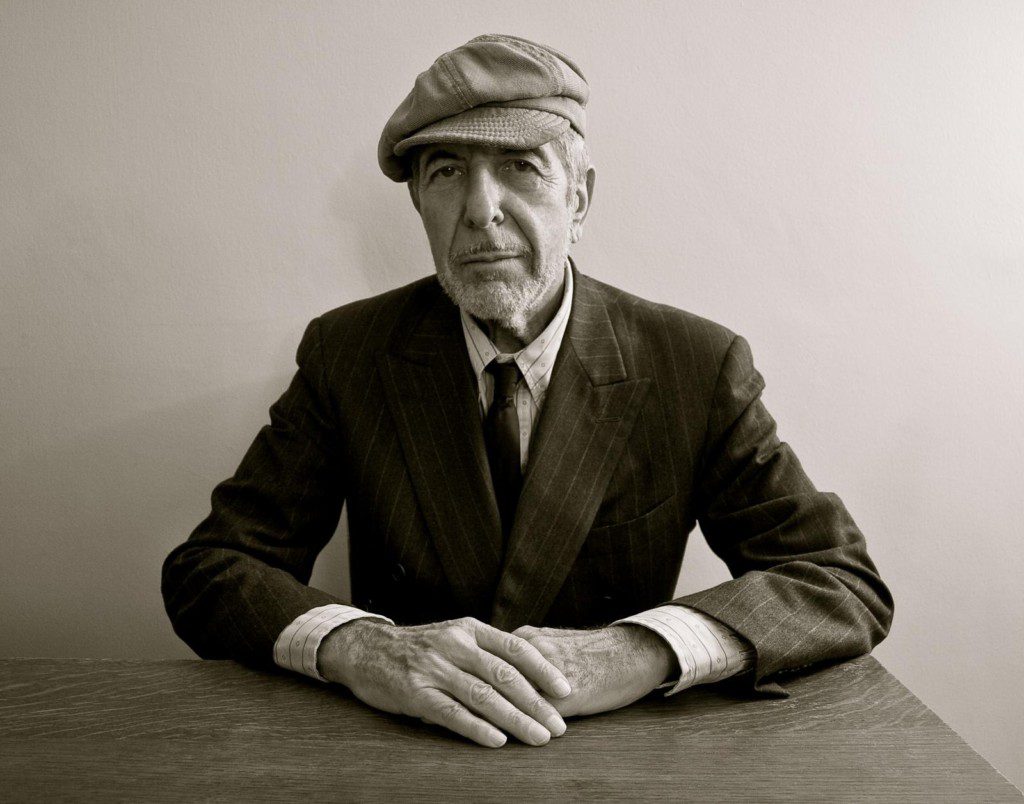

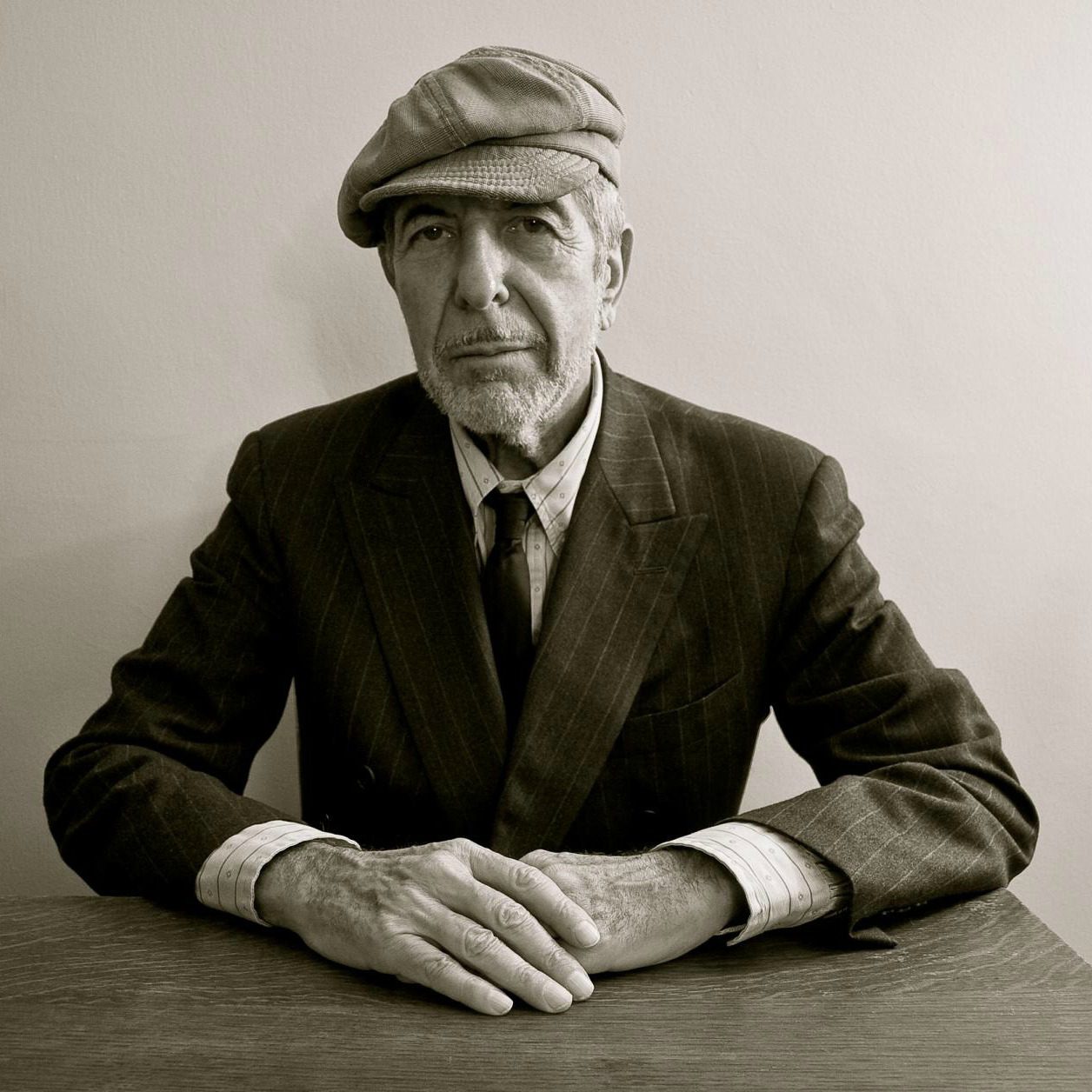

No one really wants to be a curmudgeon all of the time – not even me. If Only Noise leans more towards the darkness one week, I strive to be more upbeat in subject matter the following week. But in addition to the numerous tragedies that befell us last week, including the election, the death of Leon Russell and the election, we also lost one of the greatest poets of all time, Leonard Cohen. His name has now been added to a long list of the year’s casualties. The enormity of the musicians 2016 has robbed us of – David Bowie, Prince, Alan Vega – is seemingly colossal, as if the stars were perfectly aligned for the fall of giants. I fearfully wonder who will make it through the year, and dare not speak a word for fear of cursing anyone.

When David Bowie passed in January, I was distraught with the rest of the world. Having just pitched an article to The Guardian the night before his death investigating what Blackstar could teach contemporary musicians about longevity, I felt cosmically complicit in his death after the fact. Imagine the spook I felt waking to “RIP David Bowie” tweets the following morning. That night I sat at my desk, staring straight ahead at the wall, until my phone buzzed, and I boarded a cab to Sunset Park. I entered a sweet-smelling, steamy apartment that felt like it was in another city – in a house perhaps, with books and scraps of paper everywhere. The man who lived there offered me seltzer water and Oreos. A framed Leonard Cohen poster hung to the right of his bed.

