It was 79 degrees outside when local DJ Steve Dahl set fire to a crate of disco records in a publicity stunt so hot, it scorched music history. Disco Demolition Night happened in Chicago on July 12, 1979. But in many ways, the event doesn’t feel too distant.

Blowing up records was supposed to boost ticket sales for White Sox games. Higher-ups at Comiskey Park were looking for ideas to get butts in seats, and rock-radio personality Dahl pitched this: If patrons sacrificed a disco album at the door, they could get in for 98 cents (about $3.50 in today’s money). On a good night, the ball park could attract 15,000 to 20,000 people. That evening, Dahl attracted almost 50,000 individuals — all eager to see a genre created by and for women, queer people, and people of color go up in flames.

Even now, talking to progressive people of that generation, I’ll hear that disco was music of the elites. I have to understand, they insist, that disco was about an urbane cosmopolitanism, and that’s really what Disco Demolition Night was rebelling against. Disco was driven by electronic sounds, not “real” instruments, and it’s vapid plasticity was embodied by Studio 54: beautiful celebrities, expensive clothing, and a bacchanalian excess that was alienating to “ordinary” people.

Never mind that Chic’s “Le Freak” — which ranked number three on Billboard’s top singles of 1979 — is an ironic celebration of the nightclub; its refrain comes from being told to “fuck off” (which became “freak off,” then “freak out”) by Studio 54’s doorman. Sometimes even the “elites” didn’t fit into their own scene, and that element of exclusivity was part of the charm. In that sense, “Le Freak” proves the ultimate expression of disco as a space where anger and joy coexist, especially for those at the margins. That sentiment is rooted in the genre’s anti-fascist beginnings.

As Peter Shapiro describes in his book Turn the Beat Around, the music can be traced back to a small French club called La Discothéque that operated during German occupation. Even though Hitler considered it beneath “good” citizens, he did little to slow France’s famous nightlife, believing it would keep Parisians too distracted to resist German control. While popular clubs like the Moulin Rouge adapted to cater to Nazi officers, holes-in-the-wall such as La Discothéque used cultural contraband like jazz music to identify themselves as safe spaces for plotting against the Third Reich.

Under Nazi rule, large public assemblies and dancing were forbidden. This made underground clubs (which were often, literally, in basements) necessary sites for political organizing — but also for laughter and fun. When WWII ended, La Discothéque and similar spots endured because they continued presenting an escape from the repressive forces of daily life. Europe was taking strict austerity measures, and radio broadcasts were treated as public services that disseminated news and cultural ideals of music. To hit a place like La Discothéque meant experiencing moments of revelry and soundtracks not prescribed by the state.

