One of my favorite descriptions of summer, particularly its languid, melancholy months, comes from Don DeLillo’s first novel, Americana: “Summer unfolds slowly,” DeLillo writes, “a carpeted silence rolling out across expanding steel, and the days begin to rhyme, distance swelling with the bridges, heat bending the air, small breaks in the pavement, those days when nothing seems to live on the earth but butterflies, the tranquilized mantis, the spider scaling the length of the mudcaked broken rake inside the dark garage.”

This of course is not the summer of your childhood, spent racing to the river, camping out on the trampoline, and picking salmon berries in the woods. It’s a slower summer; the passage of time stifled by heat and concrete, and the knowledge that as an adult, the only distinguishing aspect of the season is its boiling sun and—if you’re lucky—an abbreviated Friday at the office. During these months I tend to favor tunes that match the heat in grime and delirium, rather than turn up to the tempo of summer jamz (who really needs to cue those up anyway, when they’re blaring from every idling car come August?). For me, summer is a season of slower music, mimicking the sluggish pace of trudging through the sweltering city, and dreaming of a place with more trees—or at least cheaper booze. For all the like-minded, hot weather sloths, here are five records to get lost in this summer.

Van Morrison, Astral Weeks, 1968

For me this record is synonymous with waking early up in a sun-filled room and shaping a slow and quiet day; making a pot of coffee, scrambling some eggs, and lazing about. Van Morrison’s 1968 freeform masterpiece blooms with verdant imagery so beautiful it is agonizing, and while I’ve probably listened to it in full more than any other record, its transportative nature always manages to take me to a place I’ve never been before. The meandering phrases of flute, saxophone, guitar, and bass make you feel like you’ve wandered an unknown region of the world without so much as stirring from your couch. Perfect for the days when it’s too hot to venture outside.

Astral Weeks feels as much a part of the sky as and stars as it does the earth. On its centerpiece “Cyprus Avenue,” spare bass roots the song into the dirt, while plinks of harpsichord and fluttering woodwind lift it skyward. It is an aching portrayal of love so painful that its narrator endures multiple bouts of complete paralysis: “And I’m conquered in a car seat/Not a thing that I can do,” Morrison sings. “Cyprus Avenue” is one of the most precise depictions of new love—something that summer can rot just as easily as ripen. The title track, which opens the eight-song cycle, is a (slightly) less heartbreaking soundscape, arranging strings, celestial flute, and brushes of guitar into a solar system of sound, at the center of which is Morrison’s voice, beaming like the sun.

Townes Van Zandt, Our Mother the Mountain, 1969

Maybe I’m so drawn to this record in the sunny months because that’s when it first came to me. Townes Van Zandt’s second album Our Mother the Mountain is filled with tales of gambling saints, witchy women, and enough booze to power a dam. Van Zandt’s lyrical mysticism made his songs sound as if they were born in an era when folklore was taken at face value—and yet his interpretation of country music was completely original. Perhaps he was so ahead of his time that he sounded ancient.

Our Mother dances between deep, undeniable melancholy, and slightly sad songs that merely sound chipper. Opening ditty “Be Here to Love Me,” falls into the latter category, in which a drunkard entreats his woman to stay. Van Zandt paints summertime depictions of a small town with his distinct twang: “The children are dancing, the gamblers are chancin’ their all/The window’s accusin’ the door of abusin’ the wall,” he drawls, depicting a bawdy saloon scene. Cowboy ballad “Like a Summer Thursday,” meanwhile, is a sombre tale of love lost, in which Van Zandt recounts the stunning traits of a long gone lady. “Her face was crystal, fair and fine,” he sings, before revealing her cold disposition. “If only she could feel my pain,” he continues. “But feeling is a burden she can’t sustain/So like a summer Thursday, I cry for rain/To come and turn the ground to green again.” It is one of the most aching summer love songs, Van Zandt blaming the heat as much as the heart for all of his grief. If anything, Townes Van Zandt might just be the best summer companion for the sweaty and miserable.