I could barely express the overwhelming sadness I felt from the loss of Bowie that night. My companion was less distressed, but had witnessed such mourning all day long as his work was a scant block from Bowie’s SoHo home. “It is sad of course, but honestly, I’ll be more upset when Leonard Cohen goes,” he said gravely.

Ten months after we lost The Thin White Duke, I found myself slowly ascending the escalator of a theater in Times Square, meeting the very man with the Sunset Park apartment for post-election, action movie distraction. Tweets suddenly flooded my phone: “RIP Leonard Cohen,” “Now Leonard Cohen! Fuck this year!” and the like. I was already wobbly from the political climate, but I nearly fell off the goddamn escalator at the sight of such news.

It is only now I am learning that Cohen himself suffered a fall the night he passed, which directly contributed to his death. As the press release from his manager said, Cohen’s death was, “sudden, unexpected and peaceful,” which contradicts the songwriter’s claim in an October interview with The New Yorker that he was “ready to die.”

When Cohen’s parting masterpiece You Want it Darker came out last month, I thought of another pitch idea – one that never made it into an email but that I’d mentioned to friends and family. It went something like: “Is You Want it Darker Leonard Cohen’s Blackstar,” insinuating that the aged poet, like Bowie, knew his fate before we did, and was saying goodbye in the best way he could. Given this pattern, I am now convinced that I am slowly killing my favorite musicians by way of my unsuccessful pitches, which is depressing on numerous levels.

We have lost a songwriter, yes – a poet, of course. But we have also lost an invaluable translator of human emotion, in all its unperceivable complexities. When I came to his music in high school, his abstract yet exacting lyrics left me stupefied. I believe that his words truly altered my approach to writing, and while I am not and never will be anywhere near the caliber of a writer he was, I know I am all the better for being exposed to him.

And isn’t that the point of pop music? Of any kind of music, or art? To better know ourselves, in ways we couldn’t imagine were possible. Cohen’s art, his words particularly, cut so sharply to the core of human experience that you can’t really feel the incision until after his knife is removed. It is a clean cut – the effect of a specter whose impression lasts far longer than its presence in the room. He was a subtle legend. A quiet titan.

As with most musicians who have altered my perception of what makes great art, there is typically one or a few people that I directly associate with the artist. With Leonard Cohen, it is no different. One friend who is much older than I am bears an eerie resemblance to a young Cohen. He was the person who played me his music, despite the fact that a copy of Songs of Leonard Cohen had been nestled in my dad’s record collection my entire life. So when I heard “One of Us Cannot Be Wrong” for the first time, and it effectively floored my soul, that album was waiting for me right at home.

I called my old friend as soon as I could upon hearing of Cohen’s death, and asked him what the poet had meant to him. This friend, who often speaks in florid non-sequiturs, said that to him Cohen seemed like “the standard for effortless grace…you can listen to him over and over and it just keeps opening up. He really is a sort of sacred ground that’s vast, elusive, and hard to talk about.”

It is perhaps even harder to speak of for my friend, who was sired into the lugubrious cult of Cohen by his mother in the ‘70s. Not long after, his mother died when he was only 12, and I sometimes wonder if Leonard Cohen is a signifier for her in the same way that Bowie is for my mother. Memory cuts deep and clean just like a perfect song.

Leonard Cohen, though enormously different than David Bowie, was similar in the sense that he never tarnished. In his decades of writing and recording, he remained at his own golden standard, one that few others have touched. Despite his grave, death-welcoming remark to The New Yorker last month, he adjusted his statement in a later press conference, smirking and clutching a cane with his right hand:

“I said I was ‘ready to die’ recently, and I think I was exaggerating. One is given to self-dramatization from time to time. I intend to live forever.”

Regardless of Cohen’s dry humor as he spoke those words, and the uproarious laughter that met them, there is a peaceful truth within them. Yes, it is eerie that Cohen died not long after redacting his pact with death, but I think he knew exactly what he was saying. And who’s to say that he hasn’t lived forever already?

Perhaps true immortality lies in the ability to look death in the face and acquiesce to its beckoning, imparting one last gift to the world as you leave it.