ONLY NOISE explores music fandom with poignant personal essays that examine the ways we’re shaped by our chosen soundtrack. This week, Rebecca Bodenheimer reflects on an important friendship with a fellow fan of Southern rap legends Outkast and Goodie MOB – one that would eventually lead to her coming out as bisexual.

Touched what I never touched before

Seen what I never seen before

Woke up and seen the sun sky high, sky high.

Goodie MOB’s “Black Ice” is a lyrical wet dream for hip-hop nerds. The anchor verse of the track, by Outkast’s André 3000, is one of the most beautifully constructed flows in the genre’s history:

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your eardrums. It was a beautiful day off in the neighborhood. Yellows and greens and blues and browns and greys and hues that ooze beneath dilapidated wood.

I mean, paraphrasing Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar? That’s some deep intertextuality. The rhythmic flow of the verse alone, not to speak of its content, is absolutely mesmerizing.

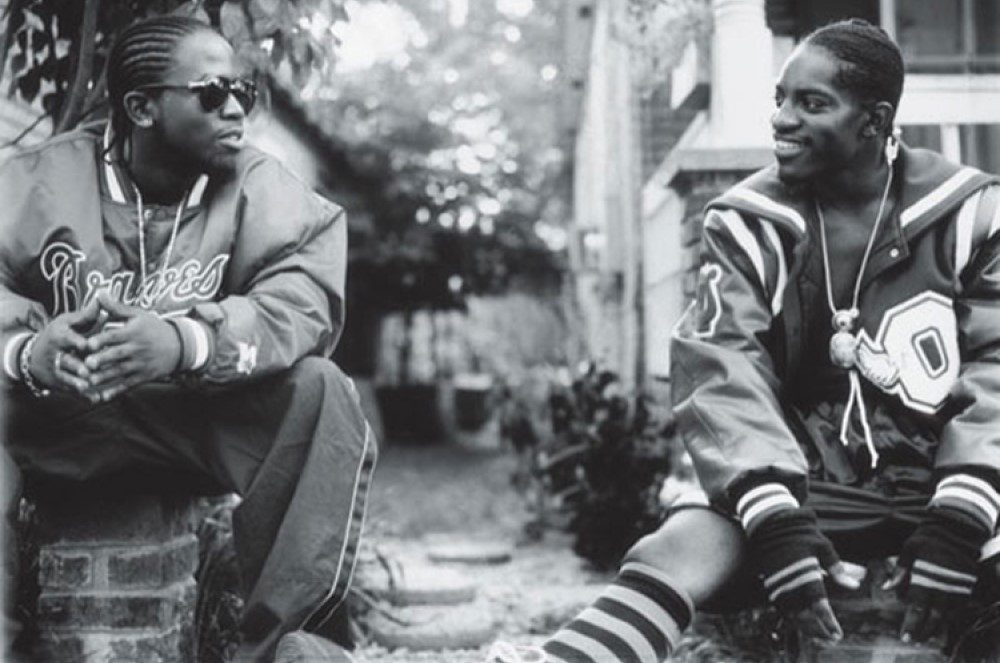

This track represents the best of many collaborations between Outkast and Goodie MOB, two groups who came out of the Atlanta-based hip-hop collective known as the Dungeon Family/Organized Noize Productions in the mid-1990s. Their 1998 albums, Aquemini and Still Standing, not only represent a pioneering moment for Southern hip-hop, but were also formative for me as a twenty-something growing into my identity.

These albums, along with Outkast and Goodie MOB’s earlier releases, were the soundtrack to a relationship that eventually led to my coming out as bisexual after I realized I was in love with my best friend. One of the cornerstones of our friendship was hip-hop: we were both white girls with a deep affinity for Black music, and our strongest bonds were forged through listening to music together. We met freshman year in the student union watching ABC soap operas like One Life to Live and General Hospital. We were smart, politically conscious, feminist young women with an inexplicable affection for a deeply patriarchal genre — go figure.

Although there is nothing inherently problematic about two white girls loving hip-hop and R&B, I now realize that some of the things we did — like my friend braiding my hair into cornrows — were culturally appropriative. However, despite our shared whiteness there were also stark differences in our backgrounds. She grew up poor in the South, calling people from the north “Yankees,” while I was a middle-class product of highly educated professionals raised as a “red diaper baby” in San Francisco. Our bond strengthened even after she transferred to a college in her hometown after sophomore year. After I finished college and moved to Italy for a year and a half — her family’s graduation present to her was a ticket to visit me there — I was back in San Francisco, and soon after, she moved out west.

