions I’ve been holding onto. I use the writing process as a form of healing.

As for my childhood, my dad captured my entire life on his VHS camera. He’s a photographer. I was always performing and trying to bring joy to my parent’s stressful lives. I became a bit of a jester, an only child trying to make them smile. I was performing very young, writing songs, and acting out crazy stories. They’re really fun to watch, and it all makes sense to me now, why I feel so at home with singing. I grew up singing in choirs, then marching band in high school, and concert band. I used to compete in a cappella groups and travel, which was exciting.

AF: Where do you feel most creatively free to write music?

That’s an awesome question. I feel like for me, it’s not so much a place, but rather like a feeling of openness and comfort that I can really feel anywhere. I’ve written songs driving in the passenger seat of my boyfriend’s car. I’ve written songs in the passenger seat of someone else’s car. Now that I think about it, I definitely like to write in the company of close friends. I have built this little group of producers, writers, and friends, who I feel really comfortable writing with. I feel like I’ve finally found my circle. I love writing with my band. I love writing with my friends, Ben, Matt and Tony. Ben and Tony and I wrote “Missing in Paradise.”

AF: Who are your musical icons and influences?

Stevie Nicks, obviously. Gwen Stefani, Patrice Rushen. I’ve been listening to Missing Persons non-stop. Mazzy Star, Britney Spears. I love Stevie Wonder, The Mamas and the Papas, Bonnie Raitt, James Taylor, the list goes on and on. It’s really all over the place.

AF: How did you meet the amazing women that make up Sedona?

I have always wanted to collaborate with women and have a female band. I kind of set out on that journey early on. We met through mutual friends, and mostly on the internet. We actually just spent the last two weeks together, living in a house in LA recording eight hours a day for two weeks! It’s all new material that hasn’t been released for our album.

AF: I’ve had “Missing in Paradise” on repeat since it came out. I can’t get enough! What is the production process like when creating a song?

It’s different every time, and really depends on how the song started. If it’s a song with, Ben and Tony or my friend, Matt, who also produces me, we tend to write every part. They prefer it that way when they’re producing someone. I’ve tried to blend the two worlds, by sending the band the song and asking if they want to add anything. I’ll send my producers the band’s song and see what they think. It’s a lot of collaboration on all fronts. I’m kind of like the singular voice, and I co-produce everything I put out. I definitely have my hand in the arrangement and sounds. And when things come in, when they don’t, overall how things should feel. So I love that part of writing.

AF: Your most recent track “From A Mile Away” was produced by David Carrier and yourself. Can you talk about that process of creating the track?

We wrote it together over the pandemic from afar because we connected on Instagram and he was like, “I love your music” and I was like, “I love yours too!” So he sent me that track and I just popped into my home studio. I quickly sang some lyrics and top-line, and it stuck and he really dug it. So it’s literally just his track and my lyrics and top-line, and it just fits perfectly together.

AF: What was your experience releasing Rearview Angel during the pandemic?

Releasing music during the pandemic didn’t feel any different than releasing music during any other time. The only difference I felt was the sadness of not being able to perform the songs live, and give them life.

AF: What advice do you have for women in music?

All women and femme persons in music should be celebrated and their music shared with pride and joy. Women are underrepresented in the music industry, and finally women that rock are making their way to the top!

Self doubt is a bitch, but it’s not useful in the world of music making. As a woman in music, trust your gut and keep pushing forward.

Follow Sedona on Facebook for ongoing updates.