Smog, A River Ain’t Too Much to Love, 2005

Bill Callahan’s final offering under his Smog moniker turned out to be his masterpiece. A River Ain’t Too Much to Love is an hour of slow simmering folk songs brimming with naturalistic poetry. It’s hard not to associate this album with summertime, simply for the fact that its descriptions of woods and rivers and horses and valleys are so colorful and numerous. “Drinking at the Dam” recalls a particular kind of smalltown summer, where adults are absent and the brambles are the place to hang out and flip through “skin backs.” The sun is as much a part of this record as broken hearts and booze are to Our Mother the Mountain, and its rays fall upon rivers, bedrooms, and forests of pine, adding a waking melancholy to Callahan’s pensive lyrics. It is a record so stifled by heat, all there is to do within it is lie around and think. “It’s summer now, and it’s hot/And the sweat pours out,” Callahan sings on “Running the Loping.” “And the air is the same as my body/And I breathe my body inside out.” A River is replete with this kind of imagery, and that’s exactly what makes it a pleasant companion for the sweltering season.

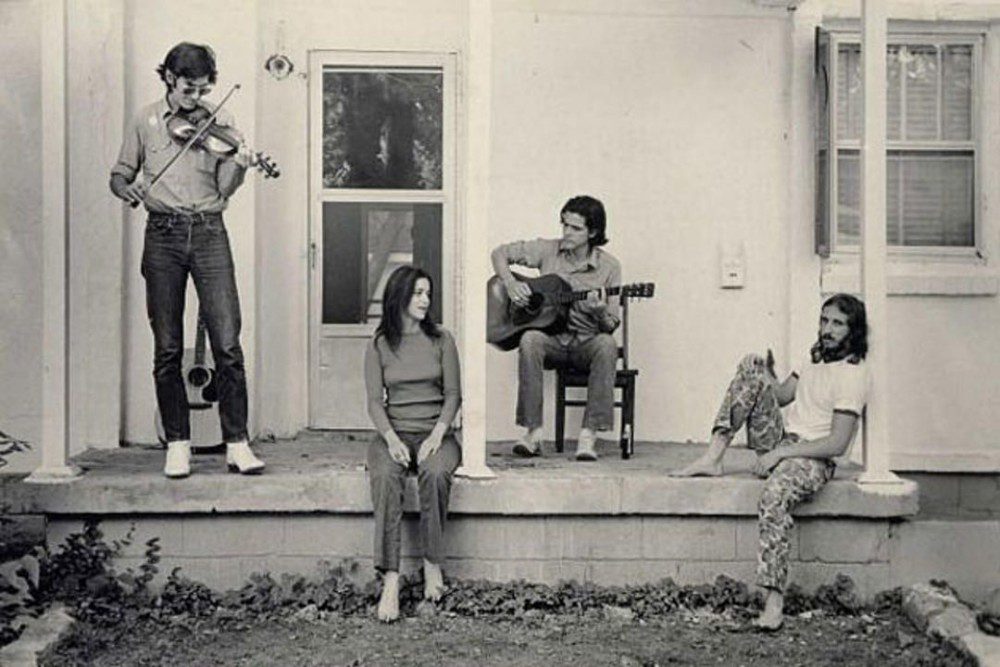

Bob Dylan, Nashville Skyline, 1969

Along with Astral Weeks, I’ve listened to Dylan’s country delight Nashville Skyline so many times in my life, it automatically qualifies as a “Desert Island Disc,” god forbid I ever have to pack that suitcase. Aside from its beatific album cover, featuring Dylan tilting is hat like a southern gentleman against a blushing sunset, Nashville Skyline is bursting with the stuff of rural summer: Bluegrass fingerpicking, lazy lovers, and backwoods euphemisms involving every type of pie you can name. Opener “Girl From the North Country” (a duet with Johnny Cash that reimagines the original version from 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan) features the lone mention of cold weather and winter coats before the record bursts into the jubilant guitar duel, “Nashville Skyline Rag.” This album is a lively companion for cooking summer meals and drinking beer on the front porch. Heck, it’s so homey and warm, it can even make you feel like you have a porch.

Amen Dunes, Freedom, 2018

Damon McMahon’s fifth studio album as Amen Dunes may have been released in the dead of winter, but the 11-song suite is radiant and lush—far more suited to aimless summer strolls than March hibernation. The entirety of Freedom is rendered with production details that place you seaside, on a boardwalk in shirt-wilting temperatures. The bright riffs of guitar, the breezy reverb, and McMahon’s languid delivery all move with the pace of light waves bending on hot air. While the previous albums I’ve mentioned might lend themselves best to lounging around light-filled rooms or dank taverns, Freedom begs you to walk around town and project its sun-faded imagery before you. Whether it’s the nostalgic twang of “Skipping School” or the beachy bent of “Miki Dora,” this is a record that can weave silvery summer blues into tapestries of hope.