In Armenian, yeraz means “dream.” It’s a fitting title for the first compilation from Los Angeles-based record label and artist management company Critique. Yeraz is a ten-track album, out digitally on February 19 and on vinyl in May, that brings together Armenian and Armenian-American artists with contributions ranging from theremin player Armen Ra to indie electronic producer Melineh. It’s a stylistically varied collection, but one that’s united in a cause. All net profits from the album will benefit Kooyrigs, an Armenian, intersectional feminist-led coalition that’s been providing humanitarian relief on the ground in Armenia and the neighboring, ethnic Armenian enclave of Artsakh during a critical time.

For 44 days last fall, Artsakh, known internationally as Nagorno-Karabakh, was under fire. In late September, Azerbaijan launched an attack, leading to an all-out war, with Armenia coming to the defense of Artsakh, which is not internationally recognized as an independent nation. In the midst of this, ethnic Armenians and allies came together in an unprecedented way, leveraging social media to bring awareness to a situation that was getting very little news coverage while also raising funds for humanitarian relief and holding protests in cities across the globe.

Karine Eurdekian, who founded Kooyrigs in 2018, had just moved from Michigan to New York when the war began and was coordinating relief efforts with the team in Armenia. In Los Angeles, Zach Asdourian, who founded Critique, was working with GL4M, an artist who had released the single “Lusavor” to benefit Armenian relief organizations. One of these was Kooyrigs, which prompted Asdourian to reach out to Eurdekian on Instagram.

Eurdekian says that she and Asdourian bonded over the “cultural consciousness” of each other’s content. They began working on collaborations, which led to Yeraz. Eurdekian describes the project as similar to swapping bracelets at a rave. “It’s just sharing our talents, sharing our creativity with one another and creating impact,” she says.

Yeraz is, in part, a means to spread awareness in communities that may not have heard about the events of last fall. “We’re trying to really expand the outreach and expanding into the music community is natural, because the underground music scene is just an accepting community,” says Eurdekian. “It’s an empathetic community, and it’s one that I’ve grown up in and Zach’s grown up in and hundreds of people in Armenia are currently growing up in.”

Meanwhile, Asdourian had heard San Francisco-based DJ and producer Lara Sarkissian drop “Lusavor” in one of her sets online. “It was honestly a dream come true to see this contemporary Armenian artist including my artist’s single in her mix, so I got in touch with her and we began talking,” he recalls.

Sarkissian came in as a creative director for Yeraz. She says that the compilation presented a “good opportunity” to connect artists in the U.S. and those in Armenia. Sarkissian has played in Armenia, where she got to know local artists like Melineh.

“It’s something very new, but something very present and the vibe is very active,” says Melineh by phone from Yerevan, the country’s capital city, of Armenia’s electronic music scene.

For the country in general, though, times have been difficult in the aftermath of the war. “The damage is huge and the traces are everywhere,” she says, adding that locals are trying to help in whatever ways they can. Artists, in particular, are doing what they can to help relief efforts, she says.

On the surface, the war may have appeared as part of a long territorial struggle between Armenia and Azerbaijan. However, standing in Azerbaijan’s corner was Turkey, who continues to deny the genocide of Armenians that took place a little more than a century ago. For those in the diaspora, the war was a reminder of historic trauma and a real fear that what’s left of Armenian’s indigenous homeland would be lost.

“I was disgusted and horrified and shocked,” says L.A.-based Armen Ra of the news from Artsakh last fall. “It’s still like a pain in my chest. It’s primal. It hurts my soul.” But, Ra adds, “out of these horrors comes so much love and attention.” He says, “I try to focus on the people who are helping.”

For Yeraz, Ra contributed his version of “Crane,” from the Armenian composer Komitas. It’s a poignant contribution; Ra opened his debut album with the same song as a means of pointing to the “core” of his musical influences. It’s also significant in light of the Armenian experience. Komitas was an ethnomusicologist who worked to preserve Armenian musical heritage and was one of the intellectuals arrested at the start of the Armenian Genocide.

