CUT AND PASTE is a new column that celebrates proto-blog culture by delving into the world of self-published print media – colloquially referred to as zines – which cover a wide scope of the personal and political lives of its authors and their various cultural obsessions. The column will be a mix of zine reviews, profiles and interviews with zinesters, highlights of zine archives and libraries, and coverage of zine events in today’s still-thriving culture. For our first installment, Rebecca Kunin, who teaches a course she designed at Indiana University called “Punk, Zines, and D.I.Y. Politics,” gives us a brief rundown of zine history.

Zines are handmade and self-published print media. With relatively limited amounts of copies in circulation – both a practical constraint and ideological decision – they critique for-profit mass production. Zines often draw from the personal perspectives. As such, they tend to cover niche topics and come in many different shapes, sizes, colors, textures, and formats.

While the term was first utilized in 1930s/40s sci-fi fandoms, zines were embraced by punks in the 1970s as a counterattack to elitism in mainstream music journalism and the music industry. When punk music exploded onto local scenes, it upended mainstream notions of popular music. The core methodology of this critique was a D.I.Y. ethos. D.I.Y. suggests that one creates something – a show, song, zine, etc. – using the resources at their disposal. It suggests that an authentic message is one that is unfiltered by gatekeepers, who are swayed by corporate interests and the need to market and sell to mass audiences. A “rough around the edges” aesthetic, as it follows, is gladly embraced as evidence of human ingenuity in the face of an increasingly corporate and elitist artistic marketplace. This aesthetic (or ideal) manifested in punk music, fashion, political organizing, and print media, i.e. zines.

Zines became an important form of insider communication in punk scenes. One could turn to a local fanzine for a show review, interview, scene report, and pretty much anything else related to punk or otherwise. Beyond local contexts, zines traveled via touring bands and snail mail, spreading information and drawing connections across regional, national, and international D.I.Y. networks.

Because punks directed their rage towards corporate elitism and promulgated an ethos of inclusivity, it is easy to romanticize their outreach. While punk critiques capitalism, sexism, homophobia, and racism, for instance, it also exists within a world that is capitalist, sexist, homophobic and racist. Far from an egalitarian utopia, queer and femme punks and punks of color have had to exist within what scholar and zinester Mimi Thi Nugyen describes as “whitestraightboy hegemony.” Zines, however, became important sites for such critiques within punk spaces. Because of their participatory nature, more punk subcultures formed along these lines of critique.

One of these subcultures was queercore, a critique of homophobia within punk and conservatism within mainstream gay and lesbian movements. In the 1980s, Toronto-based multi-media collaborators Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones published J.D.s and helped to pioneer a local queercore scene. While there are many more titles than can be listed here, some of the most circulated Toronto-based zines included Bimbox and SCAB (Society for the Complete Annihilation of Breeding), Double Bill (Caroline Azar, Jena Von Brucker, G.B. Jones, Johnny Noxzema, Rex Roy), and Jane Gets a Divorce (Jena Von Brucker). Queercore, however, was not only based out of Toronto. Participants collaborated across geographic distances to other cities. Out of Southern California, Vaginal Davis published The Fertile Latoyah Jackson in the early 1980s. Up the coast in San Francisco, Homocore (by Tom Jennings and Deke Nihilson) and Outpunk (by Matt Wobensmith) were circulating widely. Out of Portland, Team Dresch bandmember Donna Dresch published Chainsaw, a homocore and riot grrrl zine. Many of the above-mentioned zines (and more) can be read in digitized formats on the Queer Zine Archive Project’s website. Although centered on zines, queercore was a multimedia punk subculture that created music, films, and social networks. Outpunk and Chainsaw, for instance, doubled as record labels. By fusing art and activism, queercore reclaimed punk’s queer roots and created networks for queer individuals.

In the early 1990s, riot grrrl grew from local scenes in Olympia, Washington and Washington D.C. into an international movement with local chapters across North America, Europe, and Asia. This activist art scene developed from feminist punks who were tired of the white boy mentality that dominated punk spaces. Riot grrrls used zines to discuss their personal experiences with sexism. Many members of this scene also performed in punk bands and advocated for feminist values and safe spaces at their shows. Famously, Kathleen Hanna of punk band Bikini Kill would call all the girls to the front at the beginning of their set. While it would be impossible to list all of the riot grrrl zines that were produced, some of the germinal ones include Jigsaw (Tobi Vail), Bikini Kill (Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna), Girl Germs (Molly Neuman, Allison Wolfe), Riot Grrrl (Molly Neuman, Allison Wolfe, Kathleen Hanna, Tobi Vail), and Gunk (Ramdasha Bikceem). These, and thousand more zines, connected femme punks across local, national, and international D.I.Y networks.

