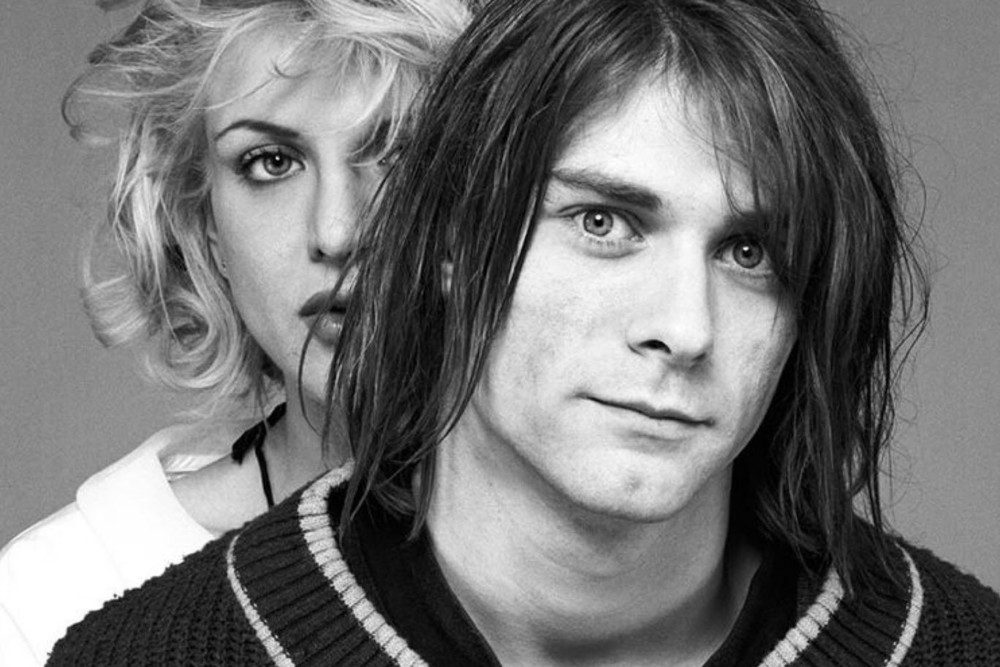

ONLY NOISE explores music fandom with poignant personal essays that examine the ways we’re shaped by our chosen soundtrack. This week, legendary ROCKRGRL editor Carla Black remembers how her sympathy for a grieving Courtney Love in the wake of Kurt Cobain’s death twenty-five years ago sparked a decade-long journey to bring gender parity to modern rock.

Like most people of a certain generation, I remember exactly where I was on April 8th, 1994, when the news broke that Kurt Cobain had ended his own life three days before. My son David had just turned six; the previous weekend, I’d slipped the organist at Pizza and Pipes an extra twenty to play a hilariously church-like version of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” on the giant pipe organ at his birthday party. It was his favorite song. As a part time bassist in an all-female ‘60s cover band, I wouldn’t dream of subjecting him to kid music as insulting to his intelligence as Barney the Dinosaur. Nirvana’s 1991 breakout hit, a paean to disaffected youth with its quiet verses, angry chorus, and video set in a flaming high school gym, had catapulted mysterious and shy Kurt into the spotlight. Fans and critics alike had already proclaimed him “the voice of his generation.” Now, I was hearing about his senseless death from an aid at my son’s school as I left the parking lot.

It was shocking, but not completely. Only a month before, Kurt had overdosed in Rome, reportedly an accident. Every station – not just MTV – covered Kurt’s suicide. He had shot himself in the greenhouse of the Seattle home that he and his wife, fellow grunge rocker Courtney Love, had only moved into a few months before with their infant daughter Frances Bean. Photos from the old-money neighborhood of Denny-Blaine splashed onto the screen. Kurt’s unkempt hair and facial scruff cut a stark contrast to the well-dressed, clean-shaven looks of the anchors that reported it. Grunge pilgrims flocked to tiny Viretta Park, the lot next to their home, etching goodbyes into the park bench with Sharpies and Swiss army knives. Courtney emerged from behind the gate and joined them in mourning.

As a newly single mother myself, I struggled to explain the death of David’s favorite rock star. I remember standing in front of the magazine rack at Barnes & Noble. It was Courtney, not Kurt, who graced the covers of most of the music magazines. Coincidentally – or maybe not – Live Through This, the major label debut album with her band Hole, was released the same week as Kurt’s death, and had already been getting significant airplay. I bought every one the magazines I found with her picture on the cover and pored through them, hoping to find an answer to explain Kurt’s passing to my young son.