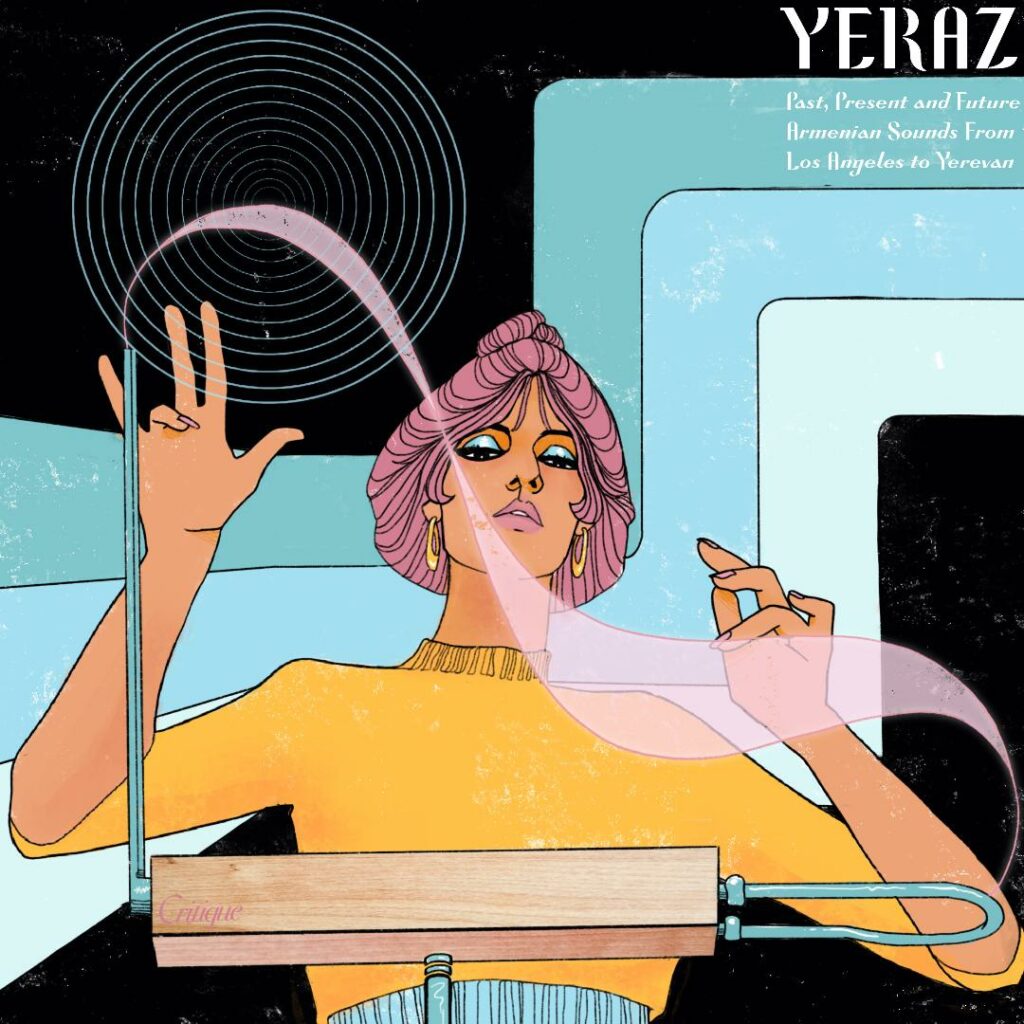

For Natalee Miller, who provided the cover art for Yeraz, helping became her focus during the war. An illustrator who has made posters for bands like Khruangbin, Miller draws inspiration from her own Armenian heritage and has an Armenian following online. “I just felt like they had given me so much, it was like an obligation,” says the artist, who is based in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. “It was now my time to give back and and the only way that I can do that is to make art.”

Asdourian surmises that the combination of the war and our reliance on online communication through the COVID-19 pandemic led to a “strong sense of solidarity and unity.” The war might not have made the nightly news in many cities, but if you’re an Armenian on Twitter or Instagram, it was probably dominating your timeline. “We were already on our phones so much that we were so much more prepared to get in touch with each other,” he says.

Plus, it unified Armenians who had been working for social justice in their own communities. “It brought together a lot of Armenians who’ve been creating an intersectional language already between Armenian movements and causes and other people’s movements,” says Sarkissian.

While the war has ended, the work to aid those impacted by it continues. Kooyrigs has several initiatives on the ground, the most recent of which, “Project Mayreeg,” helps pregnant people from Artsakh.

Beyond its goal to raise funds for Kooyrigs, Yeraz also serves to amplify the voices of Armenian artists, both in the country and diasporic communities. “I want our non-Armenian people to learn that there is so much more to our history than pain and suffering,” says Asdourian.

“Hopefully, this will catch interest for people to start supporting Armenian artists and see what they’re up to, what new sounds they’re creating,” says Sarkissian. “I think that’s also really important, to support these artists and look into other Armenian electronic artists.”

Order Yeraz now via Bandcamp.