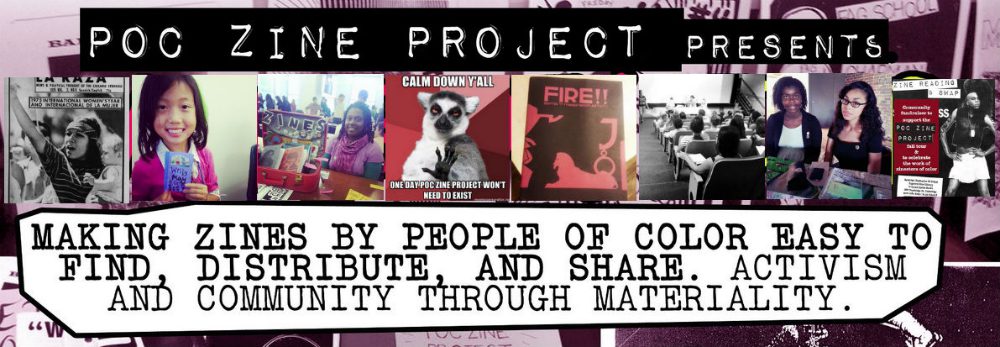

While riot grrrl opened a lot of spaces for women in punk, it is not without its critiques. Riot grrrl was mostly (although not exclusively) white, and many of its participants were middle class. Punks of color and non-white riot grrrls critiqued riot grrrl for failing to address structures of racism and their own privilege within those structures on more than a superficial level. This critique of the whitewashing of feminist punk echoed a critique of race and racism in punk across many local scenes. In the 1990s, Race Riot emerged within this discussion. Mimi Thi Nguyen and Helen Luu published Evolution of Race Riot/Race Riot 2 and How to Stage a Coup, respectively, which are compilation zines that brought together punks of color to discuss racism in punk spaces and larger societal institutions. Bianca Ortiz (Mamasita), Sabrina Margarita Alcantara-Tan (Bamboo Girl), Miriam Bastani (Maximum RocknRoll), Osa Atoe (Shotgun Seamstress), and Anna Vo (Fix My Head) are some of the central zinesters who have contributed to this discussion. Many of these zines can be read in digital formats via the People of Color Zine Project, founded by Daniela Capistrano.

By the 2000s, early social media websites and blogging platforms such as WordPress, Tumblr, Myspace, Live Journal, Bebo, and early Facebook introduced a new way for young people to interact with each other in an unfiltered format across greater geographical distances and at higher and faster rates. E-zines and blogs took zines from print to digital format.

