“What a drug this little book is; to imbibe it is to find oneself presuming his process.” In her latest memoir M Train, Patti Smith speaks of W.G. Sebald’s After Nature with bibliophilic hunger. She is seeking inspiration and therefore turns to a favorite work. Smith continues:

“I read and feel the same compulsion; the desire to possess what he has written, which can only be subdued by writing something myself. It is not mere envy but a delusional quickening in the blood.”

As I read her book with a similar hunger, I realize that I’ve felt this way before, in the precise way she has described it – when I listen to the music I love. “The desire to possess” what has been written, played, and sung. This desire is so strong that it ventures upon wish fulfillment; I often feel as though I am taking communion with the music…eating it, so to speak. For a split second, I near convince myself that I have written it. That it is mine.

I often wonder if this is a personal quirk (a hallucination) or if others experience the same phenomenon. I wonder if it is perhaps the subconscious impetus to cover songs, even. What if instead of mere flattery, or tribute, possession also informed Jeff Buckley’s version of “Hallelujah” or Jimi Hendrix’s take on “All Along the Watchtower?” They certainly made both songs their own. I do not mean a jealous possession, necessarily, but an attempt to be “one with” the song, at the risk of sounding faux-metaphysical.

Cover songs as a genre get a bad rep, it seems. Covers = karaoke, or worse, Covers = Cover Bands. It was after all a throng of home-recorded cover songs that launched Justin Bieber’s career. But cover songs lead a double life. In their pop/rock identity, it is often considered a lowbrow, unoriginal form – sometimes even an attempt at latching onto the search engine optimization of the artists being covered. But in a cover song’s blues/folk/country life it goes by another name: a traditional. Throughout countless genres that could be filed under the umbrella of “folk” or “roots” music, artists recorded their own versions of songs passed down by performers before them.

Much like the poems and fables of oral history, it was common for the original authors of traditional songs to remain unknown. Take for instance the trad number “Goodnight, Irene,” which was first recorded by Lead Belly in 1933, and by many others thereafter. But the original songwriter has been obscured from music history. There are allusions to the song dating back to 1892, but no specifics on who penned the version Lead Belly recorded.

Lead Belly claimed to have learned the song from his uncles in 1908, who presumably heard it elsewhere. “Goodnight, Irene” was subsequently covered by The Weavers (1950), Frank Sinatra (1950, one month after The Weavers’ version), Ernest Tubb & Red Foley (1950 again), Jimmy Reed (1962) and Tom Waits (2006) to name but a few.

The reason so many artists (I only listed a couple) covered “Goodnight, Irene” in 1950 was because that was the way of the music biz back then. If someone had a hit record – like The Weavers, who went to #1 on the Billboard Best Seller chart – it was in the best interest of other musicians to cash in on the trend while it was hot by recording their version of the single. Not as common today of course, but in a time when session musicians were rarely credited and hits were penned by paid teams instead of performers, it made sense.

The history of traditional folk songs or “standards” is a fascinating one because it is like a musical game of telephone. The songs’ arrangement and lyrics change with the times, the performer, and the context. And that same model of change can be applied to both the artist’s motive for covering certain music, and the listener’s reaction to it.