Rock star deaths at age 27 were not uncommon. Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison – “the stupid club,” as Kurt’s mother had dubbed them – perished at the same age. But those deaths were overdoses. While Kurt and Courtney were both known to use hard drugs, it was still unfathomable to think how someone at the apex of their music career could take his own life. It wasn’t long before the conspiracy theories began to emerge. Maybe he wasn’t really dead after all. He could be flipping burgers somewhere with Elvis. But the most distressing of all theories, to me at least, was the suggestion that Courtney orchestrated his death. It was sexist, trite and cruel. Kurt was endlessly portrayed as a tragic angel, taken down by a demon wife. I found every bit of it disgusting.

As I learned more about Kurt’s widow, I discovered a parallel geography I shared with her. We both lived in Eugene, Oregon and the Bay Area at the same time. And in 1987 she had the lead role in a quirky indie film called Straight To Hell in which Dan Wool, a fellow student in my voice class in the mid-’80s, was the music supervisor. I remember hearing updates about the film from Dan, which notched up my remote feeling of kinship with Courtney. But while my upbringing was conventional, hers was not.

Both Courtney Love and Kurt Cobain each grew up in what used to be known as “a broken home.” After her parents’ divorce, Courtney’s mother took everyone in the family but Courtney to New Zealand to live. She spent time in reform school, was emancipated by age 16, and worked as a stripper to make ends meet. As legend has it, Kurt lived under a bridge after his parents’ split. Kurt and Courtney were two people on their own before they should have been, bonding over a voracious passion for music and a deep need to survive. By the time of Kurt’s death, the couple were a household name, and now that he was gone, Courtney bore the full brunt of Nirvana fans’ anger and disbelief.

Every evening, after David’s bedtime, I read whatever I could find about Kurt and Courtney and his mysterious death on America Online (AOL), which, in 1994, was how most of us discovered the strange new world of the Internet. It was riveting, and I found myself defending Courtney on AOL’s music message boards from what I perceived as blatant sexism. How inhumane, I thought, to anonymously lash out at someone who was suffering and so obviously in pain. He wrote her songs, they claimed. She was on drugs when she was pregnant, they said. She was a bad mom, they wrote. But I saw a vulnerable side of Courtney I found charming, intelligent, and even funny; this put me squarely in the minority. I loved the way she turned the only two existing female musical archetypes – waif folk singer and brash rocker – on their ear. She always spoke her mind, regardless of the consequences.

I was deeply offended by many – but not all – criticisms of her. Why was Kurt deified and Courtney vilified? Sure, she was outspoken, but weren’t rock stars supposed to be? The music world only embraced conventionally beautiful women as stars; men could be as ugly as Axl Rose. What about the rest of us? Didn’t we have anything important to add? It is an artist’s job to distill pain, and Courtney was the patron saint of the marginalized female, often giving away a guitar to a girl at her shows. I thought it sad how she was mocked by the press and Nirvana fans, but she seemed to be unfazed by it. I admired that greatly.

One night I logged on and was shocked to see posts from Courtney herself. The typing was challenging to decipher, but her stream-of-consciousness thoughts reflected an extremely high intelligence. She was pissed and had found a place to vent her frustrations. Initially her targets were indie musicians and record label executives I hadn’t heard of. But after finding the online world cathartic, she became a regular fixture – one of the first artists to actually participate with their fans virtually, not simply lurk.

I watched the daily drama unfold from the hulking desktop PC in my living room, and reached out to her in an email. After noticing I was one of her few adult defenders, Courtney and I became online friends. AOL charged by the hour in those days and the significant amount of time we spent messaging each other online racked up some hefty bills. Sometimes she’d call and we’d talk through the night. There was no such thing as a brief conversation with Courtney or an hour too late to call. When David went to bed, this was my entertainment: single mom by day, rock star confidante by night.

Soon I was adept at deciphering Courtney’s inimitable style. Threads I had been a part of began to appear in magazines, like Newsweek and Time. It was a heady experience to have access to such an important artist, and I took my role as “den mother of the Hole folder” seriously. With news spreading that its subject was a regular participant, the folder was the most highly trafficked on AOL.