It was when my friend moved to San Francisco in 1998 that I became a serious fan of Outkast and Goodie MOB; that year, Aquemini would go on to secure Atlanta’s place in the hip-hop pantheon. My friend and I would get high and listen to the groups’ various albums, breaking down the depth and eccentricity of André’s rhymes on “Black Ice,” and Cee-Lo Green’s gorgeous, soulful singing on “Liberation.” And then there were the infectious beats, which sounded nothing like east- or west-coast hip-hop; they had their own flavor. The musical interlude in the middle of “Rosa Parks” sounded like a straight-up southern hoe-down (or at least what I imagined it would sound like): there was whooping and hollering, off-beat handclaps, a country-sounding harmonica solo, and lots of southern Black slang.

I still consider Aquemini to be one of the top five (maybe even the best) albums in the history of hip-hop. It’s just shy of perfection, its one weak link the cringe-worthy “Mamacita,” which always seemed to me like it was dropped into the album from outer space. The rest of the album is a masterpiece of storytelling. Take “SpottieOttieDopaliscious.” Those infectious horn riffs riding over the laid-back beat are unforgettable; and if you had forgotten about them, Queen Bey reminded us when she sampled them on Lemonade’s “All Night.”

I particularly love Big Boi’s verse:

Yes, when I first met my SpottieOttieDopaliscious angel, I can remember that damn thing like it was yesterday. The way she moved reminded me of a brown stallion horse with skates on, you know — smooth like a hot comb on nappy-ass hair. I walked up on her and was almost paralyzed, her neck was smellin’ sweeter than a plate of yams with extra syrup.

And that last line: “Go on and marinate on that for a minute.”

I can’t imagine being from Atlanta and hearing an album like this blow up nationally; it must have been such a tremendous affirmation of Black Southern identity.

I always loved how different André and Big Boi’s styles were, and how they complemented each other: the bohemian André spitting abstract lyrics whose meaning was open to interpretation, throwing dozens of unrelated references into each of his verses vs. the down-to-earth, more relatable (yet very evocative) storytelling of Big Boi (as heard in “West Savannah” on Aquemini). And then there’s the other eccentric MC of the Dungeon Family (who later became a “problematic fave”), Cee-Lo Green. Forget Gnarls Barkley and everything that came after his crossover to the mainstream. For me, he did his best work with Goodie MOB, where he not only wrote some of the most deeply felt verses but sang almost all the choruses. I remember waxing poetic with my friend about his verse on “Cell Therapy” from Soul Food: “Every now and then, I wonder if the gate was put up to keep crime out or keep our ass in.” It still slays me with its potent truth. Cee-Lo shining a light on the security apparatus constructed around Black neighborhoods was a revelation for this middle-class white girl who had always felt the freedom to come and go as I pleased.

Among the many topics of conversation during our late-night listening sessions was the specific brand of hip-hop feminism found in Outkast and Goodie MOB songs, like “Beautiful Skin,” which extolled the importance of self-love for Black women. My older, wiser self is more skeptical of the respectability politics in this song — the idea that Black women are either queens or gold-diggers instead of complex, fully human people — but back then I was impressed by the groups’ deviation from the “bitches and ho’s” misogyny that was (and still is) so pervasive in hip-hop. On the other hand, “Guess Who,” an ode to Black mothers backed by sparse, haunting keyboard accompaniment, stands the test of time. Khujo, Cee-Lo, Big Gipp, and T-Mo each offer soul-wrenching verses chronicling the struggles of being a mother enveloped in poverty. After giving thanks for all the times his “old bird” bailed him out, Khujo injects some humor into a taboo topic: “Guess who beat the dog shit out of me kid? My momma don’t play. Shit, I had to pick the switches.” It’s not PC, but it’s a real, complex, non-romanticized portrait of Black motherhood. Although we never spoke directly about it, I wonder if my friend also thought about her own family history—her stepfather was physically abusive—when she heard this song. For me, corporal punishment was a foreign concept, but my friend’s history was proof that it wasn’t a “cultural difference” between Black and white people (as it’s often represented).

My friend and I shared a love of many 1990s hip-hop groups — WuTang, Gang Starr, Black Star — but Outkast and Goodie MOB are the ones that make me think of her. It’s because they, like her, wore their Southern-ness as a badge of honor, challenging the widespread stereotypes of the region as “redneck,” “backward,” and “racist” (as if our country’s deep entanglement with systematic racism could be contained within one region). Just like André’s infamous, defiant acceptance speech at the 1995 Source Awards when Outkast won Best New Artist and the audience booed, my friend always felt that “The South got something to say.”

Beyond casual acquaintances, I don’t think I’d ever really known anyone from the South before I met her, and she ended up teaching me my greatest lessons about class in this country and the still-existing chasms between the North and South. She taught me about what it was like to grow up white and poor, without the safety net I had taken for granted, and that in the South—despite its inescapable history of slavery and Jim Crow—there is a cultural intimacy between white and Black people (particularly those who are poor) that isn’t visible in the more segregated, supposedly more “progressive” North.