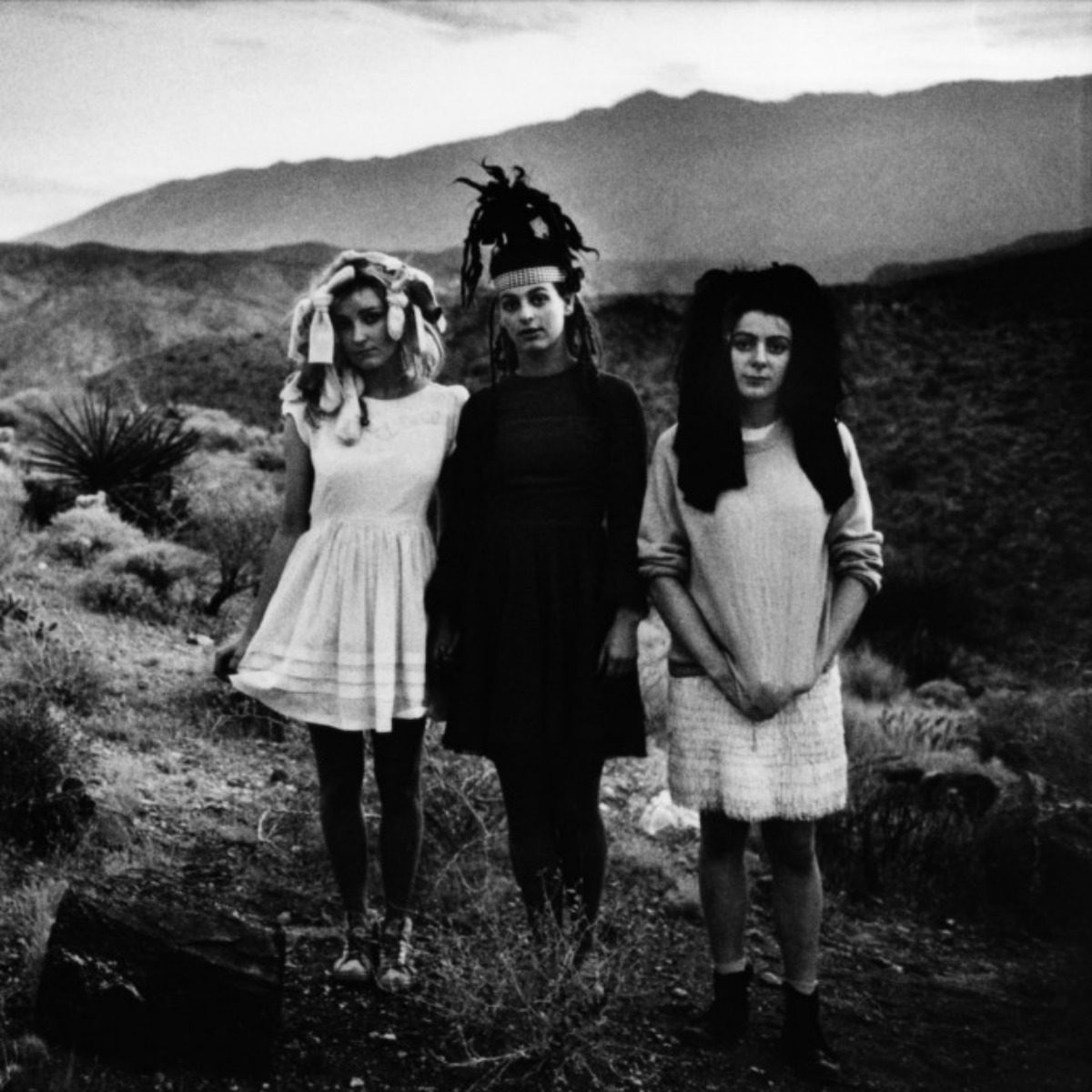

For years I quickly dismissed cover songs, finding them boring at best and unbearable at worst. But in my recent quest to become more open-minded, I have revisited many covers…and become a bit obsessed in the process. The first cover song to move me was The Slits’ version of “I Heard it Through the Grapevine,” which in itself is a pop traditional as it has been covered by everyone from Marvin Gaye, to Creedence Clearwater Revival, to The Miracles. Gaye’s version is the most widely recognized, however, making The Slits’ rendition all the more fascinating. Their 1979 stab at the Motown classic was what taught me that a cover song could be more than just a karaoke version of something. It can become a completely new medium of expression when the artist tears the original apart and stitches the pieces into a new form. The Slits did this so effectively, to the point that theirs and Gaye’s versions are incomparable.

The Stranglers achieved a similar result by reconfiguring the Dionne Warwick classic “Walk On By” in 1978, morphing the lounge-y original into a six-minute swirl of organ-infused punk. Another master of pop modification was the one-and-only Nina Simone, who somehow took the already perfect “Suzanne” by Leonard Cohen and managed to make it…perfecter. I remember a friend playing this cut for me three and a half years ago, and I haven’t gone so much as a week without putting it on since. Nina’s phrasing can make Dylan’s seem predictable, and she dances through Cohen’s poetry in a way that astonishes me to this day, no matter how many times I’ve heard it. I feel that her version is, dare I say, better than the original, though I love both dearly.

But of course, not all covers exist for the purpose of possession. Sometimes the simplest answer is the correct one: that a cover is an opportunity to pay tribute, not ironically, but with reverence. Of course, even artists performing the best reverent covers make the songs their own. Take Smog’s version of Fleetwood Mac’s “Beautiful Child,” which is such a gorgeous recording that I was heartbroken to learn it was a cover, and disappointed upon hearing the original. Ditto Bill Callahan’s more recent take on Kath Bloom’s “The Breeze/My Baby Cries.” Bloom’s take isn’t short on oddball, winsome charm, but Callahan brings a barge full of sorrow, which always wins in my book.

In similar form, Robert Wyatt somehow out-Costello’d Elvis Costello when he covered “Shipbuilding” in 1982, which reaches another dimension of despair with Wyatt’s wavering vocal performance. Another favorite is Morrissey’s interpretation of “Redondo Beach,” an oddly bouncy rendition by the King of Sad.

Though I once turned my nose up at cover songs, I seem to fanatically collect them now. I often dream up cover song commissions that will likely never come to fruition: Cat Power singing Bob Dylan’s “Most of the Time” or King Krule doing “Bette Davis Eyes” by Kim Carnes. I’d pay them to do it myself if I could damn well afford to. Until then, let the covers of others stoke your desire to possess.