I finally got the chance to see Hole and meet Courtney in person that fall when they performed in San Francisco. Courtney’s tour manager offered me comps and a backstage pass. “She wants to meet you,” he said. The performance was heartbreaking, emotional and sad. Throughout the set she looked up to the sky and yelled to Kurt, demanding to know why he left. Once the show was over, in the hallowed halls of Hole’s green room, the tour manager walked me over to Courtney to make the introduction. Tall and charismatic, she was covered in glitter makeup and still damp from the performance. “This is ROCKRGRL,” he said, referring to my screen name, which was more widely known than my given one. Courtney’s face lit up with instant recognition; our unlikely friendship was real after all. Following a long and awkward hug, she grabbed my arm and led me to an area far from the crowd so we could talk alone. But like a cocktail party on The Bachelor, the moment was short-lived and we were quickly interrupted by other admirers. She disappeared into the night.

That big moment may have been brief, but our enduring camaraderie created opportunities that changed the trajectory of my life. Inspired by her, but seeing a greater need, I created a magazine to build a community for female musicians that had never existed before. I named the magazine for my AOL screen name and the people I enlisted to write and do layout were my AOL friends. Journalists who also frequented AOL wrote about my plans – the first appearing in the Sunday LA Times – and many of those writers became contributors, too. I quit my typing job at a law firm to devote to the magazine full time.

I wasn’t exactly getting rich off my venture, but my little star was on the rise, becoming one of a handful of “go-to” experts on the topic of women in rock. I appeared on television, including VH1’s Behind the Music as a talking head, and a judge on a local singing talent competition alongside Sir Mix-A-Lot, Reggie Watts and Washington State Governor, Gary Locke. I booked gigs speaking to young women at colleges across the country and on panels at music conferences. I even reviewed the kick-off of Hole’s infamous Beautiful Monsters tour co-headlining with Marilyn Manson for Rolling Stone – the issue with Britney and Teletubbies on the cover. Without any financial backing, ROCKRGRL stood on its own as an influential publication, helping a generation of women find their artistic voice.

The magazine ran for 10 years and 57 issues, shutting its doors at the end of 2005. It can still be found in the libraries of many universities throughout the country. The archive was acquired by Schlesinger Library at Harvard (Radcliffe Institute) as part of their collection on American Women’s History in 2008. It still gets name-checked as an influence every once in awhile by a new female artist and that always makes my heart swell with pride.

Through the years, Courtney was a frequent contributor to ROCKRGRL. Whether it was a top ten album of the year list, kicking off a scandal about groupie abuse by all-male metal bands, or allowing me to interview her, Courtney brought positive attention to ROCKRGRL without ever overshadowing it. To me, this was what women helping each other was always supposed to look like. It was a shame Kurt’s death overshadowed her achievements.

In November of 2000, five years after the start of ROCKRGRL, I put together a conference in Seattle to discuss the state of women in music. We had panels, a trade show, and 250 female artists in all genres of music from all over the world performing throughout downtown Seattle. It took more than a year of planning, especially since I had no experience doing anything quite as daunting. I reached out to Courtney a few times to ask if she would participate but got no response. So I was surprised when, the night before the conference began, I got a phone call. “I’m coming,” she said. “What do you want me to do?”

What I had really wanted was for her to have told me this a month earlier. The staff jumped through every imaginable hoop – which included supplying her with a list of journalists in the room and creating a bag of questions she could pick through to answer. In the end, she gave a brilliant, funny and provocative Q&A to a ballroom of a few hundred female musicians, anxious to know the secrets of success, for more than two hours. Attendees got incredible advice and gossip – always a bonus – about Limp Bizkit, Stevie Nicks, Eve, Kelis and Jimmy Iovine. Courtney stayed to answer questions and sign autographs. It was sisterly, unpretentious girl talk of the highest order and an unforgettable experience for anyone lucky enough to have been there. And yes, she was completely sober for it! Her presence catapulted the conference from a cool Seattle event to an internationally recognized one (a friend vacationing in Bali said he even read about it there). But the best moment for me was her acknowledgement from the stage of my hard work, very much inspired by her.

“I had always planned to come,” she told the crowd, “But I wanted the conference to have a chance to build on its own, without it being all about a really famous person.” Then she turned to me and said the kindest thing ever, drawing tears to my eyes: “I’m really proud of what you have accomplished on your own.”

Maybe not totally on my own – I had the help of my fairy grunge mother. But twenty-five years ago, in a school parking lot, reeling from the news of rock’s biggest icon’s suicide, I never could have imagined his equally iconic widow would influence my future in such a profound way. I am forever grateful.