The beginning of the end of our friendship happened in the middle of a road trip from the Bay Area to the Grand Canyon in August 2002. I realized I could no longer deny my feelings for her and, unable to hide my dread or put physical distance between us, I told her. My dread stemmed not only from the realization that I was queer but that I had shame about it. It’s ironic: I grew up in one of the most queer-friendly cities in the world, and I still wasn’t immune to internalized homophobia. Although she also identified as queer by then, after a few days of thinking on it my friend told me she didn’t see us having that type of relationship. Initially I put some distance between us to heal—though I began seeking out queer community and opportunities to date women. After several months we resumed our friendship, which was forced in some ways by a holiday trip we had agreed to go on with a large group of friends; to my surprise, we became close again quickly and easily.

But in 2006, after beginning a serious romantic relationship, my friend decided our friendship was no longer healthy, that it was “codependent” (at the time she was working on fixing her self-diagnosed codependency issues and had been attending twelve-step meetings). Two months before, in the leadup to my 30th birthday, she had refused to honor my request to a group of close friends to organize a party; she said she didn’t want the responsibility of guessing what kind of celebration I wanted. I probably should have ended the friendship right then and there. Instead, I angrily vented to other friends. Then she dumped me, while we were both bridesmaids in a mutual friend’s wedding. In what to me was a stunningly selfish act, she said she just couldn’t wait until after the wedding; no matter that we would have to attend social events together and “make nice” in public, and that this might be incredibly painful for me.

The hurt, anger, and sense of betrayal — especially after I had done the emotional heavy lifting of getting over her and still trying to maintain a friendship — ran incredibly deep, more so than with any previous breakup in my life (romantic or not). The worst part was that she minimized our bond as just another friendship, completely disregarding the intense emotional attachment we had forged with each other, because she had decided it was a codependent relationship. I had been the sum total of her support system when she moved across the country to San Francisco, and I’m certain she wouldn’t have uprooted her life and taken this risk if I hadn’t lived there.

Completely coincidentally, I’ve been going through old memorabilia and letters in recent weeks and came across all the letters my friend had written to me throughout our friendship. On the inside flap of the envelope for a letter sent on March 30, 1998, she wrote, “I have this dream of a Celie/Shug type sharing/reading of all our letters together one day so I hope you’re holding on to them!” These are not the casual words of an average friend; they are a declaration of love for a best friend, of deep connection between two people that the writer expects to last a lifetime. It’s not lost on me that she thought about our relationship in terms of The Color Purple, as many of her frames of reference related to Black art and culture. But perhaps the mention of Celie and Shug also suggested she felt something more than friendship for me.

It took years to get over the betrayal I felt, but in retrospect I can see that our breakup was for the best, as she didn’t deserve the endless support I had given her. I was giving too much and not getting enough, and yet I was still clinging to the relationship.

I can’t explain why, but despite all the hurt and anger, the moments we shared — particularly our bonding over Outkast and Goodie MOB, as well as getting high and watching Friday, Half Baked, and old episodes of Wonder Woman — still make me nostalgic. That doesn’t mean I haven’t had revenge fantasies of her crawling back to beg my forgiveness and me saying no. But I can’t throw out all my experiences with her as wasted. Maybe I’m a sucker. I tend to be loyal to a fault and have always had trouble letting go of relationships I’ve invested in, even if they weren’t good for me. Whatever my psychological hang-ups though, I truly believed our friendship would last the length of our lives.

As I came to accept my bisexuality, it started to make sense as an authentic identity for me. I reflected on how I had always shied away from black and white views of the world and often found myself in grey territory. To my surprise, I ended up falling in love with a man, a relationship that began as a summer fling in Cuba, where I was conducting research for my doctorate. Perhaps less surprising was that I ended up creating a biracial, bicultural, bilingual family (another manifestation of my bi-ness, I guess).

My queerness went underground for quite some time during my 30s, not because I purposefully hid it, but because I was busy cultivating other aspects of myself: the ethnomusicologist and Cuba scholar, the mom, the PhD abandoned by academia struggling to redefine myself professionally. However, it’s still an integral part of my identity. Like most bi people, I feel like I can never stop reminding people that one’s sexuality isn’t defined by who they’re partnered with and that our bi-ness doesn’t just evaporate into thin air if we settle down with a man or a woman and are in a monogamous relationship.

Maybe in the end I’m not a sucker. Perhaps now that it’s been over a decade and my anger and pain have lessened, I can appreciate the good memories I have with my friend, the experiences that were so formative for me as a young adult, and the fact that this relationship led me to my bisexuality and turned me into a lifelong Outkast and Goodie MOB fan.

The chorus for Aquemini’s title track is an apt metaphor for this relationship, and the idea that although friendships (and romantic partnerships) don’t necessarily last forever, they can inspire a kind of ride-or-die loyalty:

Even the sun goes down, heroes eventually die

Horoscopes often lie, and sometimes “y”

Nothin’ is for sure, nothin’ is for certain, nothin’ lasts forever

But until they close the curtain, it’s him and I: Aquemini