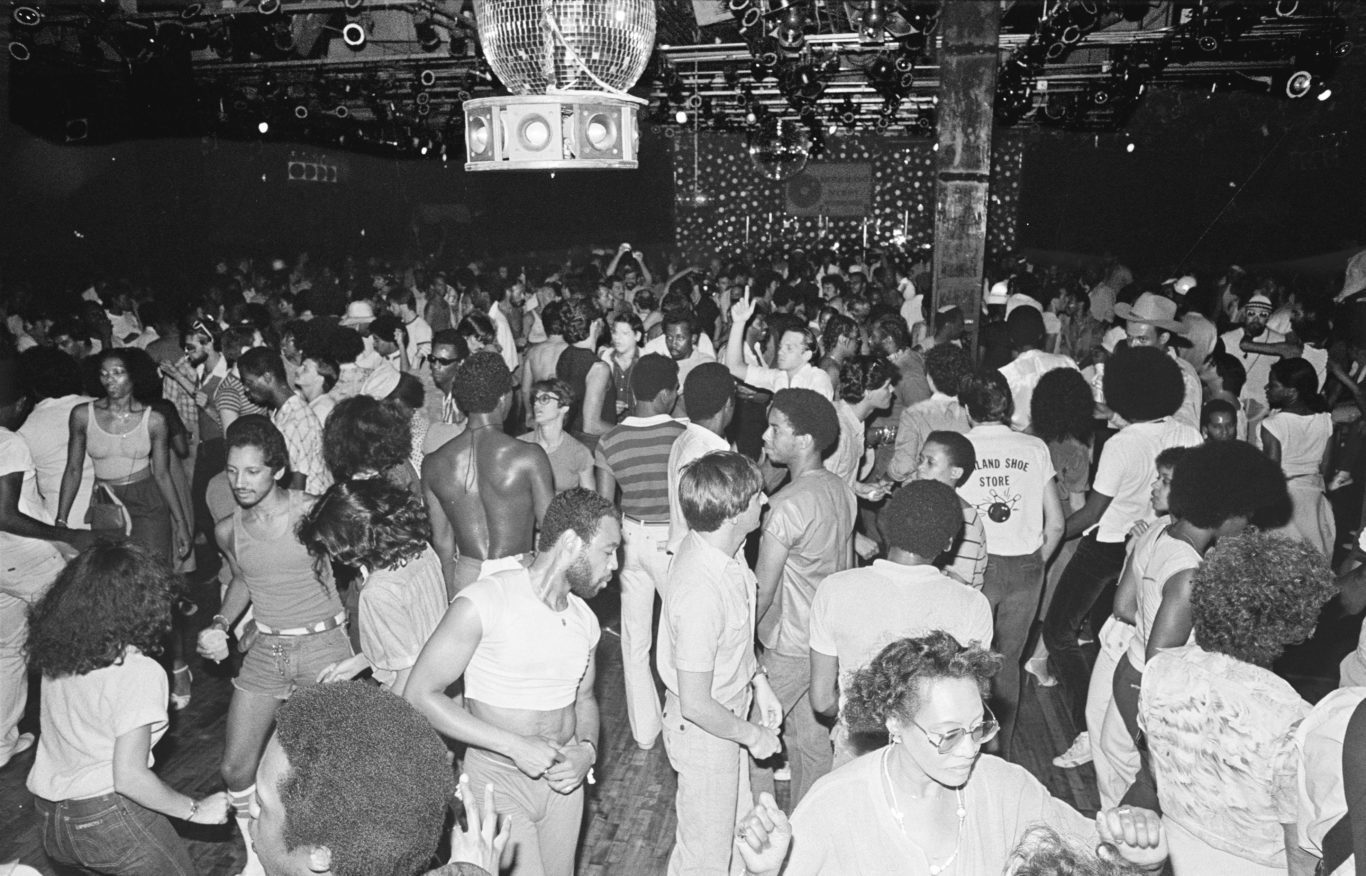

In the post-war years, La Discothéque’s club model — screening clientele, foregoing live bands for curated selections of recorded music, and offering something out of the ordinary, even bordering on decadent — trickled across Europe and was eventually adapted in major cities across the United States. In 1970, a gay man named David Mancuso who’d been hosting record-playing parties since the mid-60s began hosting invite-only events in his apartment. Part of his goal was to provide a community for gay men to dance and socialize without fear of police violence — what the Stonewall riots had responded to a year before. Crowds flocked to hear his state-of-the-art audio equipment flood the space with rhythmic, soulful music, often with Afro-Latinx roots. Eventually, his apartment was christened The Loft.

As audio engineer Alex Rosner recalled in Bill Brewster’s Last Night a DJ Saved My Life, “[The Loft] was probably about sixty percent Black and seventy percent gay…There was a mix of sexual orientation, races, [and] economic groups. A real mix, where the common denominator was music.”

Mancuso helped DJs pool music for hosting dance parties, and the sound and vibe of his parties spread across New York, getting appropriated by private parties as much as dance clubs. It’s worth noting that, during this time, New York City was not unlike much of Europe after WWII. Infrastructure was weak, crime was high, and the city was verging on bankruptcy. American culture was also nursing a cultural hangover from ’60s idealism. Hip hop and punk are often referenced as disparate responses to shared conditions, but disco should also be seen as a reaction to systemic failures. Who bore the brunt of New York’s social problems? Queer, Black, and Brown communities. Some of them just danced their troubles away.

This is what’s coded into disco music. Listen to some of its most popular tracks: “I Will Survive” is about Gloria Gaynor finding joy and strength despite her most challenging moments, and it became a rallying cry for AIDs activists. Legendary gay group Village People wrote “YMCA“ to celebrate the organization for providing affordable, temporary, single occupancy rooms to people experiencing homelessness. The subtext was, if you’re gay and on the streets, don’t despair: It’s fun to stay at the YMCA. Amii Stewart’s album Knock on Wood and the video supporting its title track are stunning examples of Afrofuturism. Though a cover, Stewart’s version of “Knock on Wood” is the best known one, and it survives as a gay anthem.

In this light, it’s easy to see why numerous musicians and scholars have described Disco Demolition Night as an outpouring of racism, sexism, and homophobia. Footage from that evening shows white people — mostly men — clamoring into the gates, hurling records like frisbees, throwing beer bottles and shoes at ball players, and eventually swarming the field in what was later deemed a riot. Of course, Dahl still pleads the event was harmless fun. Don’t we know white men were losing their place in the world? Working class ones especially didn’t know where to get a suit or how to get into a fancy city club, so can you blame them for lashing out at what, to them, were symbols of that? This, a year before Reagan’s campaign to “Make America Great Again.”

Comiskey Park was located on the Southwest side in a neighborhood called Armour Square, which hugs Bridgeport from the east. The stadium was demolished in 1991, and a new one was built in Bridgeport, eventually renamed Guaranteed Rate Field. Last year, the White Sox commemorated the 40th anniversary of Disco Demolition Night a full month before the original event: Pride month. And last Wednesday, June 3, white vigilantes swarmed the streets of Bridgeport armed with baseball bats, pipes, and two-by-fours, harassing and intimidating people returning from a nearby Black Lives Matter march— all while cops looked on. Scared Bridgeport residents streamed videos of it on social media (and I got frantic texts from friends in the neighborhood).

It’s hard to think about these facts and not hear Dahl’s words echoing. It’s just harmless fun, right? Working class white men aren’t sure of their place in the world.

But it’s also hard not to think about what happened to popular music after Disco Demolition Night. DJ Frankie Knuckles was a frequenter of The Loft, and he transported that sensibility with him when he relocated from the Bronx to Chicago in 1977. Here, he DJed at a spot called the Warehouse, a members-only club that catered to gay, mostly Black men, and he developed a disco-based party sound so popular, it forced the club to suspend its membership policy. In the early ’80s, he opened his own spot, the Power Plant, and used a drum machine to overlay heavy, bare-bones beats across disco tracks. This was the birth of house.

Early house innovator Vince Lawrence was an usher at Disco Demolition Night. He told NPR, “It’s ironic, that while you were blowing up disco records you were helping to create [house music]. … It’s funny how things work out.”

Disco Demolition Night heralded a conservatism that’s ideologically alive but has lessened its influence on pop music. Over time, what really got blown up was the cultural hegemony of straight white male rock. Maybe hetero-capitalist patriarchy is next.