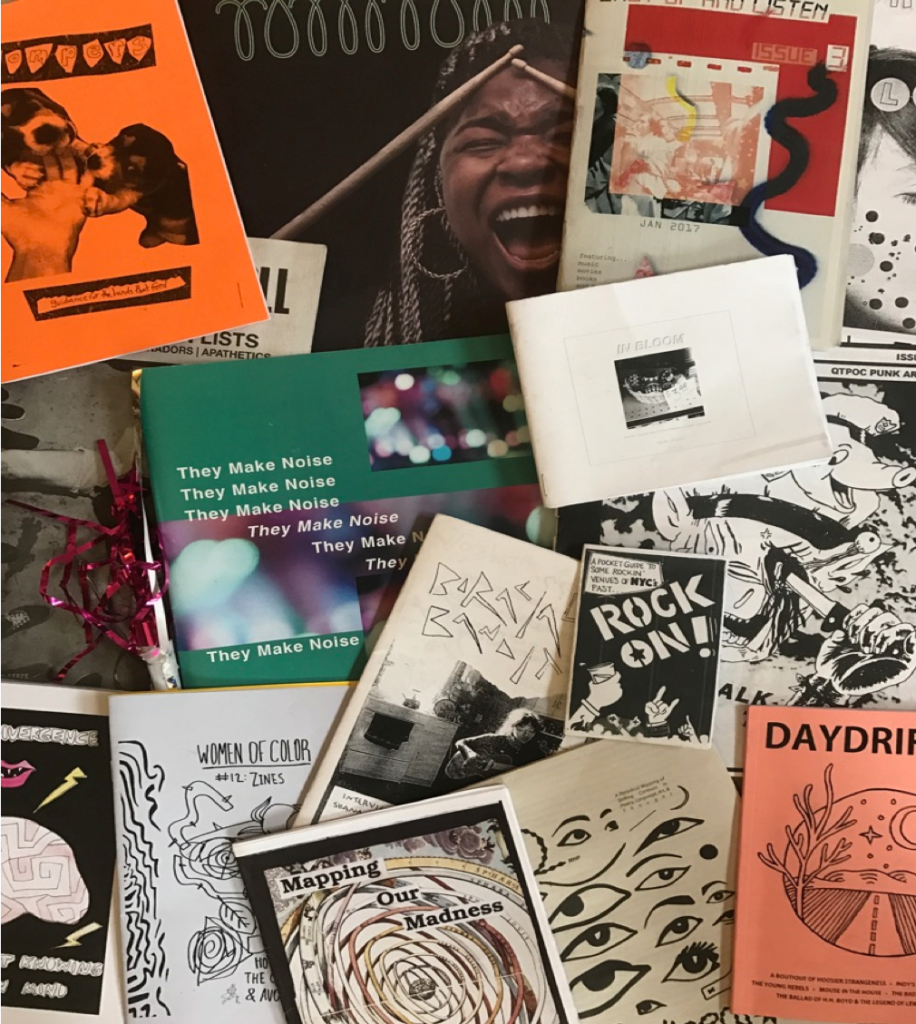

Amidst all this, zine culture in its print form has remained alive and well. Zines can be found in cities and towns across North America (and around the world) at record stores, bookstores, comic book stores, zinefests, community centers, libraries and elsewhere. A handful of stores, such as Quimby’s (NYC and Chicago) specialize in zines. Rather than a replacement for zine culture, the internet has become a tool for zinesters to access a wider audience.

Now, when I go to a zinefest, I see zines on a number of different topics. I see zines about everything ranging from music, film, animals, feminism, and racism, to food and more. It is hard to ignore that a significant proportion of zines that I’ve encountered lately relate to themes of health and wellness – a trend that I suspect might be influenced by the inaccessibility of healthcare in the US and the stigmatization of mental illness and trauma. Another widespread theme in contemporary zine publishing is prisoner rights. Ranging from political essays by scholars and activists outside of prison to poems, essays, and illustrations from people who are incarcerated, these zines critique the prison industrial complex from an intersectional lens, exploring racism, classism, sexism, ableism, and homophobia. Tenacious, for instance is a zine written by incarcerated women and compiled by activist Victoria Law.

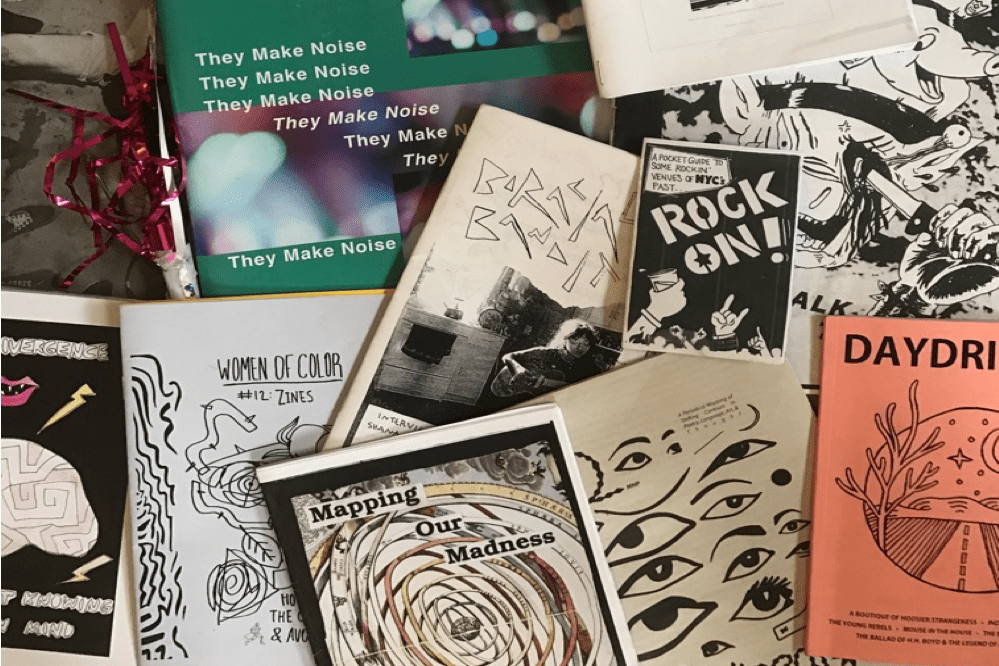

A lot of people in zine culture that I’ve chatted with mention a first zine that drew them in completely. For me, it happened when I was a 23-year-old ethnomusicology graduate student. I was at Bluestockings, a radical feminist co-op in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, and I saw a brightly colored, glossy zine that stood out and immediately drew me in. The front cover was embossed in sections with glitter tape and a metallic noise maker was attached to the binding. It was called They Make Noise by Lou Bank and it featured portraits and bios of underground queer musicians. I remember being stricken by the fact that the zine was not just words on the paper, but a carefully thought out piece of art that someone spent a lot of time and care to assemble.

