I’m in a living room overlooking the water in Vinkeveen, The Netherlands, surrounded by a dozen people tripping on ayahuasca, when the ceremony’s leader approaches my bed. “This song is for you,” she says. “I’m being guided to come to you.”

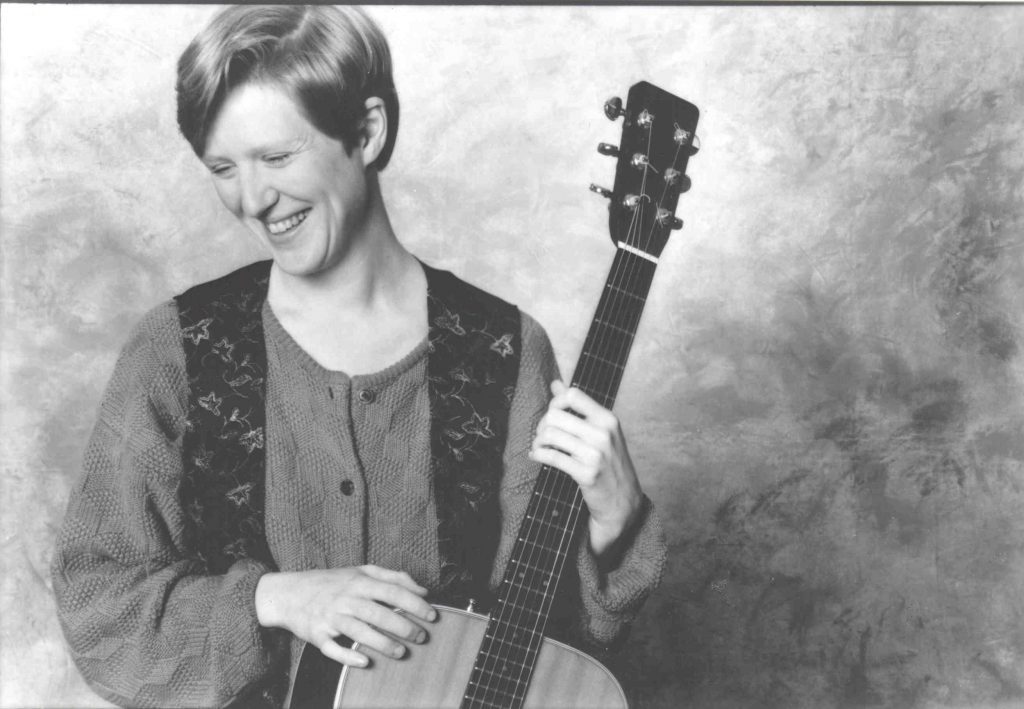

She sits down in front of me and looks into my eyes as Libby Roderick’s “How Could Anyone” plays:

How could anyone ever tell you

You were anything less than beautiful

How could anyone ever tell you

You were less than whole

How could anyone fail to notice

That your loving is a miracle

How deeply you’re connected to my soul

I’ve spent the past two ceremonies understanding the impact of my hypercritical parents’ words, and these are the exact words I need to counter them. Tears fill both our eyes as she says, “I’m crying for the same reason you are,” and we hug and cry and hug and cry.

Two months earlier, in the jungle of Yelapa, Mexico, I complain that I can’t feel the ayahuasca. “Focus on the chants,” the retreat’s leader advises. Three shamans chant strange sounds into the darkness as cartoons appear and disappear and warp and dance on the inside of my eyelids in tandem with the rhythm.

What the people in both The Netherlands and Mexico understood was that, whether through chants or pre-recorded songs, whether through tunes or lyrics, music can alter the course of a psychedelic journey.

The ancient tradition of chanting shamans exploits our brains’ affinity for repetition, says James Giordano, professor of neurology and biochemistry at Georgetown University Medical Center. “A repetitive pattern can be grounding or evocative. Grounding can bring you to a continuous sort of neurological activity.”

The “inductive chant” in ayahuasca ceremonies intends to “put you in a trance-like, meditative state” to bring on the drug’s effects, while other chants may calm down a person in the midst of a difficult trip, he adds.

Music has the power to shape trips outside these ritualistic chants, and this isn’t specific to ayahuasca. “In aboriginal societies, music-making has often been closely linked to shamanic work: the medicine-man or priest is often also the musician,” says Mendel Kaelen, an Imperial College neuroscientist who studies therapeutic uses of music. “In our research, we have shown brain processes that music and psychedelics interact on to stimulate the imagination and intensify emotionality. In our therapeutic work, music is often described as a guide or even as a transportation vehicle that carries the listener to various places.”

This is why some designate “rescue songs” to play during bad trips, says Giordano. They find this helpful for the same reason a song we love might lift our spirits after a bad day. Whether it’s a tune we like, positive lyrics, or something we associate with pleasant memories, music alters our mood.

“Very often, you hear songs, and songs will stimulate your autobiographical memories: ‘Where was I when I heard this song? What does this song mean to me?’” says Giordano. The downside of this is that music you dislike or associate with bad memories can exacerbate a drug’s unpleasant effects.

Sometimes, the same music that uplifts you in your usual state of mind can also improve a trip. “There are a range of artists who have become excellent in creating music that help people feel calm, safe, and present in their body,” says Kaelen. “Ambient music was originally invented with this purpose in mind, but other styles – for example, calm neoclassical – can provide the same means.”

But this strategy can backfire if the music pushes down the emotions rising to the surface, rather than helping you work through them. If the song isn’t meaningful to you, it can detach you from your feelings.

“A common fallacy is to think that the best solution when someone is sad or fearful is to play happy, cheerful music,” says Kaelen. “In fact, this is likely to make it worse in most cases. At most, it may help temporarily avoid [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][the pain] but not provide a long-term solution.”

“The purpose in psychedelic therapy is to not move away from oneself but to come to greater understanding and compassion for oneself,” he explains. “Emotions carry meaning, and music can be an effective aid in tuning into these emotions constructively.”

Psychedelics can take us to places where distinctions of sight vs. sound, body vs. brain, and self vs. other vanish. I’d like to believe the folk wisdom that says even plants know this, and that ayahuasca itself guided the leader toward me during “How Could Anyone” on that magical winter night.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]