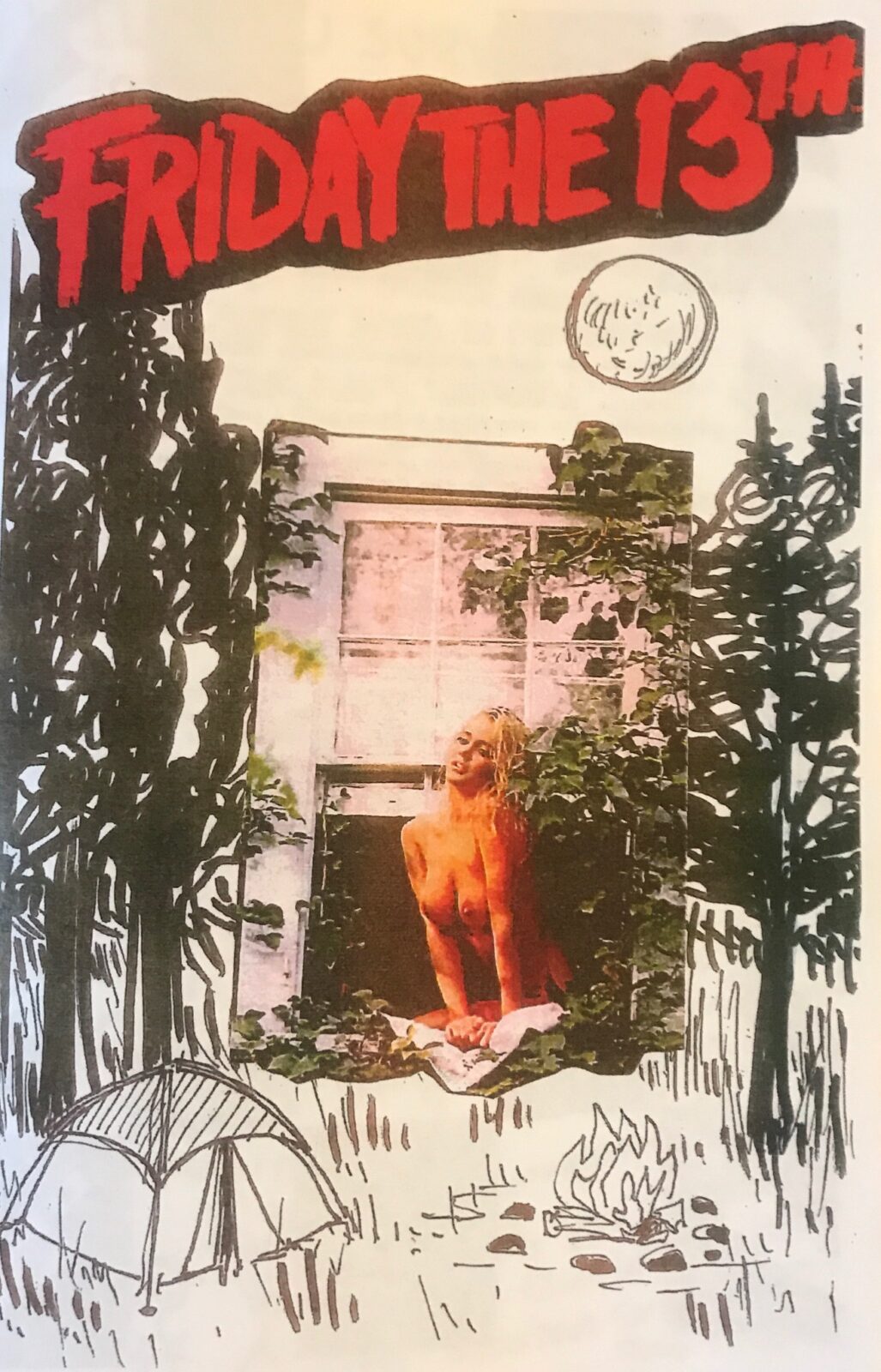

I became quickly consumed by zines and before I knew it, I was collecting them for my own bedroom archive. I made my first zine a couple of months later – my roommate Emmie Pappa Eddy and I collaborated and collectively created a fanzine about Friday the 13th. After that initial step I began to make more zines and after a couple of years, I built up my nerves to table at Bloomington’s Zine Fest. In graduate school, I have begun to work with zines in classroom settings as a creative alternative to elitist (and stodgy) academic formats. My goal with this column is an extension of this research: to introduce more people to zine culture. As zine culture is fundamentally participatory, I also humbly hope to prompt more people to grab a piece of paper and make a zine.

Recommended Further Reading

Queercore: Nault, Curran. Queercore: Queer Punk Media Subculture. Routledge: New York, 2018.

Riot Grrrl: Marcus, Sara. Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. Harper Perennial: New York, 2010.

Race Riot: Duncombe, Stephen and Tremblay, Maxwell. (editors). White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race. Verso: London, 2011.

Zines: Duncombe, Stephen. Notes From The Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Microcosm: Bloomington, 2001.